When NASA circulated the first documentary and scientific photographs taken from space to the public in the 1960s they brought the alien and distant into stark proximity with the mundane. With Earthrise (1968), Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders captured the emotional impact of the Space Race: allowing us to reflect on the beauty, frailty and unicity of our planet Earth and our place within the universe.

Today, as telescopes and spacecraft send back images which are arguably just as powerful in their aesthetic impact as in their scientific content, it is perhaps artists who are best equipped to interpret what these dispatches tell us about humanity’s relationship to a cosmos in which we seem ever smaller and less significant. In dark frame / deep field, six contemporary artists explore the limits of our ability to image, map and define the universe, with artworks displayed alongside vintage photographs from NASA that first brought the breath-taking scale of outer space into view.

Two works by Caroline Corbasson span the entire history of telescopic exploration conceptually, referencing Galileo’s revolutionary drawings of the Moon from 1609 as well as the 13 billion-light-year compression of 2005’s Hubble Ultra Deep Field. Her large-scale Crater (2013) inevitably conjures up early observational sketches of the lunar surface, as well as more recent photographic moonscapes, but is in fact a depiction of a 50,000 year-old impact feature in Arizona. Meanwhile, with a meticulous layering of star maps in Naked Eye (2014), Corbasson seems to transform the flat cartography of the sky into a three-dimensional simulation of the entire universe.

In his Blackout series (2010), Dan Holdsworth presents the Earth itself as an alien object, turning an astronomical eye back towards our own planet. Holdsworth defies perceptions by reversing negative / positive values, morphing the sooty ice of the Icelandic Sólheimajökull glacier into a spectral veil set against the inscrutable darkness of the northern sky. Barren and supernatural, the transmuted geology recalls the digital data beamed back by probes that have mapped the terrains of Venus, our solar system’s moons and asteroids.

Astronomical photographs record time as well as space: not only do they compress a duration of seconds, minutes or hours into a single exposure, they also capture light that has been travelling towards us for years, decades or millennia. Philippe Pleasants’ poetic skyscapes (2010-11) condense the passage of time as marked out by the motion of the Moon, Sun and stars. In his solar and lunar durations the temporal element is spatially anchored in specific English landscapes, but in Trace 3 and 4, the sky’s motions are stripped of all earthly references to become an abstract grid of curving lines.

With Objects in the Field (2013) and the Observation series (1991/2013), the result of a collaboration with Dr Roderick Willstrop from the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Sophy Rickett unearths the archaeology of astronomy itself. Rickett’s work juxtaposes deep time with history on a human scale by resurrecting astronomical photographs which, although they are only a few decades old, are already technologically obsolete.

Displaying their characteristic playfulness, We Colonised the Moon (Sue Corke and Hagen Betzwieser) reveal the political implication of Neil Armstrong’s ‘small step’, when the Moon irrevocably became a place, rather than a distant light in the sky. In bold, ‘pop’ colours, the silkscreen prints Frigoris and Tranquillitatis (2012) re-appropriate lunar cartographic data from the US Geological Survey to query humanity’s claims on Earth’s satellite. Using the ‘high-brow’ rhetoric of traditional museum display, As Good as a Moonrock (2012) questions conventional methods of classification and the authenticity of lunar exploration.

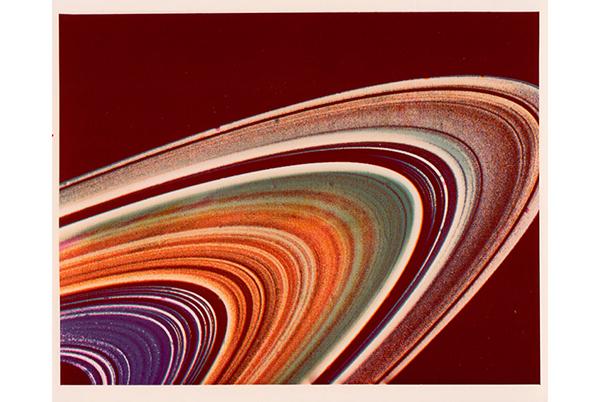

By juxtaposing early space photographs – whose value at the time was as much about public relations as it was about science – with creative responses from today’s more cynical world, dark frame / deep field demonstrates a maturing engagement with the sublime spectacle beyond our world’s atmosphere. At the time harbingers of the future, vintage NASA photographs have the graininess and faded colours of holiday snaps of the same period, giving them an aura of nostalgia and optimism. But our frontiers never cease to expand. On 14 July 2015, NASA’s New Horizons probe will rendez-vous with Pluto after a ten year voyage, bringing another world into sharp focus for the first time. In the seventeenth century it was the beauty of Galileo’s drawings which brought home the full revolutionary import of his discoveries. In the twenty-first century, as technological advances give us access to ever more dizzying and humbling astronomical vistas, art is once more playing a vital role in conveying the meaning and implications of cosmic exploration.

dark frame / deep field is curated by Marek Kukula, astronomer, writer and broadcaster and Melanie Vandenbrouck, curator and art historian.

The show coincides with the arrival of the NASA space probe New Horizons at Pluto on 14 July 2015.