In October 1999, when the exhibition Sensation opened at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Mayor Rudy Giuliani – he of the running hair dye and lawyer to Trump – threatened to close it down on the grounds that the image of Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary was religiously offensive.

The jewel-like surface of the painting is made up of a shimmering gold ground – SH

Whilst the negative reaction to the exhibition in this country was largely based around Marcus Harvey’s gratuitous image of the Moors Murderer, Myra Hindley, created from a series of child handprints, for America, a pious country that believes it has a God on its side, an African Virgin Mary perched on two large balls of dried elephant dung was simply too much for the righteous people of the US of A to put up with. In protest, an elderly visitor declared it ‘blasphemous’ and smeared it in white paint.

Now, if that elderly visitor had read his Durkheim, he’d have realised that the sacred and the profane are two sides of the same coin. The sacred-profane dichotomy was a concept suggested by the French sociologist Émile Durkheim whereby: “religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden.” According to Durkheim, the sacred represents the interests of the community embodied in holy objects and totems, whilst the profane involved everything else that concerned daily life. Durkheim explicitly stated that the sacred–profane binary was not equivalent to a system of good and evil. The sacred might be either, as could be the profane. After all, the sacred could not really be sacred unless there was a concept of the profane to counter it. In fact, what counts as sacred and what counts as profane is often deeply ambiguous. For example, blood is profane to many Jews and Muslims but drunk as the blood of Christ in the Christian sacrament. Sex is taboo to many religions, which is why Mary was a virgin, but Herodotus suggested that the practice of sacred prostitution was practised in the temples of Babylonia and the Near East.

