Hans Haacke is a leading figure in the contemporary art world. His work crosses boundaries of Conceptual, Minimal, Pop and site specific Land Art. He is best known for his investigations into hidden economies and politics including that of the art world and the suppressed histories of people and places.

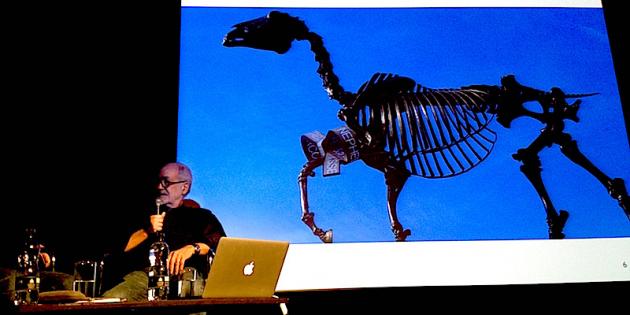

Haacke’s has always had strong political, cultural and social convictions and this is reflected in the nature of his text works installations and sculptures. His controversial approach to subject matter has often landed him in the hot seat with exhibitions cancelled and artworks removed from group shows. The recent unveiling of his ‘Fourth Plinth’ commission ‘Gift Horse’ is no exception to the artist’s reputation to challenge our perceptions of public art. In this weeks Artlyst Conversations Hans Haacke is in discussion with Jon Bird at the ICA. This is part one of two in-depth conversations.

JB Let’s talk about the Gift Horse. Now that is on, How has it met your expectations ?

HH I have to say it is getting more than I expected.

JB In what way?

HH I do not expect that it would get as much of attention as it did and all that respect in the media and I am not use to it (laugh).

JB Can we start by talking about the evolution and development of the project how did it first come about your proposal through to the unveiling a couple days ago?

HH As I have in speaking to the people and try to be sincere. There is a committee that collects name of artists from which they want to invite and they were thirty on this list and from those they apparently chose six from whom they solicited proposals and I was among the six. And I start that almost as a job, I thought ok, let’s have something in because I didn’t expect what it will look in my mind. What I had to look at of course was the history of the square, architecturally but also who is occupying the other plinths. What role these gentlemen played in history that I was not familiar with. And as it is normal, I also made the connection to the present day, what is happening in London but not only in London but in the rest of the world. Then I came up, eventually, with the idea of a squeleton of a horse and looked for a drawing or some visual representations that I could work with in order to supply what the jury expected. And I stumbled on The Anatomy of the Horse, by George Stubbs , it was ideal, and not only because the engraving and book published in the 18th century were superb and also I knew that Stubbs was a favourite British artist because of his portraiture of horses and his legendary depiction of horses. But also one of his famous painting the Whistlejacket is in the National Gallery behind Trafalgar Square. Then, I thought that it was his squeleton and I made adjustments, I can easily do that with photoshop these days. I picked up on a idea that I had realised a few years earlier to introduce a stock exchange ticker in through something that is a totally from a different world. Then it was a question to figure out how could it be realised, but first it has to be accepted of course, and as I said I did not expect that it would be accepted.

JB Interesting talking to a couple of people who are from the selection panel. They said when it came in, when yours came in, everybody in the panel has unanimously agreed this was the one but they had to go to the motions of discussing everything else. This was the one they wanted to go with.

HH I didn’t know to what extent this jury might be at all independent.

After all it is the Mayor who pays for it.

JB Regarding the Mayor’s appropriation of your intentions in the artwork for sort of devious political purposes. I wonder what is your response to it?I guess you anticipated something like that happening ?

HH Well, I could quite imagine how he would react and as I was standing behind him (…). I didn’t quite get everything what he said but I knew it better from reading in the newspapers what he said and I got impression that it was a typical approach and that he provided people with a slight bit of context at some case.

JB In terms of the logistics of it, I mean it is a very big work and I also wondered if you looked at the previous commissions for the fourth plinth. If that was any factor in deciding in things like scale ?

HH Well, of course, I looked at the other occupants of the plinth. And also I have already said the other horses of the square, and George IV and his back. And then in conversation, I learned to be very careful in terms of the size. And so I arrived at the double size of an actual horse which is the size of the other statues.

JB Again I mean the logistics of the ticker tape in moving image. I was struck last night going through Trafalgar Square, how it functions at night time and of course this becomes a very mesmerising object and you are drawn in to this life of ticker tape which is very easy to read at night. On a day to day it is a lot harder because of the sunlight but at night you can read it from some distance. Was that again a fact of what you thought about how would it functions at a different time of the day and at different seasons?

