In the twenty years since he began a Foundation Course at the Leith School of Art, Alastair Gordon has proved himself to be an artist of distinction as well as a polymath whose activities have supported others in travelling along creative paths. In that period, in addition to exhibiting in California, Edinburgh, London and New York, he has founded and directed a gallery (Husk), co-founded and directed a network (Morphē Arts) of artists, musicians, writers, designers and performers supporting graduates as they transition into professional practice, taught courses at the Leith and Wimbledon Schools of Art, and published a book (‘GodArt’) exploring signs of faith in contemporary art. It is an impressive set of achievements from an artist whose paintings, according to Juan Bolivar, ‘are made with the sophistication of trompe l’oeil and … the naughtiness of a schoolboy who has scratched his name on a school desk to leave his mark on history.’

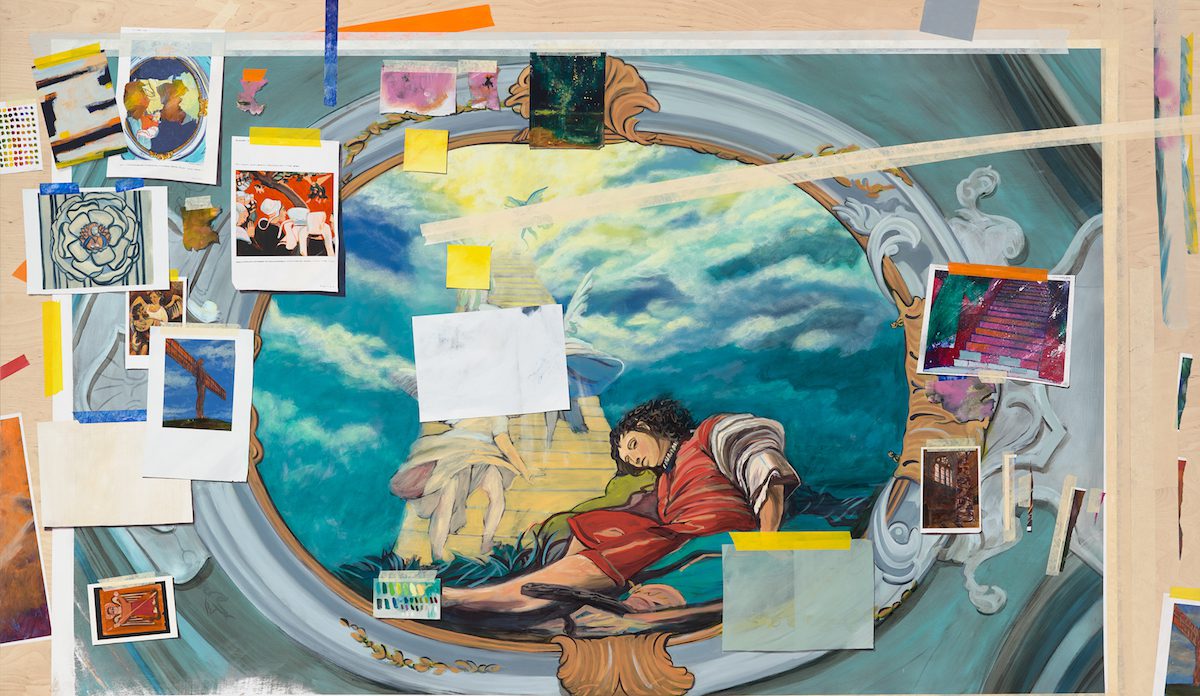

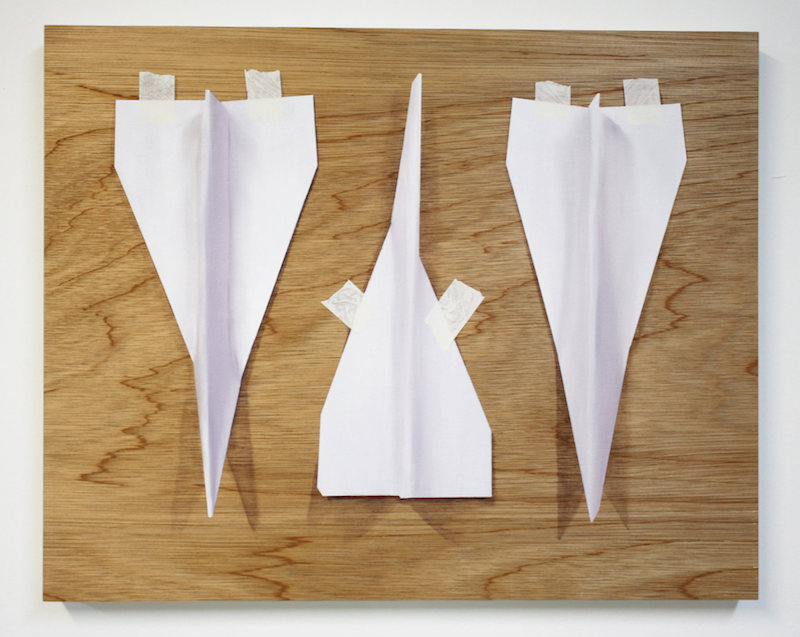

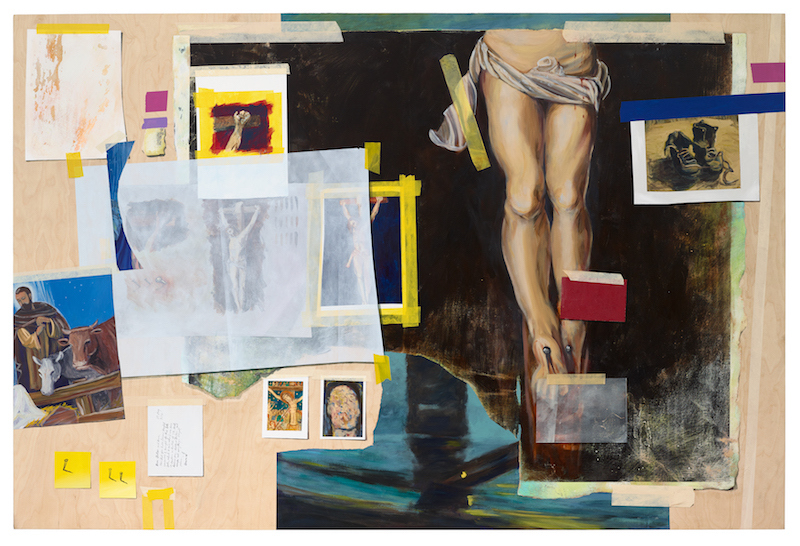

His work can currently be seen at Husk, the Gallery he founded in Limehouse, until 25 July and in the Summer Show at JGM Gallery in Battersea. His paintings are ‘testament to his faith in images to be transformative instruments, underpinned by the story of art.’ His current practice refers to a specific form of illusionism that proliferated in 17th century Northern Europe called quodlibet. They are paintings about paintings: images that oscillate between artefact and artifice, where artists materials such as masking tape and paper are rendered in paint to appear as taped or pinned on a wooden surface. Notions of authenticity lie at the heart of his artistic enquiry raising questions about the replication of the image, craft of the artist and certainty of the viewer.

JE: Your recent work references a tradition of illusionistic painting called quodlibet (what you will) that proliferated in Northern Europe from about 1600. One starting point for your use of this tradition was the history and architecture of Departure and Husk (a creative space in Limehouse), where you were a resident artist and Gallery Director. How did your work in these contexts lead to your engagement with the quodlibet tradition?

AG: I have always been interested in the lesser-known reaches of art history. The quodlibet approach to painting is one of those obscure sub-genres trompe l’oeil illusionism that very few people seem to know about. I stumbled across it while researching for my residency at Departure. Before its conversion to an arts, centre Departure had first served as a seaman’s mission hall. I’d been making paintings of artefacts left behind by the sailors from the centre archive. They were painted in low relief to appear as museum artefacts as if pinned or taped to a wooden surface. Someone suggested they look like quodlibet paintings which I hadn’t heard of at the time. The genre involves painting objects to look as though they’d been thrown down on a table at random or pinned to a wooden wall. They were a form of still life but, to me, they also asked questions about illusionism in painting, about replication and even about death.

