It’s become noticeable that while the British art world – it’s museum dominated segment in particular – still prattles happily about ‘emerging artists’, convincing examples of this species have become rarer and rarer. When they appear, they are usually much older than the enthusiastic adjective implies. ‘Emerging from what?’ one is tempted to ask. ‘Out of a pond, (Submerging Artists?) or from under a stone? ‘

A lot of commercial, as opposed to official, attention is being directed right now at artists who are best described as ‘golden oldies’

Some rare artists placed in this category do of course deserve the description ‘emerging’. Chief among them recently has been the 83-year-old Rose Wylie, whose delicious (and deliciously titled) show Quack Quack recently closed after a very successful run at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery. Wylie was essentially unknown until she won the John Moores Painting prize in 2014. In February 2015 she was elected RA. In the same year, she won the Charles Wollaston Award for ‘most distinguished work’ in the RA’s Summer Exhibition. Well-deserved honours, all of them.

In marked contrast to this, a lot of commercial, as opposed to official, attention is being directed right now at artists who are best described as ‘golden oldies’. Fully emerged as she now is, Wylie would fit comfortably into this category too.

If one looks at what is happening in some of London’s grander commercial galleries, many of which have moved out of Mayfair into more conservative St James’s, south of Piccadilly rather than north of it, this prediction is becoming increasingly marked.

One example particularly comes to mind. It is the sequence of shows currently being devoted to the work of 80-year-old William Tillyer, at the Bernard Jacobson Gallery in Duke Street. Now that celebrations for David Hockney’s 80th have more or less concluded, there is room for other artists in the same age-group to – yes – ‘emerge’. Or at any rate to stick their venerable heads above the parapet.

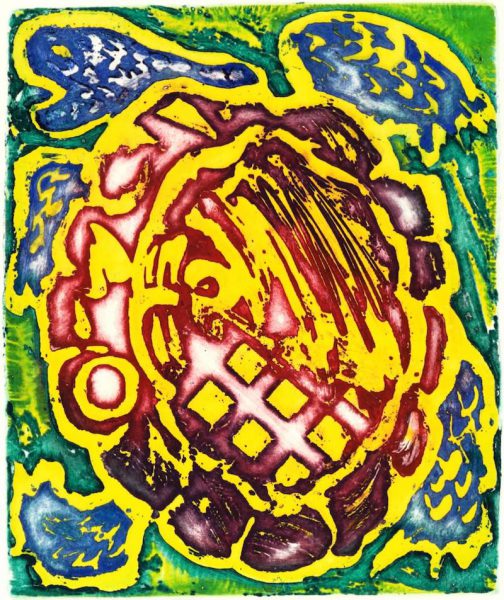

Tillyer will be the subject this year of a five-part celebration of his work. The first part, entitled simply A Radical Vision, is already over. Current is a show featuring illustrations to Joris-Karl Huysmans’ A Rebours (Against Nature, 1884), accompanied by a handsome book with a translation of Huysmans’ text by Theo Cuffe

Still to come are three more segments. One will be a series of watercolours illustrating a suite of poems entitled Nobody, by Alice Oswald, who is undoubtedly flavour-of-the-last-several-years in British poetry – named last year as BBC 4 Poet in Residence This segment opens on 15th May. And in September, there will be a major book about Tillyer put together by his faithful dealer, Jacobson.

I think one of the lessons in all this is the continuing stubborn survival of the old Modernist ethos, in the face of the facile moralising and the equally facile cult of ‘appropriation’ now so characteristic of official British art. Against Nature has, in fact, often been presented as an anti-moralistic text. Modernist admiration for it was linked to a rejection of Victorian hypocrisies.

It is in fact very difficult to impose any kind of obvious stylistic coherence on Tillyer’s work. Some works are splashes of colour, in what one might call the J.M.W Turner tradition. Some are grids. Some of the illustrations to A Rebours are downright creepy. I’m thinking here of a group of three prints, The Hanging Tree, 1, 2 & 3, which show hacked up bits of human bodies, tied to poles. These are prompted by the admiration felt by Des Esseintes, the hero of A Rebours, for a series of engravings entitled Religious Persecutions made by the 17th-century Dutch engraver Jan Luyken. Des Esseintes presumably valued these strictly for the horrors they depict, not for any moralistic or religious message the artist may have intended.

