”The glory of art is to glorify beauty” – Alphonse Mucha

I was very excited to see this exhibition. As a young girl, I was always fascinated by these images of graceful art nouveau women. Mucha’s friendship with the actress Sarah Bernhardt was one of respect, creativity and beauty. In 1895 Mucha lived in Paris. Sarah Bernhardt was at the time a successful star. Her connection with Mucha began with his poster design of her as Gismonda. She was thrilled with the image, and over the years he produced further posters of her which contributed to her success as an actress. Instead of showing realistic imagery, he chose to focus on her inner psyche that captured her spirit and beauty. He approached his work in this way even though he had models posing from life.

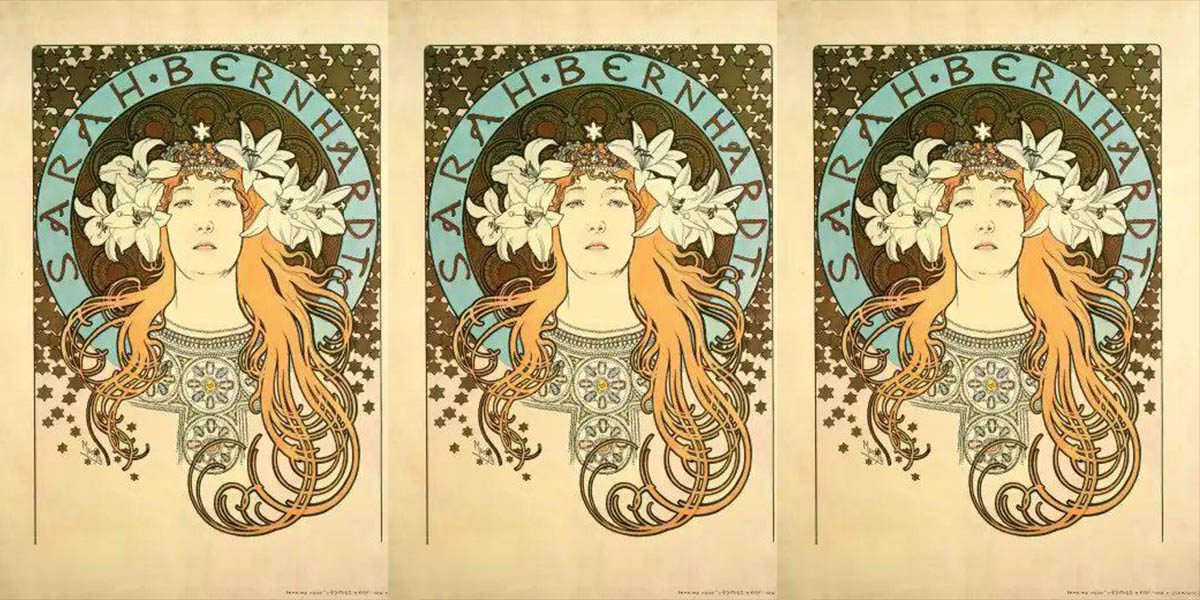

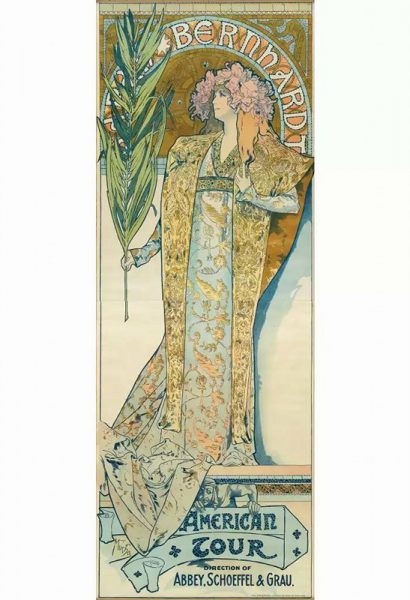

Sarah Bernhardt was one of the most influential figures in Mucha’s life. She was an international star, and in 1894, she contacted Lamerca’s print studio for a poster design for Gismonda, but Lamercia asked Mucha who worked there to carry out this commission. The poster was an immediate success, and overnight Mucha became famous, and his works became objects of desire for collectors. They were long slim posters of dignity and sobriety. The long female form, the halo, the distinctive font created a brand. He focused on the most important attributes of her character and understood Sarah Bernhardt as a great artist and friend.