JE: Jean Baudrillard wrote in The System of Objects: ‘We are fascinated by what has been created … because the moment of creation cannot be reproduced.’ While the moment of creation cannot be reproduced, the results of creation often can be investigated or reproduced. Scientists can investigate the Big Bang by means of the resulting universe. Paintings exist in their own right following the moment of their creation and can be viewed, debated and reproduced as a result. You create paintings about paintings, reproducing images that refer to histories which are beyond the grasp of the viewer, and therefore would seem to be exploring visually what it is that we can know and how it is that that is known. To what extent do you think of your work as a form of philosophical enquiry?

AG: I think all painting is a form of philosophical enquiry. John Berger described painting as a way of seeing but it’s also a way of thinking or making sense of the world around us. Painting is also a proposition. We respond to the ideas of our times and, for me, this is about the relationships between things made or created, digital or analogue, reproduced or replicated.

My paintings are an attempt to make sense of how artefacts come into being. These questions find their source in philosophy but historically artists (in the west) have more usually referred back to theology. These questions about how things come into being have a wider resonance with how the universe works. I like to reproduce the evidence of the creative process: the masking tape that holds the paper to the board, the splash marks on the studio wall or the residue left over from the painting process As an artist I work with materials like paint, pigment, oil and wood – things made of carbon that already exist in the universe – that I had no say in creating ex nihilo so to speak. Yet I can reassemble them and make something ex-material that no one has ever seen before.

Perhaps Michelangelo was right when he said the sculpture is already there in the marble. The role of the artist is simply to bring it forth.

JE: The notion of authenticity is central to your artistic enquiry. You said that you find yourself looking for evidence of ‘the real thing’ while being aware that the historical veracity of the objects you reproduce is in constant doubt. I’m interested in the extent to which you connect this artistic enquiry to your personal faith, as this enquiry would appear to find its centre in issues of faith and doubt, belief and suspicion.

AG: I am a Christian and I am an artist. As a Christian I hope that my faith would inform every area of my life including my art practice yet I don’t think you would necessarily know I was a Christian just by looking at my painting. In fact, I rarely approach religious motifs or ideas in my work. That is to say, I don’t make paintings about Jesus, the cross or angels etc. Neither do I make paint specifically for a church context or audience. Instead, I am very interested in the idea of contemporary painting. This is the world in which I live, move and have my being. Specifically, I am interested in how paintings function as both an artefact and an artifice: how they are both an object and an image.

As a Christian I am interested in how the world works, that which is true or real and that which is fake. In my painting, I reproduce images that have first been mediated through digital and printing processes. If you will, my painting is an enquiry into how images function today: how the meaning of an image can be replicated, reproduced or disseminated. Indeed, there is a question of the real and hyperreal.

As Alain de Botton writes, ‘Christianity… never leaves us in any doubt about what art is for: it is a medium to remind us of what matters.’ While I wouldn’t describe myself as a Christian artist I am certainly a Christian who is an artist. As such, I hope to continue in this legacy and to keep asking the questions that really matter about why we are here, where we are going to and what good we can serve in the time God has granted us.

JE: You’d never painted biblical scenes until your 2017 exhibition ‘Souvenirs from the Waste Land’, where you drew on the postcard collection of Howard and Roberta Ahmanson, philanthropists and art collectors in L.A. You’ve spoken of this change of direction as ‘causing all kinds of problems’, as you consider how one represents stories or ideas from biblical texts in a way that relates to the history of that tradition in Western painting, but also steps away from that type of visual language in a very contemporary sense. Does this difficulty derive in any way from the extent to which we are distanced from the underlying reality, historic or otherwise, to which these stories relate by the layers of interpretation through which we approach them?