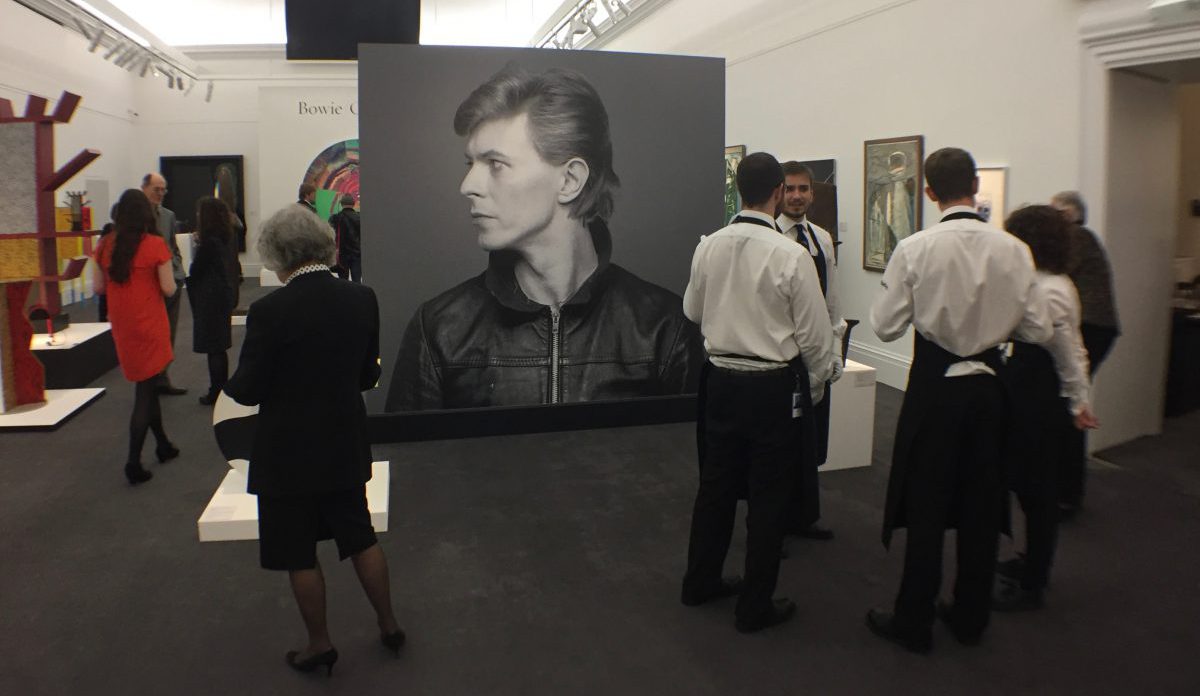

Another exhibition currently on view in London, a step or two away from the Jacobson Gallery, reinforces the idea that Tillyer is, in fact, a surviving scion of the English 19th century Romantic Movement. This is a show of late work by Peter Lanyon (1918-1964) at Hazlitt Holland Hibbert (until 16 March). Lanyon was a member of the flourishing mid-20th century St Ives school of artists, lost in his prime through a gliding accident. He is now remembered chiefly as part of the resilient British landscape tradition, and perhaps more specifically just now because David Bowie admired and collected him. Work that belonged to Bowie is present in the show.

Looked at again, half a century after the artist’s death, they seem oddly prophetic. What looks like mechanical forms intrude into the landscape, just as they do in some of Tillyer’s compositions. And, yes, they too have a faint but perceptible current of unease. One has no idea if Lanyon read A Rebours, but one feels that, for all his commitment to the romantic cult of nature, he quite possibly might have done.

William Tillyer | À Rebours Bernard Jacobson Gallery 15th February – 10th March

Peter Lanyon: Cornwall Inside Out Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert 9 FEBRUARY – 16 MARCH 2018

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Top Photo © Artlyst 2018

Read: Edward Lucie-Smith Bids A Final Farewell To The Avant-Garde

Edward Lucie-Smith was educated at King’s School, Canterbury and Merton College, Oxford, where he read History. He is an internationally known art critic and historian, who has published more than a hundred books including more than sixty books on the subject of art, chiefly but not exclusively on contemporary work. He is generally regarded as the most prolific and widely published writers in this field.