Harland Miller’s rather handsome exhibition at White Cube, Mason’s Yard, looks more like the end of something than the beginning of something. There are several reasons why this is so.

Before embarking on these, however, it is worth taking a quick look at Miller’s career. Born in 1964, he straddles the great divide – the important frontier that divides those who grew up with the Web as already a commonplace in artists’ lives and those who had a life before that. Communication through the web didn’t really hit its stride until the middle of the 1990s. Before that print was still dominant.

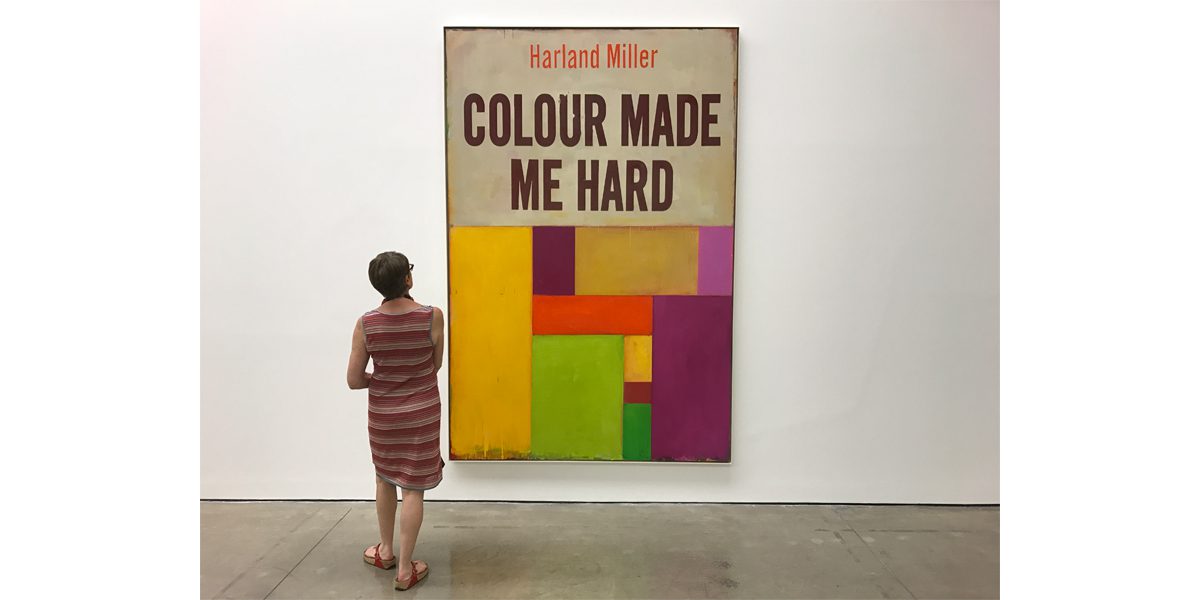

With their bold saturated colours, these paintings reference American abstraction

Books, specifically book covers, are a basic reference for practically everything Miller produces. Not the sort of book covers referenced by Richard Prince – no images here derived from cheap romance novels about members of the nursing profession. As the press release for the show tells one, the reference is to the artist’s ‘extensive archive of psychology and social science books that date from the 1960s and 1970s’:

‘Characterised by their bold and colourful abstract covers, these books embraced a positive attitude and the possibility of “fixing” disorders through a process of self-help. The geometric cover designs not only drew parallels with contemporary abstract painting but also provided a foil to the darker aspects of neurosis addressed by the book’s content.’

By focusing on this particular, rather specialised area of subject matter, Miller manages both to have his cake and eat it. The paintings are fashionably appropriationist, yet not crassly so. They manage at the same time to be, at first glance anyway, boldly abstract designs. Bold lettering, combined with geometric forms. As the press release also declares:

‘With their bold saturated colours, these paintings reference American abstraction, and in particular Robert Rauschenberg and Ed Ruscha’s use of vernacular signage and motifs.’

What this description tends to leave out is the fact that the paintings make a powerfully nostalgic impression. The colours may indeed be bold, but they are also subtly blurred and tarnished. The books they celebrate on a very large scale are somehow visibly second-hand.

Not representations of the sparkling brand-new paperbacks ranged on the scrubbed shelves of some trendy 1970s bookshop, ready to enlighten a new generation impatient with the fusty values of their elders, but gigantic versions of the sad, now slightly dog-eared self-help volumes you might today find piled up in some corner of a branch of Oxfam. Huge remnants from some drastic house-clearance, left-overs from some intellectual maiden aunt’s pitiful estate.

It’s clear from the artist’s own comments, and also from his writings – he is a successful novelist and intellectual commentator as well as being a widely exhibited painter – that he is not unaware of this persistent echo. One of his books is a study of obsessive-compulsive disorder, based on a set of found polaroids. It is called First I Was Afraid I Was Petrified. The title comes from the song by Gloria Gaynor, ‘I Will Survive’ – defiant, but not declarative of universal optimism. Another book is called International Lonely Guy.

One feels for him, but these paintings certainly don’t seem to point towards any kind of future development in art. They seem, instead, like big posters saying; ‘Yes, folks, you’re right. I’m here to tell you that contemporary art, the product of my generation at least, has hit the buffers. Don’t kid yourselves, we’ve reached a dead end.’

Top Photo: Harland Miller P C Robinson © Artlyst 2017

The Exhibition Runs Until 9 September White Cube Mason’s Yard London Visit Exhibition Here