The exhibition begins with ‘Head of Sarah Bernhardt’, study for Lorenzaccio, 1896 a beautiful drawing which shows Mucha’s expertise and technical drawing skills. He caught her theatrical expressions and admired her classical nobility.

The long feminine artworks are also designs; the beautiful colours and lettering. There is something very graceful, decorative and joyous about Mucha’s works. The lines sweep about gracefully, intermingling with flowers, pattern and intricate detail and motifs, all subtlety composed. This is fine art and graphics combined but also advertising. I thought of Andy Warhol and Lichtenstein and the way in which popular culture and advertising have woven into artists’ works over the centuries. Mucha’s poster effect is eye-catching and lush. There is a sense of music, decadence, quiet dignity focusing on the inner quietude, intelligence and beauty of the female form.

I am standing in front of ‘Gismonda’, Colour lithograph, 1894. Alphonse Mucha is linked with the movement of art nouveau. The Alphonse Mucha Foundation in Prague has contributed these works to the Walker Art Gallery. Do go and see this exhibition of original artworks by Mucha. You still have time to see it as the exhibition is on until 29th October. This is a fascinating and beautifully curated exhibition. The tour guide was also extremely knowledgeable and like the guides at Tate Liverpool, taught us many important historical facts and intricate points of interest.

In Quest of Beauty’ is a touring exhibition and has been exhibited at various galleries around the UK.

The Walker also has a fascinating collection of Rodin sculptures which are part of this exhibition. Mucha and Rodin were also good friends. This exhibition highlights their friendship and the connection they had as well as Mucha’s other friendships with groundbreaking artists of the time such as Gauguin, focusing on Mucha’s early and later works, where the style medium and theme change in later years. There is also a sculpture by Mucha exhibited beside the sculptures of Rodin.

Mucha’s cultural heritage in 1860 was very important to him. He was Czech and born within the Austrian Empire. As a boy, he sang in several large cathedrals in his homeland. He was inspired by the ceremonial rituals, the smells and the design and later he went to Vienna to be a theatre designer where he learnt about theatrical design and decor in inspiring Vienna, reflecting on his inspiration from set design and how this intertwined with his work.

We tend to associate Mucha with posters and design. This exhibition will show you the great artist Mucha as an artist and observer.He wanted to be an artist. Even though he was rejected by the Prague academy of art at the age of seventeen, this did not put him off. He continued with his passion for art despite being discouraged. He travelled around doing general art commissions and then In 1887 he received funding to go to Paris, and in the early 1890s, he began as a graphic designer in Paris. His breakthrough came with his commission from Sarah Bernhardt. They called her the Divine Sarah. She was an amazing and talented actress and way ahead of her time. She used photography to market and push her image. This was unusual at the time. She was brave and eccentric, experimental and daring. She even had a photo taken of herself inside a coffin during times when women did not even have the right to vote. 1894 was the fated day that Mucha was accepted for the job. He had seen her play. He had an idea of what the play was about. The artwork ‘Gismonda’ is a beautiful image. It is a commercial piece of art, never meant to go in a gallery. However, there was something different. It was elongated. The colours were muted. The tones, blues and tans were a similar tone throughout the image. Nothing leaps out at you. Sarah loved this image. She immediately commissions Mucha to design more posters of her plays. It is a beautiful poster but also a beautiful piece of art, Byzantine mosaic, inspired by design of his own heritage. Mucha has put her on a pedestal. She is so famous you don’t need to see her full name. She fills much of the frame. There is this Goddess element to the artwork. It’s powerful and dignified. It has a religious feel to it. It also proved that Poster art could be real art also.

Most of the works are lithographs. Lithography was essentially invented in the 18th century, printers banging out hundreds of commercial images. In the day this was done on a lime stone. It involved oil-based ink and a printing press. You did not get one immediate print. You lay each colour on top of each other. In the Mucha Foundation, you see the lime stones, each with an image carved into it. (Do go to see this in Prague. I saw the Mucha gallery in Prague many years ago on one of my spontaneous trips to Europe, and it was spectacular.) Number three adds the yellow, number four the blue and so on. In the image ‘Hamlet’ you have only a few colours. This is the skill of the art for the printers as well as Mucha. The printer is inking up the images. There was an important working relationship and collaboration between Mucha and the printers.

Throughout the tall images, there is a split in the middle. In ‘Hamlet’, you can see some mistakes where the gold has slipped a little, and the purple has slid slightly. However, the mistakes add to the artistry and beauty as a whole, and this takes away the preciousness of the overall piece.

