Christopher Clack says; I have been making images for as long as I can remember, and for as long as I can remember there has always been an element of religious imagery or content in the work I have produced. Why this should be, I do not really know. What I do know is that the connection between religion and art is for me a profound one, one that I think has implications for the way we think about religion as well as art.’

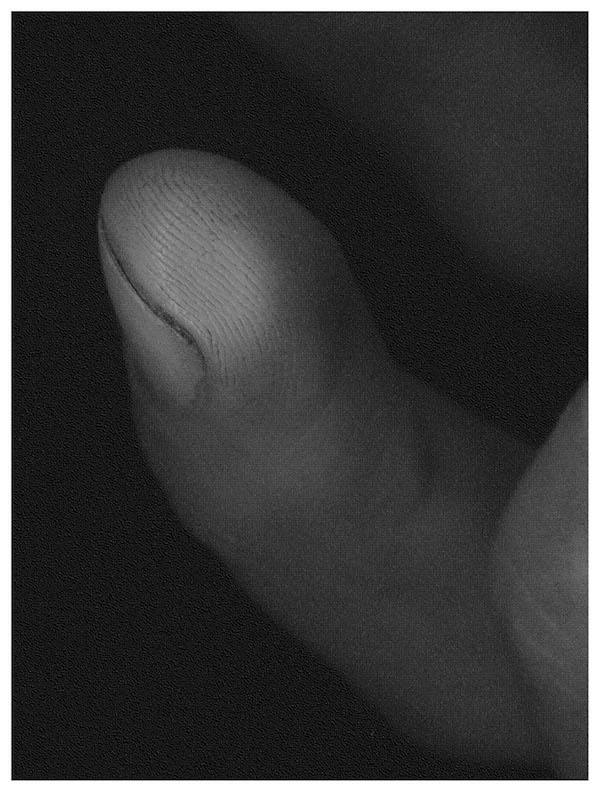

Clack studied at Camberwell School of Art and then at the Royal College of Art. His primary medium was oil paint, but he also loved etching and making sculptures. One essential aspect of all his work was the physical, tactile nature of whatever he made, so it seems strange to him now that he works almost entirely on computer. The surface had always been an important aspect in his work and, counter-intuitively, became even more critical in his move into digital. His images are now produced using scanners, cameras, and software such as Photoshop and paint programs like Coral painter, and then printed out using large format printers and the best quality materials he can lay his hands on. His challenge is to bring into this medium a sense of the physicality of things, generally felt to be lost in digital production.

There is a connection between the material and immaterial aspects of his work and his interest in the dynamic and inter-relationship between religion and atheism

He says that he started the website Modern Religious Art because he thought it would be about the most unpopular thing he could do. He also thought it would be interesting to see if any other artist wanted to be on it. As we discuss, for a variety of reasons, they did.

Clack’s work has recently been seen at the Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair, the RA’s Summer Exhibition and The Year of the Dog exhibitions.

JE: You’ve said that you’ve come to hang the ‘deep down need’, the ‘itch you just have to scratch’, the ‘something there that bugs you’, that pushed you into the art thing in the first place on ‘the nature of religion and religious thought in relation to art’. What is it about religious thought concerning art that has led you to do this? What is it about your own artistic need that has led you to do this?

CC: The ‘deep-down need ‘, ‘the itch’ is probably of childhood origin. My contact with formal religion was through school and my mother’s family, who were Irish Catholic. Both of these areas of contact filled me with a sort of dread and only increased a sense of separation from something. But I was interested in the imagery that came with religion. This seemed to me to come from something real.

I think later on, through the practice of making visual art, I think I came to see religion, formal religion, differently. Its initial effect on me, as a child, was to say, what you’re feeling is ‘out there’, making art has shown me that it’s something ‘in here’. JE: You have stated that ‘the way that contemporary art has developed has brought it closer to the origins and nature of the religious impulse.’ To what would you point as evidence for this thesis?

CC: Contemporary Art is very much to do with experience, and when we get down to our experiences, we find we have much in common with each other. Art when it comes down to it, and particularly in its practice, is generally not interested in doctrine or dogmas. When the different religions get down to experience and past doctrine, we find they share very much in common with each other, so, it seems to me, the commonality of religions and of art is the individual human experience. I think art shows us how to get to the heart of our experience. ‘What does it mean’ is not the appropriate question about contemporary art, but how does it alter my perceptions, does it open things up? Meaning is found, but in a relationship or engagement with the work, much as in any human relationship meaning is found in the engagement itself.

