The first exhibition in the UK exploring sin in art will be staged at the National Gallery this spring. ‘Sin’ will bring together paintings from the National Gallery’s collection dating from the 16th to the 18th century with loans from important private and public collections including modern and contemporary works by Andy Warhol, Tracey Emin, and Ron Mueck.

The exhibition ‘will lead to much discussion and reflection on the meaning and imagery of sin – Dr Gabriele Finaldi

Dr Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery, says the exhibition ‘will lead to much discussion and reflection on the meaning and imagery of sin.’ The curator of ‘Sin’ Dr Joost Joustra, The Howard and Roberta Ahmanson Fellow in Art and Religion has said: ‘Sin invites visitors to reflect on a fundamental concept that pervades our lives and history, but also to marvel at the ingenious ways artists have addressed the subject across time.’

I explored with Joost the genesis, significance and potential impact of this exhibition which has been characterised in the press as provocative, tempting and entertaining.

JE: Roughly one-third of the paintings in the National Gallery’s collection of Western European art are of religious subjects and nearly all of these are Christian. Sin is an omnipresent theme within these paintings but this is the first exhibition in the UK to coherently explore this theme. Why is the Gallery exploring this theme now and why has the Gallery decided to explore its collection in a way that differs from previous exhibitions that explored aspects of devotional art?

JJ: This is a project that originated when I started as Howard and Roberta Ahmanson Fellow in Art and Religion at the National Gallery. It is an opportunity to bring different themes and schools of art together and represents a new way to explore the collection.

Sin was a subject hiding in plain sight within the collection and one which, once highlighted, others at the National Gallery could see had real potential. Sin is a vast theme with many interesting and very varied visual explorations.

People have specific expectations of an exhibition on this theme, including paintings of Adam and Eve. But such pictures are simultaneously risqué depictions of nude figures. It has been interesting bringing together paintings that both confirm and challenge expectations.

JE: To what extent might these changes reflect wider changes in approaches taken by curators towards Christianity and religion more generally? For instance, the RA’s decision last year to bring together works by Michelangelo and Bill Viola simply because both explore the big life issues that religions also explore and do so using religious imagery.

JJ: The Michelangelo/Viola exhibition does show a kinship with my thinking, particularly as I am interested in showing how subjects from the distant past can be connected with contemporary thought and works of art. These connections show that artists remain interested in the same questions, which are universal issues. Curators of collections containing art from the Christian tradition need to ask how to make pictures of Christian images or subjects interesting to audiences that don’t engage with these issues so much anymore and one way to do so is to show connections to contemporary art.

JE: Although one-third of the paintings in the collection are of religious subjects, many of those visiting the collection will not be religious. To what extent do you find Christian imagery and concepts engage or are understood by those for whom religion is of minimal significance? What strategies are used in an exhibition such as ‘Sin’ to counter issues arising from religious literacy?

JJ: The paintings to which you refer were originally made for both religiously literate and non-literate audiences. Such art is often referred to as the ‘Bible of the illiterate’, as a result, has always been didactic. However, as with a work such as Michelangelo’s ‘David,’ people flock to see it as it is iconic, beautiful and an example of an artist mastering his material. People may also recognise that they are seeing a depiction of an Old Testament King but, if not, their initial attraction to the work can be used to draw them in and tell them the story. They will be interested in the story because they are already interested in the work.

In this exhibition the labels for the work will have explanations of key concepts described in an approachable way. The catalogue will be different from the norm in that it will include additional works from the collection and works not in the exhibition in order to provide a broader introduction to the theme of sin in art.

JE: How does the National Gallery address the exhibiting of devotional art that is predominantly Christian, when those visiting are people of faiths other than Christianity?

JJ: People are still drawn to these artworks for a whole set of different reasons. People from all over the world from a very wide range of different backgrounds still like to come and look at the paintings in the collection.

The exhibition will encourage different responses and perspectives and may prompt people to think about similarities and differences in the understanding of sin within different faiths. For example, in Christianity, the story of Adam and Eve is called ‘The fall of man’ while, in Judaism, the interpretation of this story is less severe. People will bring different understandings to the experience of viewing the paintings; however, there is, I think, an elemental understanding of right and wrong to which everyone can relate.

JE: In what ways does the exhibition ask viewers to define their own meaning of ‘Sin’?

JJ: Brueghel’s ‘Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery’ is a key image in this regard. Christ says, ‘He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone.’ People who are pointing fingers and accusing another stop and start thinking about where they are in the story and where they stand. This is an evocative story and image which still makes people stop and think.

JE: How is the idea that art can blur the boundaries between our modern categories of religious and secular explored in this exhibition?

JJ: What we call now secular is historically difficult as the Church, in the past, was fully interwoven into society. However, some ideas that found their most eloquent expression in religion existed before and have continued to lead their own life since.

