There can be no doubt that the Turner Prize is pretty much of a sick puppy right now. Supposedly Britain’s premier award for new art, it is defined as being either for ‘an artist working primarily in Britain,’ or for ‘a British artist working anywhere’.

It seems now that the Turner has never reached this level of excitement or possible relevance since it peaked at the end of the 1990s – ELS

It has gone through a number of metamorphoses since its first incarnation in 1984. On that occasion the surprise winner was Malcolm Morley, who died in June this year, aged 86. Though he was born in Britain, he never really formed part of the British art world. After a troubled childhood and youth, he studied at the Royal College of Art, where Peter Blake and Frank Auerbach were among his fellow students, then moved to live and work in the United States. There he became a successful painter, associated with the Photorealist movement, but was never regarded as being a figure of absolutely the first rank. The three runners-up for the first edition of the prize were then and are still better known here in Britain: Richard Deacon, Gilbert and George and Richard Long. By choosing Morley, the jurors made a rather clumsy statement about their wish to attract international, not merely British, attention to the prize. It has never been really successful in doing this, throughout all the years since then.

During the rest of the 1980s, the Turner seemed content to operate on the well-established British principle of Buggins’s Turn. There were no surprises, just a procession of safe, well-known names: Howard Hodgkin (1985), Gilbert & George (1986), Richard Deacon (1987), Tony Cragg (1988), Richard Long (1989). The same artists tended to recur in the annual shortlists. If you were listed and didn’t get it, but nevertheless belonged to a certain establishment-approved category, you had a quite good chance of succeeding next time around. The shortlists meanwhile grew ever longer. There were four contenders in 1984, eight in 1988, and seven in 1989.

The organisers by then recognised that it wasn’t stirring the excitement they hoped for. In 1990 there was a hiatus. The Turner took a gap year. When it came back it was a very different beast. The shortlists were restricted to for names only, and the listed contenders had to be under 50 years of age. This last requirement was abruptly dropped last year, in order to give the prize to Lubaina Himid, who is in her sixties.

The revived Turner came back at just the right moment to publicise a new wave of British artists, the so-called YBAs – Younger British Artists. And there were other interesting contenders as well. Anish Kapoor win in 1991, Rachel Whiteread won in 1993, Antony Gormley won in 1994. And the Great Damien – Hirst, who else? – was the laureate in 1995.

Some of the YBAs who were shortlisted, but who didn’t, in fact, win, nevertheless benefited hugely from the publicity, and of course from the controversy, that their work aroused. In 1999 Tracey Emin’s installation My Bed, proudly emblematic of a sordid lifestyle – ‘Look at me, what a BAD girl I am!’ – got huge exposure in the tabloid press. Her work was prissily condemned by then Culture Secretary Chris Smith but was also largely responsible for carrying attendances to the show to a record 140,000, with an average of 2000 visitors a day. Patron Charles Saatchi bought the bed for £150,000 and installed it in a special room in his house. When he decided to sell in 2014, it made a little over £2.5 million at public auction.

It seems now that the Turner has never reached this level of excitement or possible relevance since it peaked at the end of the 1990s. It’s worth asking oneself how did it all go wrong?

Partly, I think, it’s not the fault of the organisers. The art world has changed, both in Britain and elsewhere. In particular, the YBAs, now middle-aged, have found no successor group. Certainly, none that has attracted official patronage of the kind offered by the Turner Prize in the 1990s.

Avant-garde groups, on the pattern established at the beginning of the 20th century by the pioneer Modernists, have pretty much vanished from the entire international scene. In Britain, ironically enough, the nearest recent equivalents have been the Stuckists, who, from the end of the 1990s onwards, have been a guerrilla movement opposed to Establishment patronage of ossified avant-gardism. The notion of a retro avant-garde, if one may call it that, is not in itself entirely new. The long-ago Pre-Raphaelites, of the first half of the 19th century, represented a similar impulse.

The Stuckists, while retro in spirit, have been savvy about using new developments in technology, particularly the outreach offered by the worldwide Web, to publicise themselves. They are no longer dependent on official patronage to make themselves known. The website stuckism.com currently claims that there are 236 Stuckist groups in 52 countries. Stuckism is an undoubtedly British product, an art movement that originated here. The influence of the YBAs never stretched as far internationally as the still continuing influence of the Stuckists, nor did it last so long.

The British Stuckists used to demonstrate outside Tate Britain at the time of the annual Turner Prize exhibitions, but they have long ago given up doing that, claiming it is not worth their trouble. One can see their point.

There is also another practical reason for the absence of these manifestations, which is that the Turner shows are no longer held solely in London. Since 2011 the exhibition has alternated between London and locations in various provincial cities: Newcastle in 2011, Derry in 2013, Glasgow in 2015, Hull in 2017. In 2019 the exhibition will be in Margate. These are well-meant gestures, but they have produced a noticeable drop off in publicity and, I suspect, a drop off in attendances. A Turner Prize show in Margate is unlikely to attract 140,000 visitors, much as the location may soothe the democratic conscience of the organisers, and indeed despite the fact that Dame Tracey herself is now based there. The result has been a two-tier pattern. The biennial London shows count for more, in terms of prestige and impact than the London ones.

