The hosannas have already begun. Picasso’s latest show at Tate Modern, entitled Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy gets a 5-star review in The Times. Nestling up close, on the same page, there is a carefully exculpatory text headed ‘Picasso wasn’t a monster, says granddaughter’. Tell that to the ghost of an artist who sometimes portrayed himself as a reincarnation of the Minotaur – the Cretan bull-man, housed in a maze, to whom maidens were sacrificed.

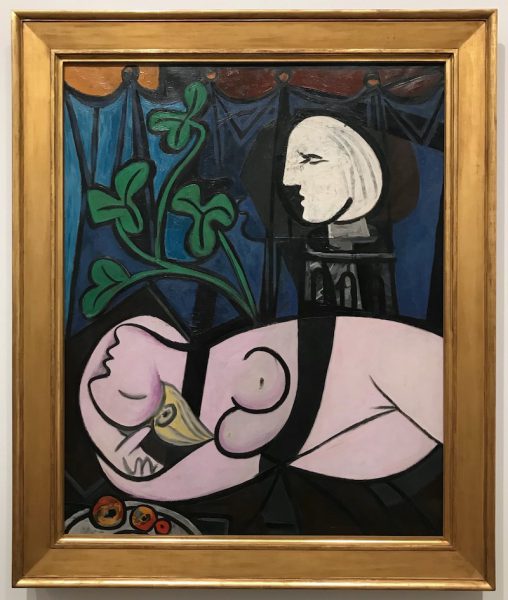

Marie-Thérèse is also that of an oriental odalisque: the passive focus of male desire – ELS

The granddaughter in question is Diana Widmaier Picasso, the child of Maya, who, in turn, was Picasso’s illegitimate daughter by his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. The Tate show has, as its major theme, the doomed relationship between these two protagonists. Picasso was then a highly successful artist, just entering middle-age, married to a former, rather repressively respectable dancer in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, inhabiting an apartment in the fashionable rue la Boétie in Paris, with a country place, in addition, a rather-rough-and-ready chateau at a place called Boisgeloup, about sixty kilometres outside of Paris, sufficiently rich to be transported between the two in a large Hispano-Suiza limousine.

Marie-Thérèse, whom he encountered by chance in a Paris street, was, when they first met, a naïve 17-year old, blonde, athletic girl with the kind of profile that made her look like a classical sculpture. The encounter took place in January 1927, outside the Galeries Lafayette department store.

For most of the years of their sexual relationship, Picasso kept her very much concealed from the fashionable circle he frequented socially in the company of his wife. When he eventually replaced her, it was with another, more intellectual mistress, Dora Maar, who saw him through the difficult war years. Their relationship, however, lingered on beyond this, into the period when the artist was linked to Françoise Gilot. Picasso continued to provide financial support. When Olga Picasso finally died Picasso rang Marie-Thérèse and asked her to marry him. She refused, and they never saw one another again. She committed suicide in 1977, four years after Picasso’s death.

All in all, hardly the kind of story to win the approval of the #MeToo brigade, with whom Tate, in other upcoming projects, seems increasingly inclined to ally itself. The problem is, of course, that the early history of the Modern Movement is full of personal histories of this sort. Modigliani, another Modernist ‘bad boy’, is currently the subject of another major show at Tate Modern, which runs until 2nd April.

There are, I think, three things that give Tate Modern’s new exhibition its impact. First, there is its alliance to the past. Revolutionary as many of these paintings and sculptures are in their intentions; they have close links to the art of the past. In particular, the violently – one might almost say savagely – erotic presentations of Marie-Thérèse are closely linked to the European Neoclassicism of the early 19th century. One is everywhere aware of the presence of Ingres. Where Picasso, in an earlier phase, had expressed his fascination with African tribal art, scorning his fellow Cubist Georges Braque ‘because he was not superstitious’, here one is constantly aware, not only of Ingres but also of the Greeks and the Romans, whose works have so often come down to us a violently shattered form. In fact, the damage is part of their fascination.

Second, there is here, as there is also in the work of Matisse – the contemporary whom Picasso most admired and perhaps most feared and envied – an orientalising element. The image of Marie-Thérèse is also that of an oriental odalisque: the passive focus of male desire

This is particularly striking because the chosen model is also the essence of the kind of Aryan blonde who was to fascinate the Nazi movement in Germany – a movement that, during the time when these paintings were made, was just at the beginning of its rise to power. Picasso clearly feels the seduction of this archetype (it was, after all, for her looks, not just for any other qualities that she might possess that he made an effort to pick her up at their first encounter in the street). He also, typically, feels a savage urge to disrupt – dislocating body parts, offering sly metaphorical comparisons. In the cover-image used for the exhibition catalogue, a painting called The Dream, which shows Marie-Thérèse, sweetly smiling, seated asleep in a red armchair, the upper part of her tilted head metamorphoses itself into a penis.

This kind of disruption was something that Picasso learned from his association with the Surrealists, a movement then just beginning to dominate the Parisian art world. He never, however, fully associated himself with it. Instead, he looted: stole what he wanted

The third thing that needs to be taken into account, given both the times we now live in and the drift towards self-congratulatory goody-two-shoes political statements now typical of the supposedly avant-garde art world, is that this is not in any sense a political exhibition.

These violently erotic, yet classical works were made before Picasso, the emigré Spaniard, made his momentary alliance with the politics of his time by painting a single, never-repeated masterpiece: Guernica. He passed the war years surprisingly undisturbed, in Nazi-occupied Paris. It was only when Nazism was defeated that he returned to politics, allying himself uneasily with Communism and painting Les Massacrés de Korée to condemn American intervention in Korea. I don’t think any admirer of Picasso’s art feels that this was a well-judged second sortie into the political realm.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2018