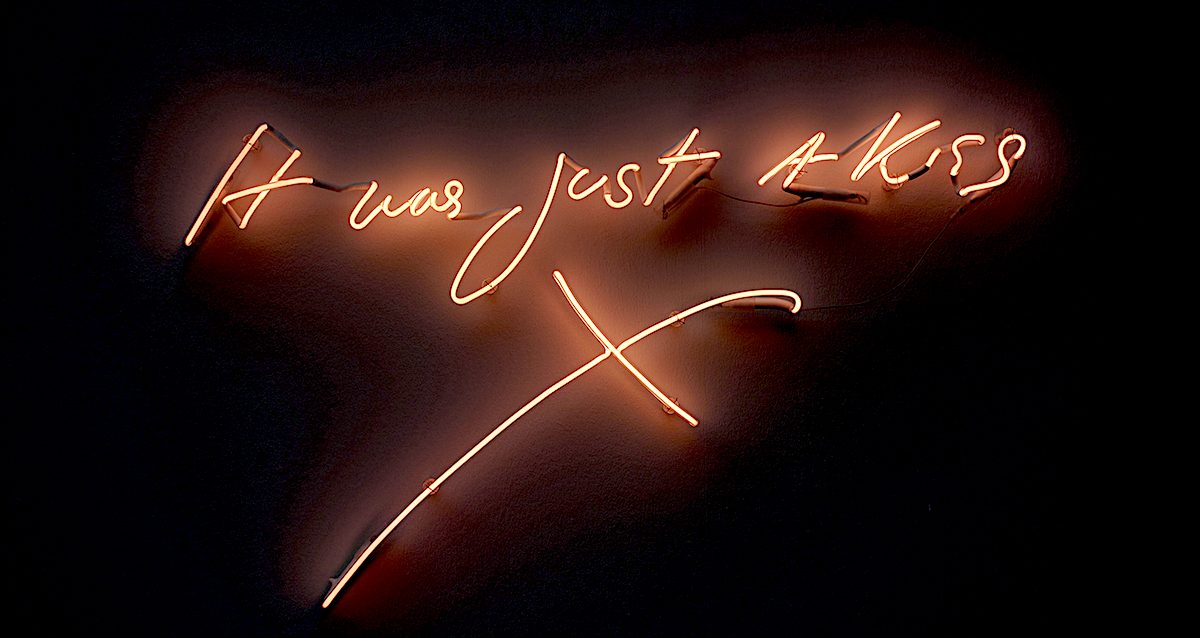

Tracey Emin’s ‘It was just a kiss’ is an example of blurred boundaries. This is an ambiguous image that contains themes of confession, admitting and atoning. It can be read as a modern confession; part of a story told to a priest in a confessional. However, it could also be related to the story of Christ and Judas with betrayal coming by a kiss. Just a kiss! It seems like a very simple statement but has significant ambiguity and depth. Emin puts us on the other side of the confessional and makes us think about what these themes may mean in our own lives. Is she in this work wanting our absolution, while also wanting to challenge us to confess too? The “muteness” of the work means that it never gives away everything it contains, while we are also able to project our ideas and interpretations onto it.

JE: The exhibition brings together works of art that span centuries – from Bruegel and Velázquez to Andy Warhol and Tracey Emin. It is to be expected that the more modern or contemporary images display an ambiguous representation of sin, but where is ambiguity to be found in earlier images that were created as part of Christendom?

JJ: Bronzino’s ‘An Allegory with Venus and Cupid’ is a mysterious picture that was never meant to be about a single thing. It is a mother and child image but one which is erotically charged. There are allusions to Adam and Eve including a golden apple and a background figure with a serpentine torso. This is a very ambiguous image from a master of allusion which makes us think but without giving away all the answers. People don’t look and think of this as a religious image but it does still have something to say about religion.

I have placed two Lucas Cranach paintings next to each other; Eve and Venus. If one were to look without context, they would seem almost interchangeable. Both address the theme of temptation but explore different levels of temptation. The idea of temptation underlies The Fall, with temptation depicted in the nude body. Is the image moralising or sinful? Where does the boundary lie? This is a question posed by such artists.

JE: What is entailed in being Howard and Roberta Ahmanson Fellow in Art and Religion at the National Gallery and how does this wider role mesh with the curation of this exhibition?

JJ: This is different for every Fellow. It is a three-year Fellowship which aims to bring religious images painted many centuries ago into the present by showing their contemporary relevance. ‘Visions of Paradise’ was an exhibition curated by the first Fellow, while others have made films or written books. For me, the theme of sin was the way of engaging with the collection. I came with an idea about sin as a theme. However the idea has developed massively through being here.

JE: From ‘Seeing Salvation’ to `Devotion by Design’ to ‘Sin,’ how has the approach taken by the National Gallery to the researching and exhibiting of devotional art changed in recent years? Why do you think such exhibitions remain popular and of interest in a society that has become both more secular and more diverse in terms of faith commitments?

JJ: Art and religion together form a key pillar of research at the National Gallery. There is not a specific strategy but there is recognition that the religious aspects of the collection are a story worth telling. We have a beautiful collection of images that tell these stories and so the possibilities for exhibitions are endless.

People today are much more likely to engage with every subject in multi-faceted ways. I love Instagram, for example, because it brings the world’s visual culture to you in seconds. Today there are less rigid ways of dealing with themes and topics and this approach brings change and surprises. This includes a recognition that the category of religious or Christian art encompasses much more than altar-pieces or icons or panels for private devotion and can be found in a lot of work by contemporary artists and in unexpected places.

One of the surprises for me has been the recognition that sin is a subject I’ll be working on for the rest of my life; it is a never-ending project.

‘Sin,’ 15 April – 5 July 2020, National Gallery, Room 1