Welcome to the first of a new series of monthly artist interviews by critic Paul Carey-Kent. There’s an aura of mystery to Ena Swansea. Her big, impressive paintings are now on show at Ben Brown Fine Arts (‘green light’ to 30 July), and I wanted to know more. Just how are they made, and why do they show what they do? So I arranged a Zoom with the artist in her New York studio…

How does your use of graphite in paintings operate?

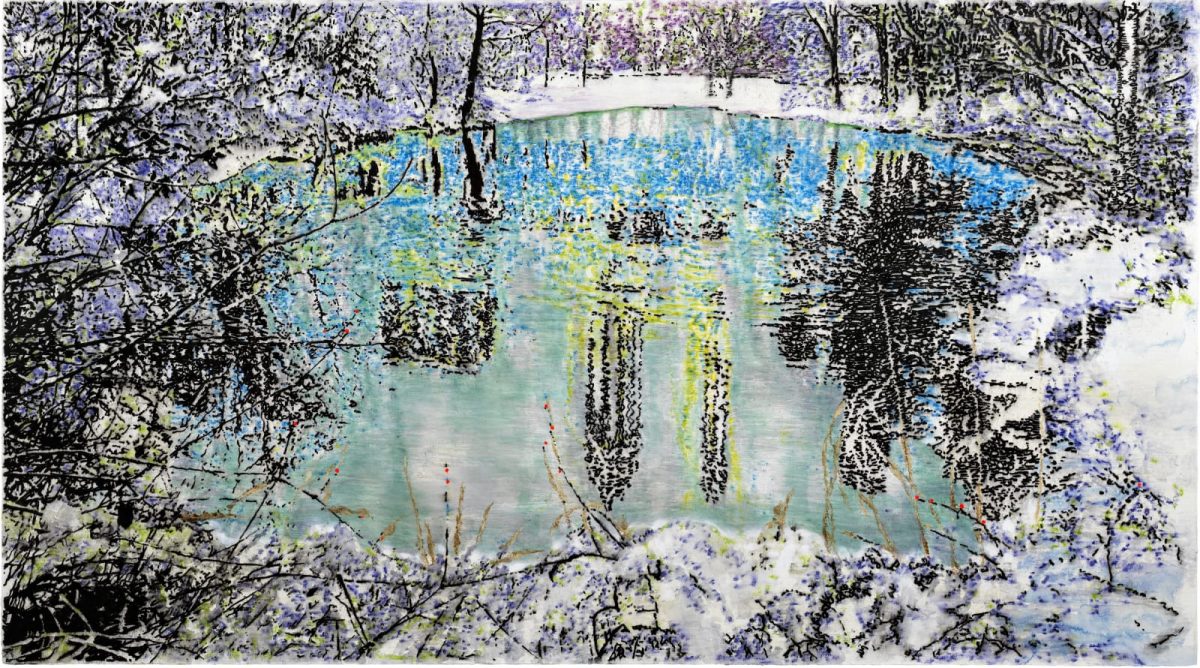

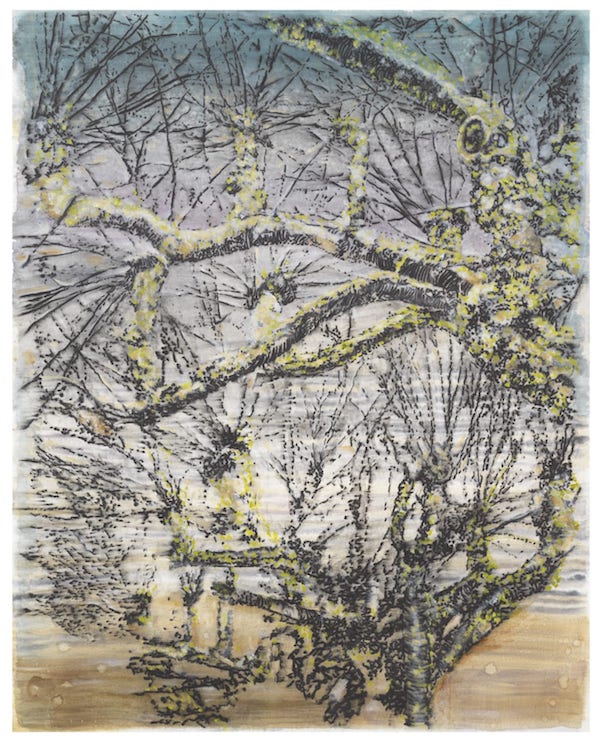

I discovered that graphite had this curious quality that it both sucks the light out of the image and also reflects and so brings light back into the image as you move around it. I’ve made many paintings on graphite grounds, but they only really thrive in perfect lighting – they can die otherwise. So I evolved into using what you might call graphite and its cousins… there’s oil, acrylic, mica, pulverised marble, ink, graphite and pastel in these paintings, including luminous and metallic pigments.

What effect does that intend?