AG: At first the difficulty lay in painting a subject to which I emotionally attached. In my painting I might render an image of a cartoon frog in the same I would a postcard reproduction of a work by Rembrandt. There is an irony here that both images are presented with equal intention. However, when it came to painting Reuben’s crucifixion I found it intensely difficult. How could I paint the crucified Christ in this way? Of course, I wasn’t really painting Christ but rather a postcard reproduction of a painting of Christ. Even still, I found it a deeply troublesome action of my painting.

I agree that we find it harder to relate to the stories of Christ when we become distanced from the underlying reality that binds them historically and contextually. In Ways of Seeing John Berger described how the meaning of an image alters as it becomes reproduced, mediated and recontextualised. We see this in kitsch Christian paintings where the love of Christ is reduced to a sentimental sunset or the majesty of creation to pink fluffy clouds. Yet we live in an image-saturated society where pictures are consumed quickly and constantly reproduced and read in different contexts. This really is at the heart of these new paintings: how the things of eternal value can still be referenced through the transient nature of the thrown-away image.

JE: Like Maggi Hambling, who paints a crucifixion every Good Friday, you have an annual practice of painting an Advent image. These paintings, such as ‘Sacrament’ (2013), explore the way images embody ideas that surpass the mere sum of their parts becoming signs or symbols, pointing towards a deeper value. Is this way of encountering ‘the real’ through accrual of meaning different to the more deconstructive discussion we’ve had so far, or an element within it?

AG: I find it helpful to adopt a rhythm in my painting practice. It’s a simple thing but an annual painting for advent helps me set a tone for the rest of the year and of course to celebrate the season.

Painting is full of contradiction. There can be meaning and discord, reality and illusion, deconstruction and reconstruction, all held together in tension. The sacrament series was an appropriation of the language of sacrament bound within a certain church tradition. At the time I was relating certain ideas from Greenberg’s theories to notions of sacramental art from the Catholic tradition. These ideas at first seemed mutually exclusive but somehow they were held together through the painting.

JE: Your book ‘God Art’ and Morphē, the network of artists, musicians, writers, designers and performers which you lead, both derive from an interest in how faith influences art and how artists approach questions of religion through their art. Both reference a sense that very few, if any, artists were making work in sympathy with religion and religious ideas in the modern and post-modern periods, yet also acknowledge that there is now growing evidence of an under-acknowledged or even untold story of such work. Where do you think we are currently in our understanding of the modern heritage we do actually have of artists making work in sympathy with religion and religious ideas?

AG: My book, ‘God Art’, began as a response to writers, critics and artists such as James Elkins and Dan Fox who had written about the lack of a credible voice for religion in late Modern and contemporary art. I was frustrated by the lack of role models for artists like myself who are sincere in their religious belief but wanting to approach questions of faith in their practice in a way that is thoroughly contemporary, with rigor and in a spirit of open dialogue with those who may see belief in God as something irrelevant, unintelligent or naïve. The more I researched the book the more I encountered artists who shared this concern. Surprisingly, many came from a non-religious background such as Macedonian born Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva or the British artist Michael Landy.

To say there is a return to ideas of faith in contemporary art would be too bold a claim but there certainly seems to be a willingness to ask again what religion has to offer the world. I see an openness to post-secular ideas amongst the artists I work with, yet less so amongst the art critics and art schools. At Morphē our hope is to open a dialogue about the place of faith in contemporary art. We hope to do this in a way that opens up a conversation rather than close things down. Christian institutions aren’t generally known for being open-minded and tolerant so we have our work cut out for us but I hope we can at least raise a few questions about how religion and religious ideas can serve for the good and help human beings to flourish.

JE: How important is it for those that Morphē supports that they should have an awareness that they could, for example, explore the practice of a contemporary artist like Makoto Fujimura or an early modern like Maurice Denis in relation to the making of work in sympathy with religion and religious ideas and of the issues that those artists face or faced in doing so?