HH Well, I assumed that at certain days or certain lighting conditions it will be easier to see all this. The day light at the moment was the unusual blue sky (laugh) it is not so great but the moment the sun goes down and at night it is perfect.

JB We have got quite a lot of works to go through (…). Reading through and researching for our conversation, I was very conscious of how this is one conversation building on a series of conversations and importance that exchange and communication is to your practise right back to the early work and process work, and your relationship and correspondence with Chris Burden. Then coming through with the October publication right through to most recently is Walter Grasskamp ‘s account of Documenta II. So if we can first on the kind of a larger surface go back to that early moment when your are an assistant as an art student at Documenta II in 1959. I mean to some extent Grasskamp almost implies your are inexperienced and then you were a painter, a painter of abstract paintings of Documenta and observing the behind the scene’s activity, the infrastructure of staging an exhibition. Can you reconnect your experience with that moment?

HH Well, there are important things that I picked up in Documenta in 1959. One was my introduction to a great number of artworks, artists who I might haven’t seen before. It was second time only in Germany that I saw abstract expressionist works also from Europe. It was a fantastic education but I also, as you said, had my first introduction to what was happening behind the scene. It was eye opening as long as I could say, very instructive and for how I looked at the art world later on and participated in it.

JB Did you have a sense that early that maybe this was a subject that at some point would become a focus?

HH No not at all, I was just slightly surprised like a kid.

JB What I have done is that I suggest that we take examples of your work and I have chosen this work which is Condensation Cube from 1963-1964 as an example of your interest in natural system and natural processes and how things, objects, phenomenon respond to external stimuli. Can we talk about the Condensation Cube within relationship with that period of work when this was your major interest?

HH I was very much interested, from the early sixties, in works performed and how they respond to the environment. This one is a classical example of it. It has a minimal art look to it but in effect what happens is that there is indirectly a physical respond to its environment, the changes of temperature and the lighting conditions and so forth. So it is not an independent object as most of works of the past have been. As a matter of fact, people who were in charge of this work were very upset that it would react to the physical environment.

JB I am curious of how you went from being a painter of abstract paintings which have to do with repetition and structure to works like this? What took you out or away from paintings into works that are responsive to the environment. Was it a single sort of event or what is a realisation that the role of the view or the context was fundamentally important?

HH Not a sudden enlightenment. I was very impressed also I eventually met artists from the Zero group who at the moment are getting a new attention. Some of them were involved in how their works are perceived in the physical sense of it. They worked with shadows and reflections and in the early days of the sixties, in effect, their influence would be recognised. These works are optically responsive, where the viewer respond to them in a physically optical manner. And from there, they went on to also mechanical and eventually biological and at the end social interactions.

JB Just to explain if you don’t know this work, it is a plexiglas cube which has a small amount of Water in it and depending on the ambient temperature the condensation starts to occur (…) and particularly the time will make it transparent cube into an opaque cube. Now, the work that I think many people still think about is Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate, which has a tricky history to say the least. It has been shown many times but can we talk through a little bit again about it and the original exhibition that it was attended for and the events that followed from that.

HH On the basis of the works that I have done in the sixties, it was primarily physical works that already incorporated some social issues. Towards the end of the sixties I was invited to have a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim museum in New York. I was friend with a curator there and he introduced my work to do a show and it was accepted by the director.

JB Which is a really big thing for a relatively young artist at that stage!

HH Yeah, it was surprising, of course I wouldn’t fill the entire museum but I would have about 1 or 2 rooms (Laugh). I wanted to continue on the track of social systems (…). I did some research on what New Yorkers speaking about in the minutes when they meet each other like the weather condition and the real estate conditions. I was living down town as most artists were. And then I got interested in who was the largest real estate owner in areas that one could generally refer to as slum areas in New York and opposite to that, the largest private real estate owner of the city in all Manhattan. And I went around photographed all the properties and to the city register office. I collected all the information including the corporations and under what names these are registered, the tax value, and other essential information and wanted to present along as a long strength of images and information at the Guggenheim. Although I wanted to do my first piece and at the time when this was presented to the director Thomas Messer, he thought this was not a work that should be exhibited in a museum and asked me to withdraw it and to replace it with something else or leave it blank. I decided if there is censorship, it should not be a self-censorship. Then it became a bit of a scandal and the exhibition was cancelled. All of a sudden it became an issue of history.

JB Yes, and you were excluded from those major viewing locations for a significant period of time.