Another problem has been what is happening in art itself. In particular, there is our fascination with art that that asserts its claim to originality by not being original at all. Except, just maybe, through choice of location. An example of this was Mark Wallinger’s installation State Britain, which won the Turner Prize in 2007. State Britain was a meticulous reconstruction of the Peace Camp set up in Parliament Square by the anti-war activist Brian Haw. In its original form, this existed from 2001 to 2006, when it was demolished by the police.

In its new location, grandiosely sheltered by Tate Britain, State Britain offered a striking instance of preaching to the converted, which has now become the default position of much supposedly avant-garde art.

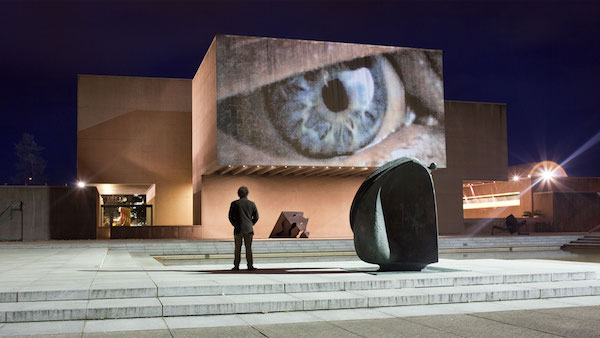

Recently the Turner prize has tended to become more and more self-conscious about the purity of its own intentions, and careful to stress how anti-commercial it is. Its preferred forms have been the ones most clearly resistant to any kind of commercial taint – performance, ad hoc installations, video.

One notes, among the prize-winners honoured in the last decade or so, the lack of any names that have become really familiar as a result, either in international or in purely national terms.

A factor has been a tendency to embrace, not creative individuals, but groups representing worthy causes that have something to do, in the broadest sense, with art. This began with the short-listing in 2010, of an organisation called The Otolith Group. This presents itself on its website as follows: ‘The Otolith Group is an award-winning artist-led collective and organisation founded by Anajlika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun in 2002 that integrates film a video making, artists writing, workshops, exhibition curation, publication and developing public platforms for the close readings of the image in contemporary society.’

If this explanation leaves you feeling a little baffled, as it does me, then there’s a paperback book available on Amazon entitled A Long Time Between Suns, priced at £110.

The Otolith Group didn’t win the main prize, but in 2015 a group called Assemble did. This was greeted with hosannas by Adrian Searle in The Guardian. I can’t do better than to quote him at some length: ‘Assemble’s win signifies a larger move away from the gallery into public space that is becoming ever more privatised. It shows a revulsion for the excesses of the art market, and a turn away from the creation of objects for that market. Their structure that was on show at this year’s Turner exhibition must be seen not as a work, but as a model of work that takes place elsewhere; not in the art world, but the world itself.

For the exhibition, recreated a full-size, wooden mockup of one of the houses in Granby in south Liverpool they have been refurbishing with locals. They filled it with the ceramics, fireplace surrounds, stools, door handles and furnishings they and the residents have been making both to use in the houses and to sell in order to generate income. The overall aesthetic was stripped-down and clean, without being conspicuously forced or arty.’

Their work, Searle says: ‘is a welcome, and vital, part of a bigger battle against social division under the Tories.’

In other words, ‘Please Mr Turner Prize, give me anything but art.’

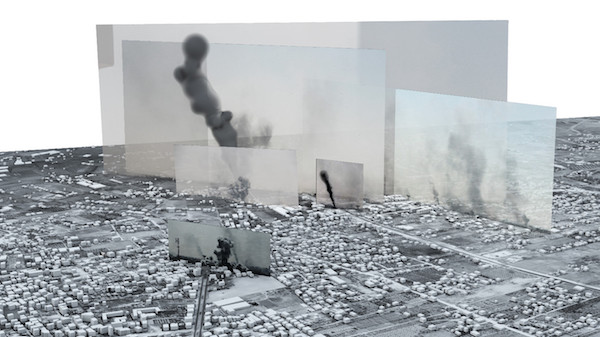

This year the obvious shoo-in for the prize in yet another group: Forensic Architecture. The other three contenders are all makers of politically correct videos. On their website the group describes itself as follows: ‘Forensic Architecture is an independent research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London. Our interdisciplinary team of investigators includes architects, scholars, artists, filmmakers, software developers, investigative journalist, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists. Our evidence is presented in political and legal forums, truth commissions, courts, and human rights reports. We also undertake historical and theoretical examinations of the history and present status of forensic practices in articulating notions of public truth.’

From statements made when this year’s Turner Prize shortlist was announced, the head of Forensic Architecture seemed a little bewildered to find his organisation listed for an art prize. He clearly thought that art was not in fact what they do. But if they win, they’ll no doubt take the money and run. Who could blame them for that?

Meanwhile, where are all the baby artists waving hatchets, dying to punish the current visual arts establishment for its soporific complacency and dimness? Art doesn’t stop happening because the bureaucracy that supposedly runs it has run off and drunk the Kool Aid.

Top Photo: Maria Balshaw Congratulating Lubaina Himid on her Turner Prize win PC Robinson © Artlyst 2017