For Marc Chagall, a stained-glass window represented “the transparent partition between my heart and the world’s heart.” Stained glass is thrilling because it “has to live by the light which passes through it.”

Chagall created exceptional stained-glass windows for the cathedrals in Metz and Reims, Cordeliers chapel in Sarrebourg, the Hadassah synagogue in Jerusalem, Tudeley Parish Church in Kent and the UN headquarters in New York, as well as numerous other buildings, both religious and secular, in France and elsewhere, thus contributing to the twentieth-century renewal of sacred art. ‘Chagall. The Emissary of Light’ explores the importance of light and of stained-glass in his work by comparing preparatory drawings and finished windows, alongside a collection made up of paintings, sculptures, graphic works, and archives detailing the history of these commissions, his collaboration with master glassmakers and his free use of signs and symbols, in keeping with his humanist ideal of freedom and peace.

Models of stained-glass windows produced for buildings in the Grand Est region (Metz, Reims, Sarrebourg), neighbouring Germany (Mayence) and at the international level (Israel, United States, England, Switzerland) have been brought together for the first time and matched with a group of paintings, sculptures, ceramics and drawings from the collections of the Centre Pompidou, the Musée national Marc Chagall de Nice, from international museums and private collections. The exhibition shows the different stages of a stained-glass window from first drawings to its integration into the architecture and the alchemy that results from the association of the painter’s talent with the unique skills of the master glassmakers; in Chagall’s case, Charles Marq and Brigitte Simon.

In post Second World War France and the context of the renewal of sacred art, Chagall attempted to reinvigorate “exhausted humanity, during a time when the old religious or other ideals were withering and aspired to catch a glimpse of a ray of light which would illuminate a new meaning of life”. Convinced both of the necessity for a humanist ideal of liberty and peace and a supernatural power for the survival of any society or individual, Chagall’s work revived the polysemous nature of religious signs, their porous nature, and the possibility of a non-conformist narrative, freely scattered with personal recollections.

The exhibition enables the rediscovery of the significance of stained glass attained within an oeuvre that finds connections between art movements and techniques, the secular and sacred, Judaism and Christianity, shared and personal history, tradition and subversion, while remaining outside of any dogma. Above all else, for Chagall, stained-glass represents the best place for the apparition of invisible forces. As glass fuses with painting, joining forces with celestial beams and architecture, “something mystical … passes through the window”.

Meditations on religious art had been part of Chagall’s oeuvre from the off due to the place of religion in his Hasidic upbringing in Vitebsk (Russia). His later commissions for churches built on discussions about the relations between Judaism and Christianity held when he regularly attended, during his early period in Paris, the Thomist study circle organised by Roman Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain at his home in Meuden. Maritain encouraged the Dominican Friar Marie-Alain Couturier to find a place for Chagall in his projects to commission works from contemporary artists for churches.

Although he painted his first crucifixion in 1912, his ‘White Crucifixion’ from 1938 represented a significant point of transition for an artist who, while not a practising Jew, nevertheless felt intensely Jewish and was acutely aware of the rise of fascism in Europe. ‘White Crucifixion’ depicts the sufferings of the Jewish people in the image of a Jewish Jesus and led to a series of compositions featuring the image of Christ as a Jewish martyr that deliberately called attention to the persecution of European Jews in the 1930s. A few of his crucifixions of this period even equate his sufferings as an artist with the crucified Christ. Couturier’s request in 1949 for a commission in the baptistry of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce du Plateau d’Assy led to much soul-searching initially about creating work for a church. Jonathan Wilson says, “he both convened a rabbinical advisory board and wrote to Chaim Weizmann to ask if it was OK if he went ahead with the project”.[i] All was resolved in 1957 when his ceramic mural ‘Crossing of the Red Sea’ was installed with an inscription stating it to have been created ‘In the Name of the Liberty of All Religions’.

