Art history generally lauds the arrival of democracy in Greece in the 5th Century BC, accompanied by a similarly noble pinnacle of super-naturalism in sculpture; that is, a form of art generally received as characteristically ‘pure’, or ‘above nature’. The arrival of the rule of law signified the backbone upon which democracy continues to structure itself.

It is disturbing then that the imminent high court ruling will decide whether the publishing of Prince Charles’s so-called ‘black spider memos’ are within the public interest. For it is the current publishing ban which effectively protects Prince Charles from adhering to democratic policy in the arts sector. While the Queen remains impartial and inert, that the Prince’s active lobbying – regardless of content – is kept out of the public domain is at odds with the transparency which facilitates democratic process.

Why did we bother passing the 2000 Freedom of Information Act in the first place if certain individuals within the political process remain exempt? That the secret content comes from an outspoken supporter of homeopathic remedy, whose previous constructive criticism of progressive architecture was spoken with typical sledgehammer subtlety as a ‘carbuncle on the face of an old friend’, provides further cause for concern. Once made ultimate authority – a king, and unchecked – it is not difficult to find precedent for the eventuality that may come about in other cultures where freedom of expression is dictated by powers on high.

On a sillier note, you can enjoy frivolous art that poses no intellectual threat to anybody in the form of Mexican squillionaire Pérez Simón’s vast collection of first rate Victoriana at Leighton House. The opulent setting is Frederic Leighton’s late 19th Century self-congratulatory ode to exotic excess (check out the staggeringly brilliant Arab Hall of 1877-81 which in typical Victorian stuffiness strives to out-Arab Turkish decorative design), providing a perfect marriage of painting and setting.

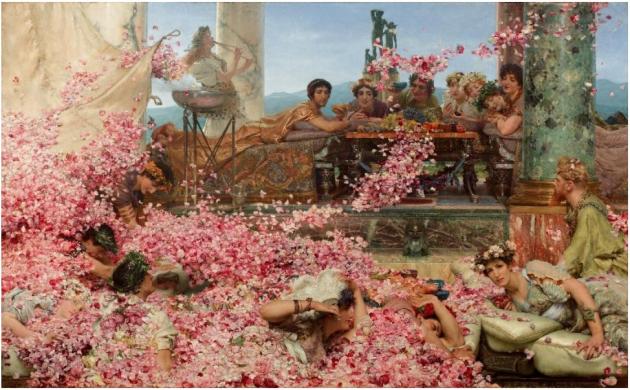

It’s worth seeing alone for the sheer volume of consistently stunning technical painting, bearing little philosophical content other than nude babes in distress with vaguely gormless expressions, and also worth seeing because this is the only chance this lifetime of catching a glimpse of these important works before they disappear back into his bathroom or wherever. Acquired in 1993 and not seen in Britain since 1913, the staggering technical tour de force that is Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s ‘The Roses of Heliogabalus’ gets its own room, though I would have enjoyed being able to gaze at it while lounging in my pants eating pizza as Pérez Simón has the luxury of doing if he wishes.

Instead, we’re treated to that rare curatorial gimmick: the stab at recreating synaesthesia by filling the room with an overpowering rose fragrance. Certainly attempts at creating mood have had more success when, say, musical – note the National Gallery’s cute accompanying of ‘Vermeer and Music’ with chamber orchestras – but here it detracts from, rather than enhances, the visual technicality of the piece. Plus if it catches on, visitors may shortly be enjoying the delightful aromas of eau de rotting flesh to fully enhance the experience of Géricault’s ‘Raft of the Medusa’, or unwashed lady knickers for Courbet’s ‘L’Origine du Monde’. Tasty.

By The ArtBytch