‘La Samaritaine’ is a biblical piece, stylised and in a Middle Eastern style. A Hebrew word ‘Jehovah’ is placed within the work. Mucha constantly takes account of these important references. Mucha said that Sarah Bernhardt had an expressive and beautiful face. In some images she is ageing. We see the beginnings of the technique of ‘airbrushing’ as a modern invention, where he adjusts the drawing slightly, at the same time, retaining the sensuality of Sarah in this piece.

Mucha read many scientific works on art and composition for example, what shapes and lines worked well together and caught the viewer’s eye and interest. In ‘Gismonda’, he decides on circles and curves He takes this idea of circles and whiplash curves to the extreme in many of his works.

His work for advertising was plenty. His poster ‘Trappistine’ uses the visual navigation to guide you to the product. You have the elongated figure and long hair all guiding the viewer towards the bottle which stands out. He is looking at the product and using imagery such as crosses from the label on the bottle and placing these into the background of the overall artwork. This provides an interlinking of symbols, meaning and composition. The idea that the drink is made by monks cross-references to the idea that there are hidden symbols and meaning within the work. This is about the beauty of the poster. He is selling beauty. The bottle becomes incidental.

In the poster ‘Monaco Monte Carlo’, the tour guide showed us the poster advertising The Monte Carlo railway line. We are made aware of the fact that this is about beauty. We are almost not seeing the advert it is so beautiful. If you are in a station in Paris, you have probably never seen a poster advertising the railway like this. It draws you in. It is more than an advert. It is about movement. There are floral garlands representing the wheels of the train. The stems are the tracks and spokes. There is a beautiful woman. The poster is a wonderful example of making something look wonderful to advertise the product. Yes, they are advertising posters, but Mucha is a deep thinking artist. He believed that art should be accessible to everyone, all classes and backgrounds

”The public would stop and see the posters on their way to work…The Streets became open-air art exhibitions”.

People tried to take the posters off the walls. They were enormously popular. In some ways, the accessibility of his work could be seen as equivalent to the work of Banksy in the way it became Street art and available to the masses.

Decorative commercial art could also be bought for walls. The text could be removed. These could now be sold as artworks in their right. There is no deep meaning to these works. This is about beauty, the image, the feeling and sensation this has upon the viewer. The works ‘The Seasons’ you could buy as large panels. They were licensed and used all over Paris. Paris is pushing Mucha’s artwork all over the city. Mucha was democratic and wanted his artwork in the poorest communities and houses also. He wanted his art to be part of everyone’s life, not just those who had money and could afford his art.

Art Nouveau and Mucha are inextricably linked. He is the godfather of Art Nouveau.

It took its inspiration from the arts and crafts movement, taking its inspiration from nature, the organic, the decorative to make things beautiful. Mucha’s interpretations were all decorative. Art nouveau means new art. However, he wanted to be known as an artist, not an art nouveau artist. He did not want to be pigeonholed just because he created decorative imagery.

He believed art changes and progressed. ‘The Flower Series’, Rose Iris, Carnations and Lilly are beautifully designed. There is a classical fluid female form. Not similar to Klimt which looks more modern, gold and flat. Mucha instead was looking back to classical times.

Mucha worked from life. He is then stylizing the figures. The depth of tone within these lithographs is maybe eight colours and shading, nixing of colours, a cloudy mottled effect, fine and detailed works. They look hand coloured but are not.

The skill and artistry of the team, the partnership between artist and printer is incredible. The end of 1894 to the end of 1898 covers the period of his progress of this outstanding art called The Style. The 1800s was an incredibly productive period. We have lived with Mucha’s art for many decades, through the sixties and seventies, his style weaves in and out of time and our lives, and we instantly recognise these works.

It is interesting to note how art nouveau travelled through Europe and Paris to the UK. The Glasgow School of Art were particularly involved with this style. ”James Herbert MacNair (23 December 1868 – 22 April 1955), was a Scottish, designer and teacher whose work contributed to the development of the “Glasgow Style” during the 1890s.

Born in Glasgow to a military family, MacNair trained as an architect with the Glasgow firm of ‘Honeymoon and Keppi’ from 1888 to 1895, and it was there that he first met Charles Rennie Mackintosh. ‘As part of their training, the two attended evening classes at the Glasgow School of Art between 1888 and 1894, and it was there that they met the MacDonald sisters Margaret and Frances. MacNair would go on to marry Frances, and Mackintosh would marry Margaret.’