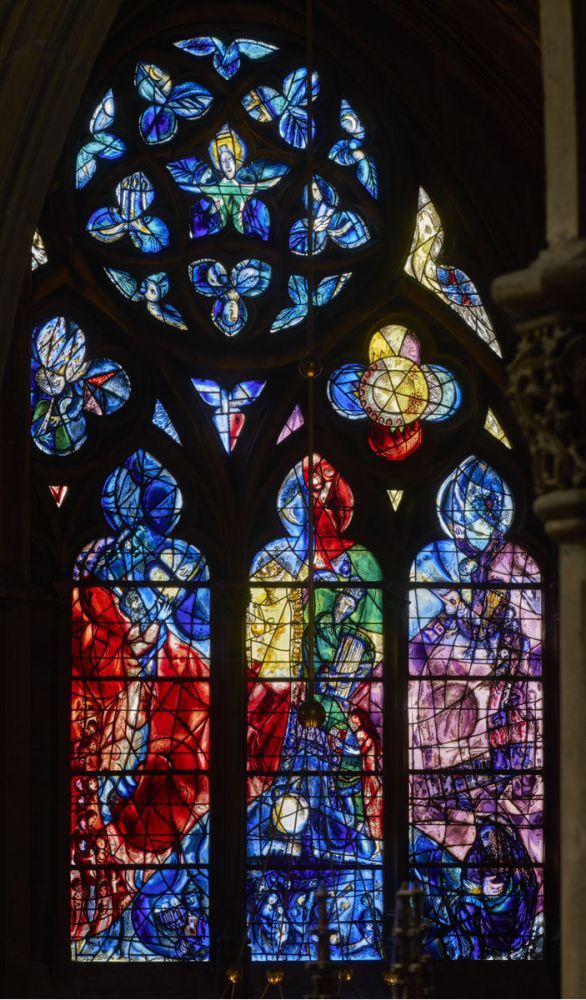

1957 was also the year in which he was commissioned to create windows on Biblical themes for Metz Cathedral. The Cathedral is nicknamed “God’s Lantern” and is renowned for the vast expanse of its stained glass – 6,496 square metres over twice as much as Rouen and three times as much as Chartres. Within this incredible expanse is glass from the thirteenth century all the way through to windows installed in the 1960s by Chagall and beyond. It is not simply the expanse of glass here which is impressive but also the range and variety that can be seen. Basil Cottle has noted that the glass here “is not stylistically co-ordinated; its assembly has been by slow growth, and many hands have participated, with many colours and iconographic schemes.” Yet, the “effect on entering the nave is dazzling: three tiers of windows, including the richly glazed triforium; extremely tall and acute-angling vaulting and apse windows, and a grove of slim clustered shafts receding eastwards into pools of colours.” [ii]

Chagall was inspired both by the Bible and his visits to Israel. Accompanied by his wife Bella and his daughter Ida, Chagall went to Israel first in 1931. The main reason for this visit was a commission he had received from the Parisian art dealer and publisher, Ambroise Vollard, to do a series of illustrations to the Bible. He travelled a great deal, painting and drawing in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and Safed. The country left a vivid impression on him, and back in Paris, the light and landscape he had seen were echoed in many of the etchings for his work, The Bible.

In 1951, the opening of a large retrospective exhibitions of his works in Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv prompted Chagall’s second visit. In 1957, he was again in Israel following the publication of his illustrations to the Bible. Vollard had died shortly before World War II and Tériade published the commission that had finally been completed in 1956. A second book of Bible illustrations was published by Vervé, also in that year. Chagall said that “In the East, I found the Bible and part of my own being. The air of the Land of Israel makes one wise.” For him, the Bible was “pure poetry, human tragedy.” He said that it “filled him with visions about the faith of the world” and that it inspired him so that he saw life and art “through the wisdom of the bible.”

Chagall also made a link between stained glass which comes alive “through the light it receives,” and the Bible which is “light already.” Stained glass, he suggested, “should make this obvious through grace and simplicity.” Jonathan Wilson noted that “Chagall became fascinated with stained glass after he had moved to the south of France in 1950”, writing that he was undoubtedly “seduced by the endless Mediterranean unfolding of colour-as-light and the possibility of capturing in glass the kind of spiritually charged, quasi-mystical, sometimes biblically inspired images to which he was increasingly drawn.” [iii] Indeed, Chagall spoke of light as being the material which creates stained glass. “The light is natural,” he suggested, “and all nature is religious.” Therefore, “every colour ought to stimulate prayer” and, “whether in cathedral or synagogue the phenomenon is the same: something mystical comes through the window.”

Chagall’s use of colour is also mystical, with “the yellow of revelation flooding the Tablets of the Law,” “the white of faith surrounding the cross”, and “the supremacy of blue in his work” indicating “the wisdom of overcoming bitterness and hatred.” [iv] At Metz Cathedral, we have the yellow of revelation flooding the Garden of Eden in Chagall’s 1963 Creation window for the triforium of the north transept while deep blues and reds characterise the combination of ecstasy and sorrow in the two ambulatory windows from 1960, which tell the story of the Jewish people in key episodes from Abraham to Jeremiah by way of Jacob, Moses and David. James Waller has written that here “Chagall is all curves and tonal flares,” his “modulation of tone, within the fabulously fragmented and flowing glass panes” lending “his colours a deeper, more smouldering dimension.” [v]

André Malraux summed this up when he wrote: “I cannot understand why stained glass, which lives and dies with the day, was ever abandoned. … Artists preferred the light. But the stained glass window, which is brought to life by the morning and snuffed out by night, brought the Creation home to the worshipper in church. … Stained glass eventually surrendered to painting by incorporating shade, which killed it. It was six hundred and fifty years before someone found a way of shading off colours in glass: Chagall.” [vi]

This exhibition is part of the celebrations for the eight-hundredth anniversary of the cathedral in Metz. It also marks a high point in the Centre Pompidou’s existence, celebrating its tenth anniversary.

Chagall. The Emissary of Light, Centre Pompidou-Metz, extended until August 30, 2021

[i] Jonathan Wilson, Rhapsody in Blue in Tablet, January 2011 – https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/rhapsody-in-blue.

[ii] B. Cottle, All The Cathedrals Of France, Unicorn Press, London, 2002.

[iii] Jonathan Wilson, Rhapsody in Blue in Tablet, January 2011 – https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/rhapsody-in-blue.

[iv] Hilary Hope Guise, Marc Chagall and the Supremacy of Blue, 2012 lecture – http://www.summerschool.uct.ac.za/marc-chagall-and-supremacy-blue.

[v] James Waller, Of Glass and Gold II: St Etienne, Notre-Dame and the Stained Glass of Marc Chagall, Carmelite Library, Victoria, Australia, November 2013 – http://thecarmelitelibrary.blogspot.com/2013/11/of-glass-and-gold-ii-st-etienne-notre.html.

[vi] Jonathan Wilson, Rhapsody in Blue in Tablet, January 2011 – https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/rhapsody-in-blue.