HH Well, there was what I am tempted to call a peer group solidarity. American museums did not invite me to do anything on the premises of some argues. Either they were afraid to get into a public agreement with the Guggenheim or they were afraid that I would do something to damage them.

JB You realised that the Gift Horse may have the same effect?

HH I am not betting for another occupation of the plinth in London

JB Looking at your work of that time, sort of photo text work coming out of conceptualism relationship. I would like to know to what extent you were aware that you were part of that period of early conceptual art or whether you felt yourself separated to those kind of developments?

HH I got into the so called social systems at the end of the sixties and this was also the time when the conceptual artists were proactive and became known as outsiders and I knew some of them but I don’t believe that there was much in common. There were many of them maybe Douglas Heubler might have been the closest but as I said I was different to them and occasionally I participating in group shows with them.

JB There is a question about the relationship between the informational and the aesthetics. If you have a project of documenting real estate in Manhattan, the choices you make about how to represent this? the images have the look of social documentary, the text has the look of sort of texts from text books in sociology. The kind of choices you make about how to frame the project, the work?

HH In many cases I try to find a form in the classic term. That is appropriate for one but also appropriate in a way that it should be presented but also picking up, even mimicking, a form in that these things are normally presented to us. So to think of Trafalgar Square, the statues are in the form of other occupants of the plinth. So I just adjusted to that with a slight change.

JB Question around the visual, is this something that is very much in your mind as you are developing ?

HH Very much, therefore I don’t have a recognisable visual style, it changes from one to another.

JB And I am guessing that it needs to be good enough in order to frame the work that you are presenting. I am thinking of those moments when you’ve gone back to the painting that we will show in a second but there is sufficient skill in the representation for it to function as a convincing image but it is not gonna get selected by the BP portrait award for example .

HH It should not look naïf but I am not skilled enough and trained and sometimes obviously plinth occupants could only be produced by people who are skilled to do such things.

JB The next work is Manet-PROJEKT ’74 (related to Manet’s Bunch of Asparagus (1880)). So you are going from process and ecological natural systems and the respond to environment to your interest as you say in social systems and then from that to the art world system. and reconnecting what is traditionally and always been kept separate which is the relationship between the economic structures and the museum aesthetics structures. Again the question is what did lead you to those relationships in these particular works?

HH What you see here is a still life by Manet. This painting was bought and handed over to the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, in Cologne, as a gift, a donation. It was acquired by a collection of German corporations under the guise of the ex chief executive or chairman of the board of the Deutsche Bank Hermann Josef Abs. And in 1974, the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum organised an exhibition, in which I was invited with other people to present a work, to celebrate the museum 150 years anniversary. (…). I knew vaguely who Josef Abs was and I did research on him and found what had been known as a rumour, that he played a significant role in the Deutsche Bank during the Nazi period. He was involved apparently in a number of shady things and also on the board of industries that used concentration camp labour. The work provided the provenance of the painting. I gave the biography of Manet and the next owners. In effect, it was owned at some point by Max Liebermann, the German painter and his daughter inherited the painting and which was brought to New York. They were Jewish. Eventually it came back to Europe. So it was a very peculiar history. Of course I was triggered to do this by the story.

JB – What was the response to it?

HH Sort of the repeat of the Guggenheim story (laugh), the people in Cologne were suprised, the censorship is something in other countries but Germans are also capable of doing that when a banker is involved or even when there is a Nazi aspect to it. It was banned, not exhibited. A very young art gallery, Paul Maenz, in Cologne, accepted to exhibit the work during the time of the exhibition from which I was intended for (…).

JB It seems to follow you in your career….

HH Yes, I am getting used to it!

Professor Jon Bird: is a sculptor an academic and critical/cultural theorist. He co-founded the journal BLOCK (1979-89) and the Block/Tate conferences and publications on visual culture. He has been teaching, writing and curating for nearly three decades and has authored several art books. Most recently, Prof Bird has continued to extend his research on American artists with a range of outputs in preparation for 2015-2016. He has collaborated on the current Serpentine exhibition of Leon Golub. He is also editor and co-author of the book accompanying the exhibition published by Reaktion Books. He is also writing an essay on the early paintings of Golub (1950s-60s) for an exhibition of the Chicago Monster Roster Group to be held at the, University of Chicago, early 2016. Prof Bird was the co-organizer with Dr Luke Skrebowski of the conference on the American artist Hans Haacke on the occasion of the unveiling of his sculpture Gift Horse in Trafalgar Square at London’s ICA, March 2015.

Transcribed by : Sofia Touzani Photo: © Artlyst 2015