Violence in art is obsolete. Today, what artwork depicting violence still has the power to shock? What purpose does violence in art have when we every day see images of conflict, whether in warfare, domestic or even humorous settings (the schadenfreude of the man falling into an open man-hole)? In ancient Greece violence in art was made somehow graceful, erotic: look at the battles going on in the Parthenon marbles, or even the struggles in the later Pergamon sculptures. Those writhing bodies imbued warfare with an irresistible grace and glory. From the medieval ages and onwards, the depictions of hell and the vices of mankind provided an outlet to the wildest of imaginations, and struck terror into those that saw them; the stick men being noshed by devil-fish in Hieronymous Bosch’s visions of the apocalypse was enough to make any tempted individual throw himself to the floor in a fury of Hail Marys. Goya’s own ‘Saturn devouring one of his sons’ embodies a cathartic exorcism of his own struggles with death, disease and madness: the vigour of brushwork and sheer fury on the painting surface is nothing short of devastating.

A prevailing element of violence in art parallels that of sex in art. It titillates us, showing something taboo yet daring us to hold its gaze: we are somehow primevally drawn to the bloodthirsty, the visions of fellow humans suffering, just like we can’t stop staring at all the tits and arse in Rubens’s depictions of biblical scenes, despite their otherwise worthy intent. You can’t look at Bosch and conclude that it pained him to paint devil monsters and men with flowers sprouting from their sphincters in such loving, graphic detail. It is significant, then, the arrival of Warhol’s electric chairs and suicide series. He exploited and revealed to us with calculating honesty our growing obsession with capital and cash, and with the same cold, unflinching manner his turning newspaper reports of poisonings and car crashes into silk screen prints worth insane money reflected our own bored, conditioned capacity to digest images of horror as easily as adverts and cartoons.

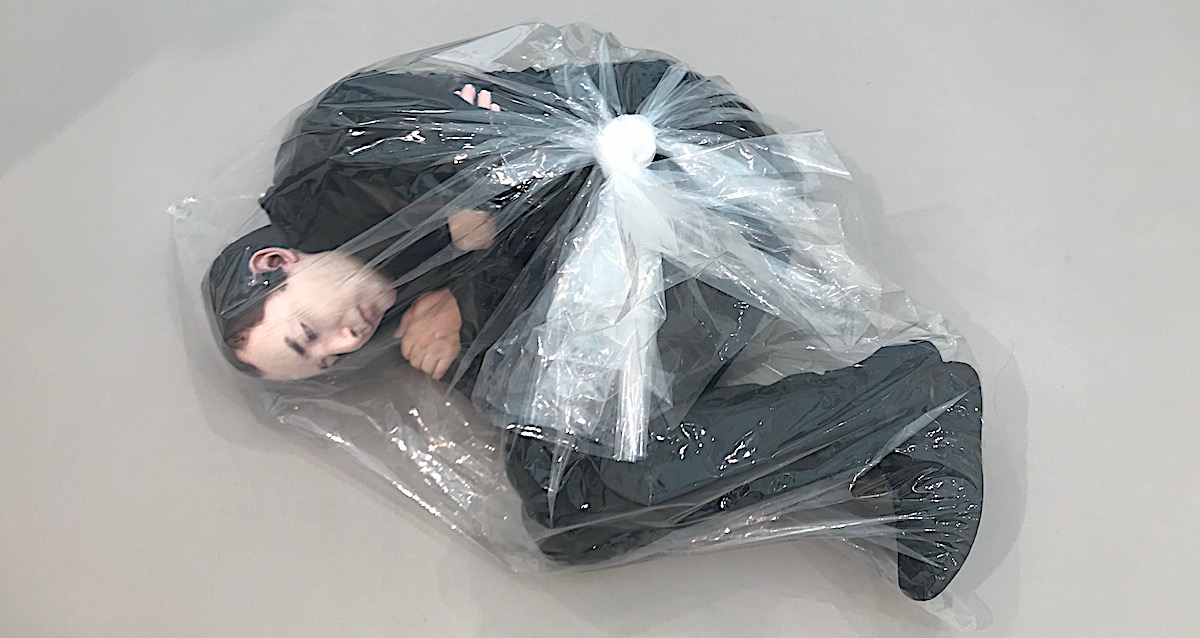

Which is why when Hirst came on the scene with his art supposedly examining life and death, without any real original ideas or opinions that force us to re-examine our lives, we greeted it with a shrug of “oh, it’s like, totally dark”. His cow head in a box attracting flies to their death, or butterflies let loose in a room filled with wet paintings where they stick and die, are one trick gimmicks. So what? With Youtube videos of beheadings and Saddam Hussein being hanged, we are so desensitised to images of death and suffering that artists – when they really want to shock and make a point – are forced to extreme measures, and look silly for it. When Petr Pavlensky nailed his scrotum to Red Square as a protest piece of art, did he ever at any point in his planning think “hang on a second, this is really silly and I’m standing naked in Red Square with my balls out”? We’ve lost our dignity and the capacity to really say something that moves others.

Photo © Artlyst

Bytch@artlyst.com