AG: It’s of the utmost important that Christians in the arts know the legacy of those who have gone before them and who their peers are at the moment. Fujimura is less known in the UK and European contemporary art markets than he is in the US. Likewise, I don’t know many contemporary artists who would site Denis as a key influence, yet his painting and illustration (not to say his writing) are important in understanding the shift from late Impressionism to early Modernism. There is scope, even necessity, for a more robust understanding of art history amongst art graduates. When I was an art student myself we were rarely encouraged to look to art history for ideas or inspiration. Instead, we were encouraged to read philosophy. Yet art and philosophy have always enjoyed a cohabitation.

In Morphē we run monthly book groups where art history and philosophy is read and discussed. The idea is that we can build on the legacies of the past and get a better grasp on why artists of faith often feel ostracised today from the wider corpus of contemporary art.

JE: Morphē supports graduates as they transition into professional practice by offering free mentoring and hosting events. To what extent does Morphē build on, develop or complement the mentoring of graduates that has been offered by other organisations such as the Arts Centre Group?

AG: The ACG were a big influence on us when we started. We still work with them on shared projects such as the group exhibition at St Stephen’s last year. There have been several groups like the ACG who have helped us an inspired us along the way, not least the l’Abri Christian Fellowship and the Artisan network. Our programme may be a little different in that we really champion a rigorous understanding of contemporary art theory and critical discourse. This seen through the lens of the bible and the Christian tradition. I’m very grateful for the work of the ACG and hope we can continue some of the things they set out to do nearly 50 years ago.

JE: As an art student, it was the writings of Hans Rookmaaker and Francis Schaeffer that first helped you to think about how art and Christianity connected. In ‘GodArt’ you state that you owe them a great debt of gratitude, while also exploring other ways of envisaging these connections. What do you take with you from these writers and what might you leave behind?

AG: Ooh now that’s a question! Perhaps one for a book in itself and here I would default to my friend Jonathan Anderson and the book he co-authored with William Dyrness, Modern Art and the Life of a Culture. Yet, in short, it was the writing of Schaeffer and Rookmaaker in particular that first helped me to connect my faith in Christ to my painting. I read Rookmaaker as an art student. At the time I was somewhat on the brink of giving up on Christian belief and it was his writing that showed me the possibility of thinking credibly about Christianity whilst thinking Christianly about art. Although strangely it was his writing about Jazz that I found more compelling.

What did I take from Rookmaaker? If nothing else, an urgency to research the subject of art that I loved so passionately. Not just to sense my way around it or to paint whatever I felt but to think about how my work could respond to the ideas of my time and moment in painting.

What to leave behind? I’m not sure I agree with the way Rookmaaker reduced some late Modern artists to be either absurd or normal. To my reading, he would often make sweeping statements about artists, at times quite damning, that perhaps could have benefited from a greater measure or critical response from others in his field.

JE: In ‘God Art’ you write about the work of Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva and Michael Landy as seeming to represent a new category of religion-based art. Their work doesn’t appear to be about religion per se nor is it out to convert you but it seems fuelled by a genuine naivety or curiosity towards religious ideas that ultimately becomes expressed in a manner sympathetic to questions of faith. What conversations or avenues of exploration do you think this new category of religion-based art could open up and where do you see your practice in relation to it?

AG: Here I think it’s helpful to talk about specific works rather than wider intentions of these artists. Of course Elpida Hadzi-Vasileva and Landy make other works that don’t specifically approach questions of religious belief. Yet I was especially struck by the sensitivity of Hadzi-Vasileva in her work for the Pavilion of the Holy See at the Venice Biennale. Here she responded to a text from John 1 about the Word made flesh. The work demonstrated a remarkable theological insight and energy that one rarely sees even in a work made by a Christian. It seemed at once curious and winsome; sincere yet whimsical. I think artists who grow up in a Christian tradition can often feel a burden to make art that is biblically ‘sound’ or correct. Perhaps they feel a need to preach or align. Rarely does one see an artist who simply plays with Christian ideas yet without cynicism? These works by Hadzi-Vasileva, as well as Landy’s Saints Alive, demonstrate an exploration of Christian ideology almost through the eyes of a child – as if seeing for the first time – yet with the rigour and nuance, you would expect from a credible contemporary artist.

Interview: Revd Jonathan Evens © Artlyst 2018