The Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors show now on view at Gagosian Grosvenor Hill neatly pips Tate Modern to the post. In March 2018 Tate Modern unveils Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame Tragedy, its first ever solo show devoted to this most celebrated of all Modern Movement artists.

Picasso, steeped in the classical culture of antiquity – this, despite his role of as one of the primary creators of the new Modernist sensibility

While it’s nice to be offered such a feast of Picasso’s work, all at the same time, one detects a competitive edge to this apparent coincidence. The Tate show, standard ticket price, will cost you £19.50 to get in. The Gagosian show, curated by none other than Sir John Richardson, still – aged 90 – labouring through his monumental, unfinished, multi-volume biography of the artist, comes for free.

Tate increasingly makes a big deal about its commitment to populism, but the major London commercial galleries now compete and undercut. If you’re a skint student, or, for that matter, a skint old-age pensioner, which do you choose to go to? Capitalism triumphs OK, bureaucratic self-righteousness be damned.

The Gagosian show covers a much wider time-span than the Tate effort, which focuses on a single year. But it’s noticeable that quite a lot of the material on view comes from the same crucial moment in Picasso’s career, the beginning of his last truly great creative phase.

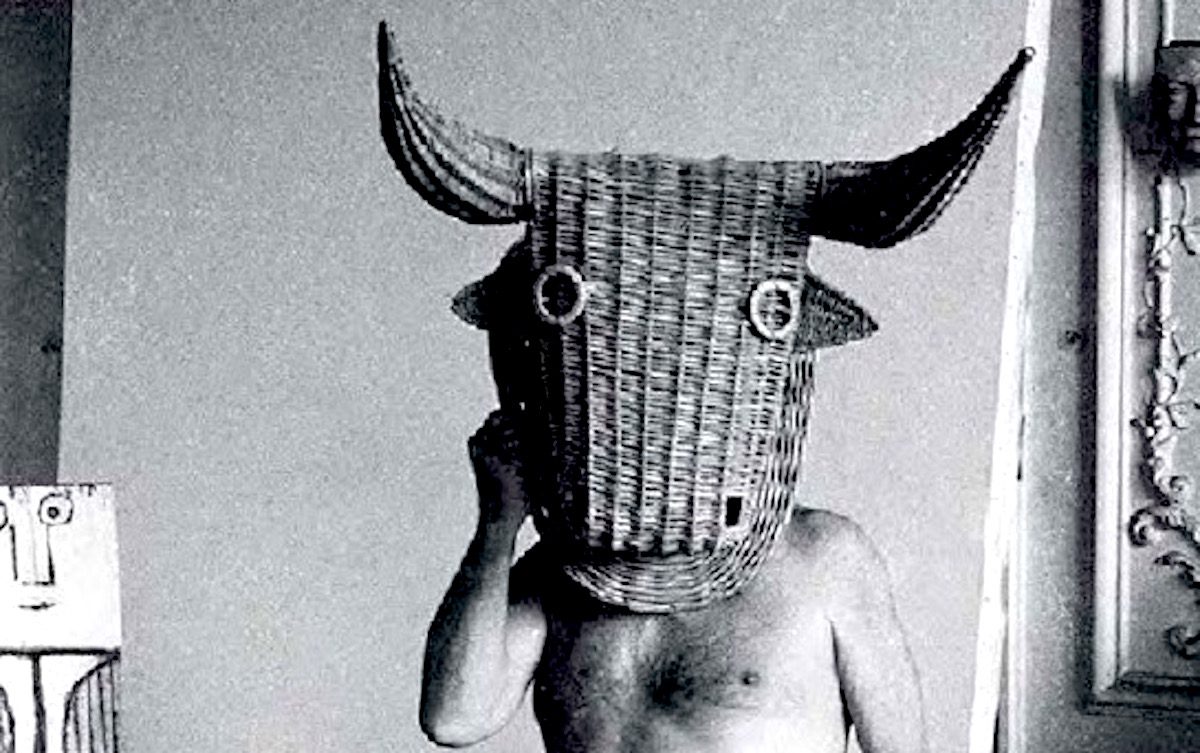

Bull fights and bull fighting were one of Picasso’s enduring links to the traditional Spanish culture he came from. Long expatriated from Spain, he retained his passion for this sport-cum-ceremony all his life. The Gagosian show contains documentation about this is the form of photographs and posters, quite apart from the works of art on view.

Picasso, steeped in the classical culture of antiquity – this, despite his role of as one of the primary creators of the new Modernist sensibility – was also fascinated by the legend of the Minotaur, the monster whom the hero Theseus tracked down and slew in the Cretan labyrinth. He saw the Minotaur as an avatar of himself – dangerous, demanding human sacrifice, ready to kill whoever challenged him or got in his way, yet at the same time a predestined victim. He also seems to have seen himself as both protagonists in the Spanish bullfight: both the bull that gets killed, and as the torero who, in turn, has a good chance of getting slaughtered.

The role of sacrificial maiden was played by, or imposed upon, his mistress Marie-Therese Walter, aged just seventeen when she first became involved with him in 1927. Picasso, born in 1881, was then on the verge of middle age, and no doubt just beginning to feel threatened by advancing years, though he was to live a long life.

Their connection lasted until 1940, and Marie-Therese had a daughter by the artist, who never married her, though their affair caused his wife Olga to leave him. Marie-Therese committed suicide in 1977, three years after Picasso’s death. One may say that the Minotaur killed her at last. In fact, almost none of the women Picasso got involved with survived him successfully. Picasso’s grandchildren from his daughter by Marie-Therese, are, however, still very much involved with the Picasso industry.

The Gagosian show, adroitly curated by Richardson, amply illustrates these complex themes, mostly through sequences of drawings, were how one can see how a motif evolves as Picasso tackles it again and again. Among the fascinating things on view is not an original artwork, but some projected clips from Paul Haesaert’s film Visite a Picasso (released in 1949), where the artist stands, against a dark background, behind a huge sheet of glass, and draws on the surface of the white paint. The figures he creates evolve before one’s eyes. Long before the fashion for ‘performance art’, now so enthusiastically patronised by Tate, Picasso was a master of the genre. The difference is that there isn’t a trace of am-dram about what he does. The image evolves. One is, thanks to the camera, privileged to watch.

PICASSO: MINOTAURS AND MATADORS CURATED BY SIR JOHN RICHARDSON April 28–August 25, 2017, 20 Grosvenor Hill London WC1K 3QD

Lead image: Picasso wearing a bull’s head intended for bullfighter’s training, La Californie, Cannes, 1959

PhotoDetail by Edward Quinn © edwardquinn.com