The British art world is apparently in a healthy state at the moment. In particular, it is on extremely cuddly terms with a benevolent arts bureaucracy. Tate Modern has quite recently more or less doubled in size. There are a number of other major official and semi-official galleries in London that endeavour to bring the latest developments in art before an appreciative public: Tate Britain, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, the Barbican Art Gallery, the Royal Academy, the two Serpentine Galleries, The ICA, Courtauld, NPG, the Camden Arts Centre – this doesn’t exhaust the list. You could wear out a lot of shoe-leather, running dutifully from one to another. The Hayward Gallery, conveniently located on the South Bank, is about to re-open, splendidly rehabilitated.

Strenuous official efforts are made to make sure that the out-of-London audience isn’t deprived. Tate has other galleries in Liverpool and St. Ives. The Turner Prize, Britain’s most prestigious award for contemporary artists, now alternates between London and various provincial centres. In 2017 the prize exhibition, just coming to a close as I write this, was held at the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull. The prize was won by a female artist from a minority ethnic community, born in Zanzibar, who, as the official announcement from Tate tells one, ‘makes paintings, prints, drawings and installations which celebrate Black creativity and the people of the African diaspora while challenging institutional invisibility.’ That’s a lot of desirable boxes, all ticked in one go.

Everything now ought to be for the best, in the best of all possible worlds. Except, of course, they aren’t

There are conspicuous problems here. One is that, while there is an ever more self-congratulatory babble in Britain about ‘emerging artists’, those who ‘emerge’ are no longer young. Reliably ancient would be a more accurate description. If you look at the three most recent big success stories, all belong to artists of indisputable talent. None is anything even remotely resembling a spring chicken. Lubaina Himid, winner of the Turner Prize, is 63. Phyllida Barlow, British representative at the recent Venice Biennale, is 73. Rose Wylie, who made the biggest bang of any solo exhibition in London this year, with her show at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery, is 83. She emerged – that verb again – after a string of late-life successes that began in 2009, when she was one of seven finalists for the Threadneedle prize and became fully established when she won the John Moores Painting Prize in 2014.

Don’t get me wrong – all of these three are artists of excellent quality (would that I could say the same for some of the other contenders for the 2017 Turner). It is also high time that women artists received a much greater degree of recognition than has been given them till very recently. Their success raises the game for other members of their gender. But none of them seems in the least degree likely to change the direction of art. No female Picasso to be found here. No equivalent of the major inter-war Surrealists or post-World War II practitioners of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and Art Brut.

In fact, it is extremely unlikely that they will, either collectively or separately, have anything like the impact that the YBA group had here in Britain in the 1990s. That impulse, where it survives, seems to be guttering out. Damien Hirst, the YBA movement’s most prominent survivor, did indeed successfully upstage the official offerings at the 2017 Biennale, with his double-headed show in two major spaces entitled Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable.

Andrew Russeth, Co-Executive Editor of Art News, excoriated it on the web: ‘Damien Hirst’s doubleheader in Venice is undoubtedly one of the worst exhibitions of contemporary art staged in the past decade. It is devoid of ideas, aesthetically bland, and ultimately snooze-inducing—which, one has to concede, is a kind of achievement for a show with work that has taken ten years and untold millions of dollars to create.’

Other people, including myself, rather liked it, not least for its absence of self-righteousness and cheerful acceptance of the fact that in contemporary society art is often ‘Come with the cash, darling – in our world art is big business.’ Well, that was pretty much the case in Rubens’ day too.

If fact, it must be said that the general tone of the British art world right now bears a startling resemblance to the moralistic atmosphere that engulfed the world of the Victorians. Too many ‘snowflakes’ looking round for a fresh opportunity to take offence. Too many panjandrums and bureaucrats ready to applaud art, however limp and unoriginal in itself that makes propaganda for fully certified ‘good causes’.

Art of this sort doesn’t change the world. All it tends to do is confirm an existing corpus of beliefs. People nowadays go to official galleries as they used to go to church. Too often it seems as if the job of what they present is to supply comfort to the cosseted and complacent, not in any way to change what they think. Yet art galleries, even official ones, can, through what they present and how they present it, bring about shifts of perception – changes in how we see the world outside the gallery.

There are, however, much more directly efficient ways of disseminating political messages. Get up on a soap-box and do it in the street. And let the audience you find there throw lumps of shit at you if that’s what they want. If you don’t like the shit, but can put up with a few hard words, do it on the web.

Meanwhile, let’s hope that somewhere, hidden away, but ready to emerge with a bang, there’s an irritated regiment of artists, under 30 years old, all genders, all ethnicities, ready toc tell us: ‘OK folks – what we want to do is more profound than the politics. We’re going to try to make you look at the world around you in a fresher, newer way.’

Right now, they are not present. Anyway, not here in Britain.

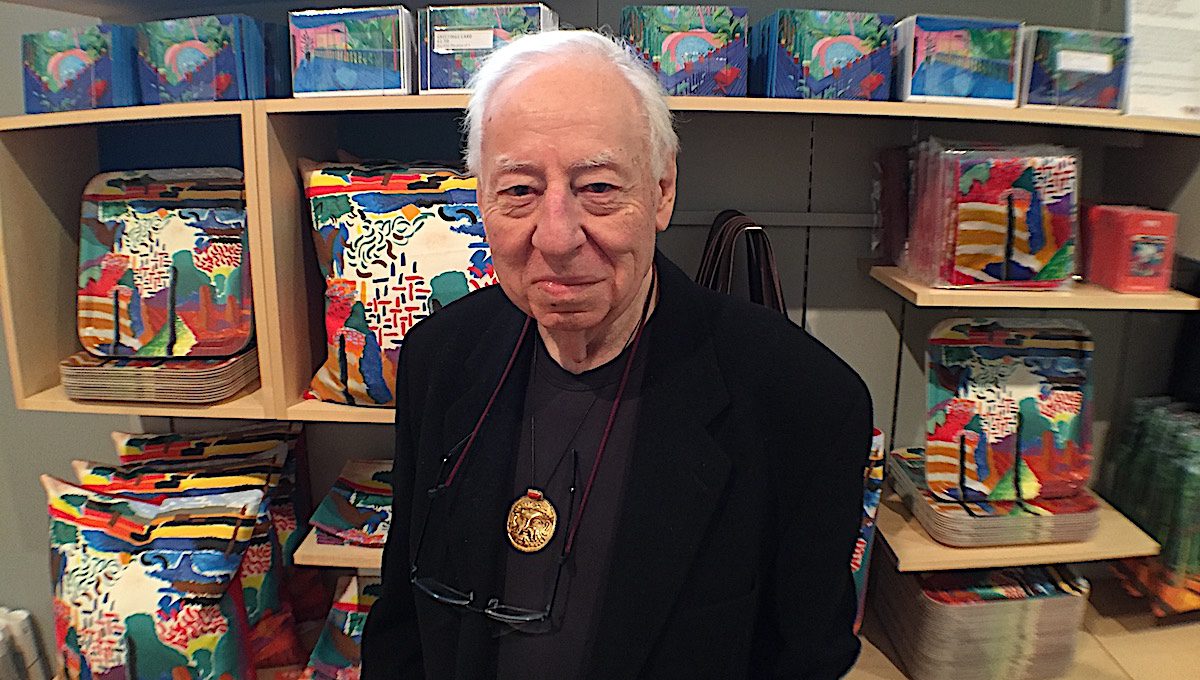

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2017