I hope my paintings feel as if they could be turned on and off. As if you have just a nanosecond ago pulled the plug on an old TV. The images look unstable as if part is missing or out of focus. That echoes how, when I was a kid, US TVs only had 525 lines. Now, of course, we live by these glowing screens: it’s as if we have a doppelgänger who has another life, who lives in the screen and thinks everything is real in there…

You have a background in film, but I think it’s your photographs which provide your starting points?

Yes, looking back over the last few hundred paintings (see enaswansea.com), they feel like frames from a film that cannot be made. I’m revisiting things that I haven’t quite figured out. But I don’t shoot much-moving stuff – rather, I have a library of 165,000 photos organised by ideas, sometimes literary, sometimes particular subjects like ‘pollarded trees’. They look weird to an American; we don’t control our trees like Europeans. To me, they become anthropomorphic.

What places are we seeing?

Many different locations, for example, the North Carolina woods where I grew up, and the ocean near LA, as well as New York. People have said, though, that they are all infused with an urban feeling, even when they are landscapes. I’m not sure how that happens, but you could say that Frank O’Hara’s great poem ‘Meditations in an Emergency’, 1957, catches the mood: ‘One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes—I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy’.

These works were made while you were locked down in New York. How did that influence them?

I think they benefitted from the isolation. In New York, life just collapsed, there was nowhere to go and time crawled by… The studio was – technically speaking – the same, but it felt very different…. And that affected what I was doing, and for me, it made the paintings talk about time.

Are there also political aspects to that difference?

I think so, yes. Lockdown made us realise together – collectively, wordlessly, like bees communicating in a hive – that we are vulnerable. I think that made it clear that a lot of work is needed to make things more balanced in society. I’m a Southern woman who was indoctrinated in Victorian values that resist being too explicit about such matters, but in a strange way, I think that’s in the show.

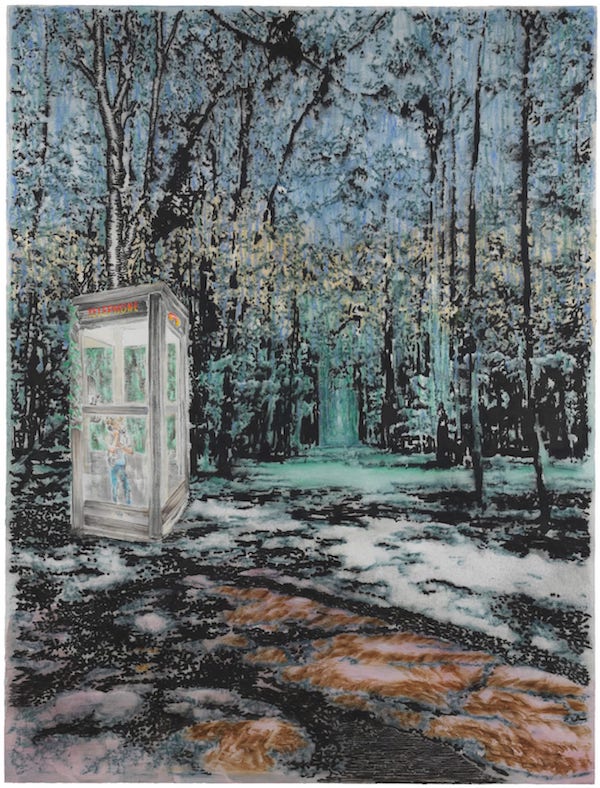

I was particularly struck by ‘area code 2019′. What’s happening there?

You could say that dropping a phone booth into this location makes no sense, but I’m drawn to phone booths as a plot device – miniature stages, places where superheroes go to get transformed… I started to take photos of them, but they’re vanishing – apparently, only four working phone booths remain in Manhattan. I got the idea of a small child – not really old enough to make a call – trying to use a phone booth at night in the woods, leaving you to wonder what the problem might be. It’s a mysterious painting of something you’ve never seen – yet feels familiar.

Finally, how did you get your unusual name?

My mother was immersed in poetry and got the idea of naming me after Dylan Thomas – but I turned out to be a girl. She somehow got the phone number of Thomas’s widow, Caitlin, rang her up out of the blue and asked her to name my daughter. She, unsurprisingly grouchy, asked what I looked like. ‘The ugliest baby you’ve ever seen’, replied my mother, ‘Crossed eyes, a lumpy head, a big strawberry birthmark and a tuft of red hair’. Caitlin said, ‘she sounds like an Ena. That means Ocean on Fire’. You wouldn’t choose to be a paradox, but I like the name now…

Paul Carey-Kent writes widely, including for Art Monthly, Frieze, World of Interiors and Border Crossings, and has a weekly column online at FAD Magazine. He is visual arts editor of the science-meets-the-arts magazine Seisma. Paul’s next curation is ‘A Fine Day for Seeing’ at Southwark Park Galleries (28 July – 29 August). You can find him on Instagram @paulcareykent and read a wider range of writing, including photo-poems, at Paul’s Art World.

Top Photo: Ena Swansea Central Park pond, 2019 – 152 x 274 cm Photo Courtesy Ben Brown