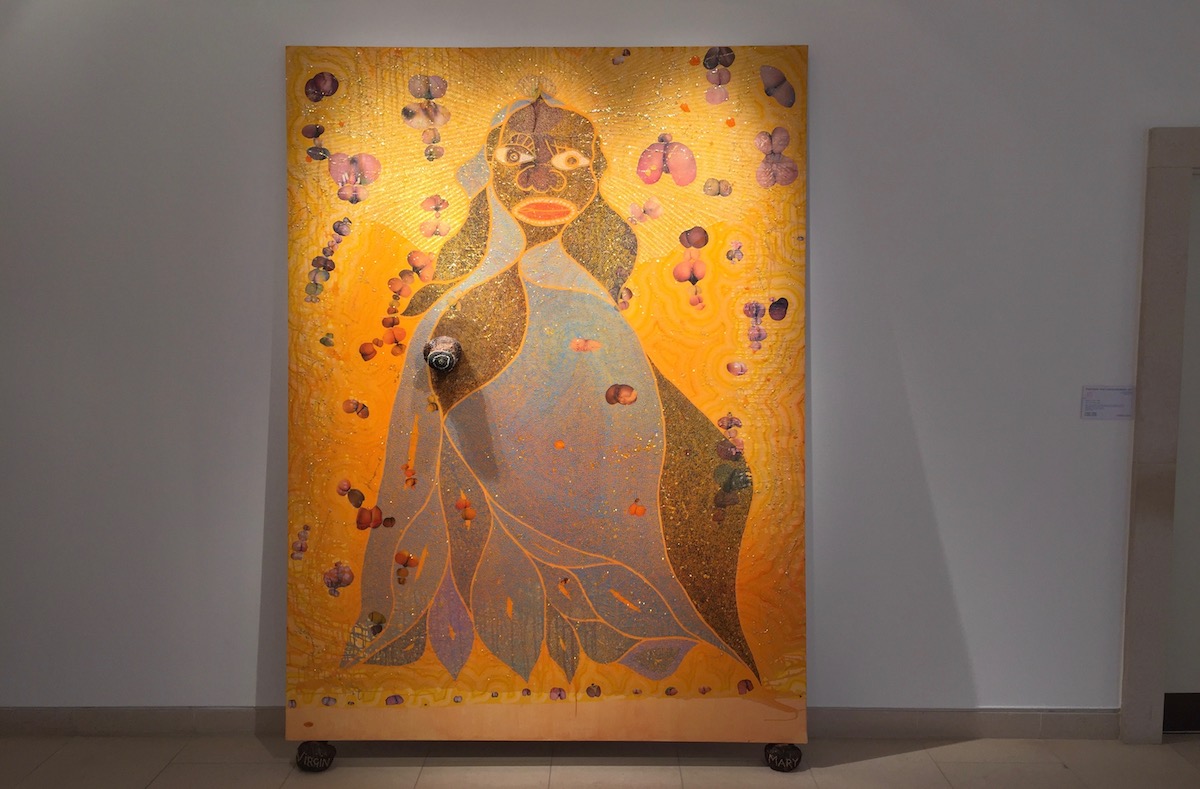

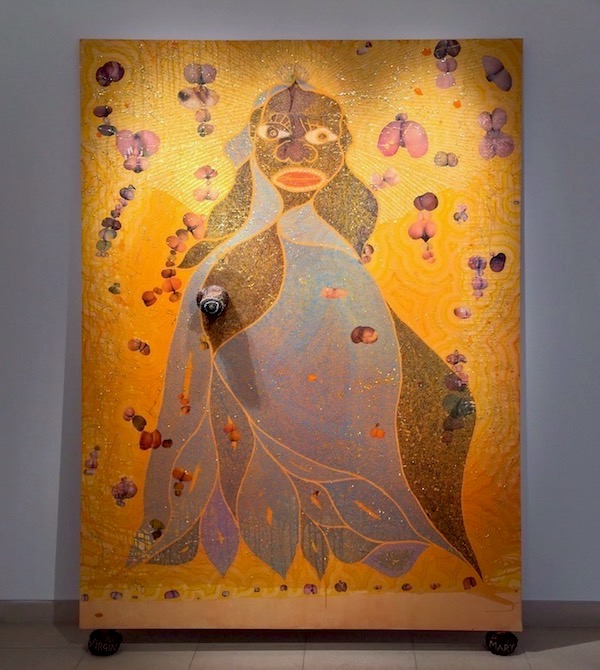

Standing on two balls of elephant dung inscribed with glittering letters that spell out the title of the work, Chris Ofili’s Virgin stares out directly at the viewer with her large googly eyes. The thick lips of her big mouth are sensually parted. She has a broad nose. It’s as if all the white tropes and caricatures of a black women have been brought together here but, in this case, are being used ironically by a black artist to suggest to his (presumably) largely white audience that they cannot see a black woman without sexualising her. The ubiquitous blue gown associated with the Virgin Mary falls open over her curvaceous body to reveal a sphere of lacquered elephant dung where her breast should be, and she is surrounded by cut out images from pornographic magazines of women’s buttocks, playing, again, with racial stereotypes around sexuality, availability and blackness. There is wit, here, too. For as Jesus’s was a Virgin birth, sex, let alone pornography, probably had little to do with it.

The image also asks us to consider why the Virgin shouldn’t have been black – a distinct possibility from the part of the world from which she hailed – and a critique of the assumed Anglo-Saxon Sunday School whiteness of many biblical figures. Ofili has said that: “As an altar boy, I was confused by the idea of a holy Virgin Mary giving birth to a young boy. Now when I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are. Mine is simply a ‘hip hop’ version”.

The jewel-like surface of the painting is made up of a shimmering gold ground created from dots of paint and glitter. This use of gold makes reference to the icons of the Byzantine world. Gold has been used in art as far back as the Incas, who believed it to be ‘the tears of the sun and in western Christian art, it symbolises the transcendent, divine light that embodies the invisible, spiritual world. It has also been used in the background to mosaics and altar triptych panels, in both Christian and Islamic illuminated manuscripts, as well as in the unique Passover text, the Golden Haggadah (c1320-1330), that probably belonged to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family in Spain. The psychedelic patterning, bright colours and batik inspired textured surfaces pay homage to African wax prints, known as Ankara and Dutch wax prints. These are a type of nonverbal communication between African women carrying their messages out into the world, with many named after cities or celebrities, places or specific occasions.

Born in Manchester to Nigerian parents, Ofili was awarded a British Council grant in 1992, which had a big impact on his work. This he used not to return to his homeland but to visit Zimbabwe, where he was inspired by the abstract rock paintings of the San Bushmen, the oldest inhabitants of Southern Africa, hunter-gatherers who’ve lived in the region for at least 20,000. As a result, his work became as concerned with decoration and visual sensuality as with politics. If Rudy Giuliani had had a little more culture, he might have realised that by incorporating high and low art and art historical narratives along with religious imagery and pop culture that Ofili was making a deeply eloquent and relevant contemporary image of the Virgin Mary for our times.

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic. Her novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth and her fourth poetry collection is due from Salmon Press, Ireland in the autumn.