The R.A.’s new exhibition, hot on the heels of its magnificent Ab-Ex show, is entitled Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932. That is, it aims to cover what happened in Russian art during the first period of Soviet rule. The show arrives, I think, at a particularly timely moment, when artists here in the West have fallen in love all over again with the idea of supposedly avant-garde art as a vehicle for promoting supposedly leftist political causes. As such, the event at the R.A. offers a spectrum of what can only be described as awful warnings.

This doesn’t mean, however, that it isn’t replete with fascinating artworks, nor that it doesn’t echo with fascinating and original curatorial ideas. Anyone who thinks they are a friend of contemporary art ought to go see it.

“Anyone who thinks they are a friend of contemporary art ought to go see it” – ELS

Though Britain is a democracy run on capitalist principles largely inherited from the 19th century, many of the problems we now have with presenting and promoting new art in harmony with the accepted social ideas of our time first surfaced in acute form during the early decades of the Soviet regime.

The Russian Futurists, whom we now think of as representing the true creative spirit of early Communist Russia, were, from the very moment when tsardom fell, in conflict with and suspected by the new Soviet masters of their country.

These masters, though radical in politics (at least in their desire to get rid of the governmental structures that had existed previously and to build new ones that matched their own ideas), were nevertheless instinctively conservative in their visual tastes – something that was also true at that period of the mass audience they wished to instruct and influence.

If one looks at key Futurist artists, such as Malevich – splendidly displayed in the show – one notes that his lasting influence was not upon art as the rulers allowed it to develop in his and their own country, but on what happened in due course to visual imagery in the capitalist West. There was, in particular, an enduring influence from Futurism on the kinds of visual shorthand that have become an integral part of the language of today’s advertising industry. To the point, maybe, where one can see Russian Futurism as the granddad of some aspects of Andy Warhol’s Pop Art. In Warhol’s multiple images of Elvis on the same canvas, for example.

Where Russian art of this early Soviet period progressed towards the future with least official resistance was through photography, an aspect that is amply illustrated in the R.A. exhibition through examples of the work of Alexander Rodchenko and Boris Ignatovich. This, perhaps, was because photography was instinctively regarded by the new political masters as a safely, but due to its technological nature neutrally, populist form.

The exhibition also very convincingly documents the fact that there were other kinds of art, not necessarily anti-progressive, which flourished in the early Soviet period, that nothing to do with the Futurism inherited from immediately pre-Revolutionary Russia. A whole section, fully equal to the section devoted to Malevich, is given to the work of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, who is much less known here in the West. Petrov-Vodkin was a realist but nevertheless distinctly non-conformist master – non-conformist in subject-matter, but also in subtle nuances of spatial experimentation. His work may perhaps be regarded as the great discovery of the show.

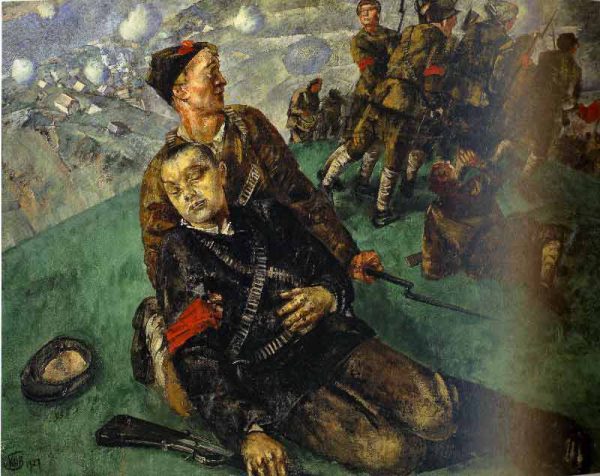

One of the most striking works in the show is Petrov-Vodkin’s Death of a Commissar , which has a much greater emotional impact than anything by Malevich – though perhaps ‘emotional impact’ of this directly human sort wasn’t, in fact, something that Malevich was striving for.

Much of Petrov-Vodkin’s work, especially compositions containing human figures, refers the spectator back to the religious art of the past. For this reason, perhaps. Death of a Commissar was kept hidden away in Soviet times.

In fact, this religious echo can be found in a great deal of Soviet art, even after the clampdown that happened after 1932, when the show’s narrative comes to a close. Heroes of Soviet Labour, painted by Socialist Realist artists fully approved by Stalin’s regime, were surrogates for the Orthodox saints depicted in icons. And Petrov-Vodkin’s martyred commissar, with an added halo, could certainly find a place as the chief personage in the altarpiece of a church.