All four later became the loose collective of the Glasgow school known as “The Four.”

MacNair was interested in Art Nouveau and the arts and crafts movement and became a significant influence as a teacher following his move to Liverpool in 1898 and was appointment as Instructor in Design at the School of Architecture and Applied Art.”

Do read up on the Glasgow Four. They are an interesting group of artists. I was particularly interested in Frances, wife of MacNair who mysteriously seems to have not been as recognised as much as she should be for her achievements. In the mid-1890s the sisters left the School to set up an independent studio together. They collaborated on graphics, textile designs, book illustrations and metalwork, developing a distinctive style influenced by mysticism, symbolism and Celtic imagery. Frances also produced a wide variety of other artistic work, including embroidery, gesso panels and water-colour paintings. Like her sister, she was influenced by the work of William Blake and Aubrey Beardsley reflected in her use of elongated figures and linear elements. Around this time Frances and her sister Margaret became members of ‘The Glasgow Girls’ which comprised women, artists and designers. The sisters exhibited in London, Liverpool and Venice. Much creativity was taking place when Mucha’s works became famous.

Mucha was familiar with Edward Burne-Jones whose works he went to see exhibited in Paris. One artist linked with Mucha was August Rodin whose works are also exhibited in this exhibition.

Rodin was the most important sculptor of the century. He was not influential to Mucha regarding style. But Rodin would have inspired Mucha who created a sculpture. Do look at the sculpture by Mucha and the amazing sculptures by Rodin. This sculpture highlights, Mucha’s skills. Look at the figure and the form of the work. This is a key work. He is not just a commercial artist. He is a fully rounded artist who does commercial work. Look at the photograph of Gauguin playing piano in Mucha’s studio. Gauguin is not wearing trousers in this photograph. Who would link Gauguin and Mucha together? They partied together. They shared a studio together. We associate Gauguin with post impressionism. Mucha also taught alongside Whistler. Yes, Mucha did decorative work, but he is also respecting brand new ideas in art. He is living in Paris when art is changing. Getting to know Rodin allows him to explore what art means.

In the late 1890s. Mucha also received a commission for the Paris exhibition to do with Bosnia and the Balkans, a chance to explore his own culture. Now he has a real chance to tell a story in his southern Slavic murals. He wrote to Rodin saying he felt the joys and sorrows of his Slavic people. He focuses on his cultural identity. In his painting ‘Song of Bohemia 1819.’ a beautiful painting, drapery, fluidity, flora Garland’s, pastel tones. Looking at it closely this is an impressionistic technique. 1918 is the creation of the public of Czechoslovakia. Mucha accepted no money for these commissions He was celebrating his country and heritage. His work ‘Russia must recover’ 1922 is referencing millions of people who died during the first world war. He was commissioned to create a poster to show what was happening.

This poster is not about beauty. ‘Russia must recover’, 1922 study for the poster. ”The poster served as a plea for help for starving children during the Russian revolution and civil war 1917- 22 which paralysed the country and killed millions through widespread disease and starvation.” This poster changes opinions, raises awareness, a mother holding her dying child, a powerful image that shows what is going on. It has a personal aspect to it. It refers to 1866, the war between Russians and Prussians, there were many deaths and an outbreak of cholera. Mucha lived through these times. It is a negative powerful image.

In 1911 to 1926 Mucha worked on a series of paintings to depict the important moments in Slavic history.

‘The Slavic Epic’ cycle No.10′, shows the most important gathering which took place South of Prague on 30th September 1419. A crowd gathers to hear a radical preacher call on them to take up arms to defend their faith.

The key thing about his sketch depicts the bottom corner of his painting. He started them at 51 and finished at the age of 64.

During the second world war in the Spring of 1939, Mucha was among the first person’s to be arrested by the Gestapo. During his interrogation, the ageing artist became ill with pneumonia. Though released he may have been weakened by this event and died in Prague on 14th July 1939.

In 1963 Mucha was re-evaluated as an artist. The Mucha Foundation was founded in 1992 following the death of the artist’s son, Jiri by his wife Geraldine and their only son, John Mucha. Most of his artist’s life was spent working on Slavic identity. Mucha created The Style.

Words: Alice Lenkiewicz © Artlyst 2017 Photos courtesy The Walker Art Gallery Liverpool

Only One Week To Go – Not to be missed, this exhibition presents Mucha in a way he has never been seen before

Alphonse Mucha In Quest of Beauty 16 June – 29 October 2017 The Walker Art Gallery Liverpool