Art is, above all a practice. It is ‘doing’ and ‘living’. Religion, too, is a practice and something to be lived. Both have less to do with what we believe, and more to do with what we discover. This, I think, is common ground. What, if anything, do you see being built on this common ground? A place where religion looks more like art and art, more like religion.

JE: A press release for a show of which you were part suggested that you want ‘to find what ‘the Religious’ have lost, and maybe, at the moment, only art can do that.’ Discuss?

CC: I think religion needs to bring back in or emphasise its mystical aspects, which is a way of looking at the core of our experience, and I think this may be more comfortably approached by many people now via art.

JE: The Foreword to a recent Degree Show by MA Art and Science students suggested that art and science are ‘human efforts to comprehend and describe the world around us and our experience of it’. The one’ searches for truth in subjective experience and the other in objective reality’ and it is in the rift ‘between subjective experience and the objective reality where ‘art’ manifests.’ To what extent might this description of art also be true for religion and to what extent do you see overlaps between art and religion?

I don’t think I entirely agree with this description of the art. The idea that one’ searches for truth in subjective experience and the other in objective reality’ seems to me to be attempting to draw art into the world of science and some practical knowledge basis or purpose. It’s not that art or aspects of art practice cannot explore aspects of our physical and psychological world and develop from this a field of knowledge. Still, it seems a side issue in many ways to talk about an aesthetic experience in this way. Genuine aesthetic experience, I feel, comes with a sort of detachment that would preclude any considerations like search for truth or attempt to gain knowledge. I think this thought could apply to religion as well.

JE: What is negative theology and how does it relate to your art?

CC: In negative theology, the general idea is that we can never truly define God and that we need to transcend definitions to understand the nature of God. That we cannot speak about God, so we only spea of God in terms of what God is not, rather than thinking, we can describe what God is. I like this approach. It’s not ridged and is not confrontational and is very open to creativity and a poetic approach. One piece I made which is part of a set of small works has as part of the image the words, “in the imagination, our God resides” and “in god we are imagined”.

The antithesis of this is the world of fundamentalist thinking in religion, and, well, just generally any sort of fundamentalist type thinking. This may be a very glib comment, but any genuinely creative thought process seems to be inherently in conflict with any kind of fundamentalist approach to the world.

JE: How do you handle the aspect of negative theology that would seek to negate all images on the journey into God?

CC: I don’t think artists have any problem with negating images; creativity always negates. You cannot hold onto things, holding on is not a creative position, they are all let go and you move on. One thing art practice does is teach you how to let go. From what I have read of Eckhart, creativity is perpetual, on-going, so nothing is settled or resolved. This all seems to be very much imbedded in modern and contemporary art practice. Taken to its logical conclusion, negative theology is itself to be negated.

JE: The religious or spiritual motivation in your work has always been there. Has this helped or hindered the reception given to your work and has there been any observable change over the years concerning opportunities to show work which has a religious motivation?

CC: Well, from early on, I felt an uncomfortable reaction from people when I talked about religion being an aspect of my work, but the word religion can mean different things to different people, sometimes causing a slightly hostile reaction, un-comfortableness or just indifference.

JE: In 2008, you started the website www.modernreligiousart.com and invited other artists to show work on the site. What have you gained from this experience and how has it impacted your artistic practice?

CC: I think it was a worthwhile experience for me at the time. I think it reduced the sense of personal and artistic isolation, I met some interesting people and contacts, but I couldn’t keep it up. It attracted quite a lot of people on the wackier fringes of things, so I eventually gave up on it.

JE: To what extent did other artists take up your offer to show work on the site and what reasons did they give for responding?

CC: When I was focused on the site it was getting quite a lot of response, much of it from artists who were feeling that in terms of getting shows, gallery representation etc. the religious aspect of their practice was working against them. How true this was, I cannot be sure. I have had difficult responses from people, who, when they become aware of the religious content of my work, back off a little. But I feel that this has changed. Religious content in art does seem to be back and accepted more readily in a contemporary art context.

JE: You have exhibited in a wide variety of shows and contexts – from car parks to churches, the Summer Exhibition to the Venice Biennale. Which shows or contexts have been most exciting or challenging, and why?

CC: Well, straight away, I would say shows curated or instigated by Vanya Balogh. Vanya has a very particular curatorial style. Quite often lots of artists are involved, so you see a lot of other people’s art and get lots of feedback, and exhibitions are quite commonly held in challenging spaces like underground car parks. It has, at its best, pushed me into new work and methods. It’s also enabled me to meet more artists. I think I have always found being ‘out there’ somewhat challenging, psychologically or something.