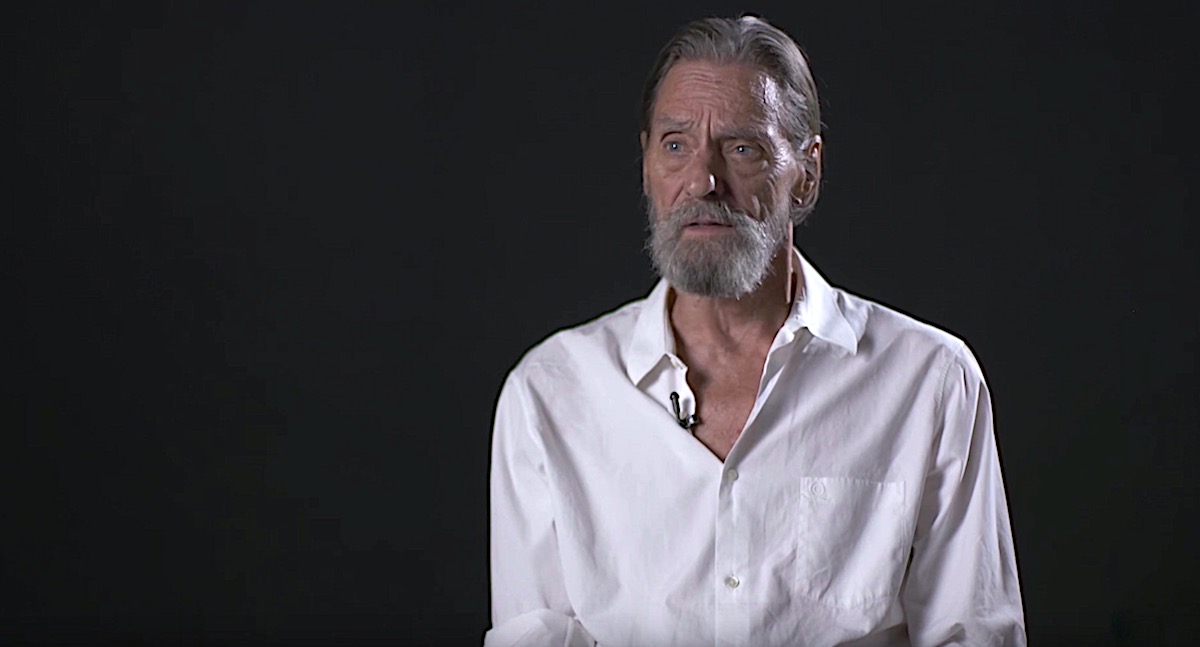

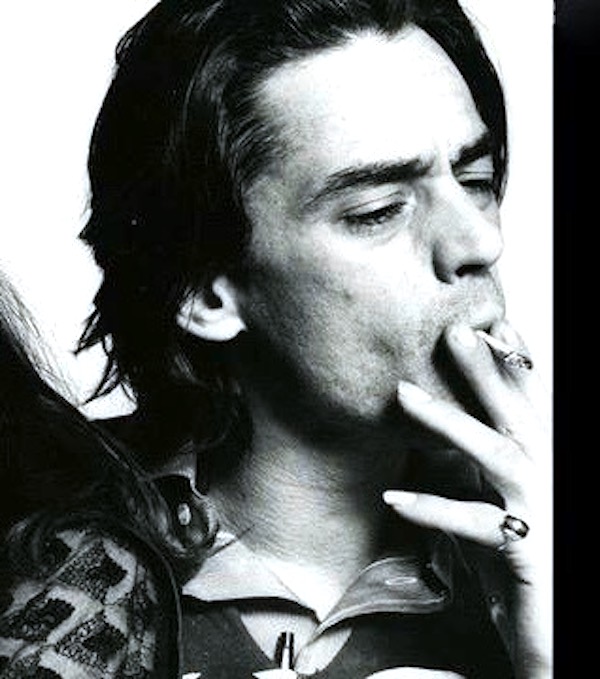

ULAY, who died last week at 76, was tall, handsome, clever, charismatic. In the 1980s he was also half of the world’s golden couple of performance art Ulay & Abramovic.

I met him first sometime in the early 1980s, before Marina Abramovic’s career skyrocketed to eclipsed his own

In 1988 the lovers’ 2500 km walk, from opposite ends, along the Great Wall of China, & filmed by Scot, Murray Grigor, was initially to end in marriage but concluded with separation. The following year I went to visit Ulay at his home in Amsterdam where he lived much of his life. By then, he had a new partner who was pregnant. In 1998 he came to Glasgow for the first time, to Tramway to present a major retrospective of their performance video installations 1976-80, where I interviewed him on Valentine’s Day, appropriate for what was then still a love story, their later court case battle still far in the future.

Despite jet lag – having arrived directly from LA (and BA had just lost part of an artwork), he was again charming, soft-spoken, gentle. “Artists are usually rather egotistical people. They don’t usually work together, but we decided to try. It was beautiful. We had a unique, wonderful relationship. Marine left her Yugoslavian life behind. We were poor and lived very simply in a Citroen police van like nomads with the minimum of possessions. What we did have was our relationship and our work. It was perhaps our happiest time.”

The 1998 Tramway show was impressive, including 17 life-size, full length, unedited, uncut pieces from a 12-year span when, in their thirties, young, skinny, often naked, they twist and turn, fight, cut, run into walls, pillars – or each other. They aimed to become a single artistic entity. Ulay remembered, “The video quality is poor because video technology was at an early pioneering stage then. I’m from the sixties – of an anti-aesthetic orientation – so I don’t mind blur. I like it. It’s just fine.”

How can so much flesh be so cerebral? “We had only one rule: never be pathetic. We took our clothes off not for 1970s naturalism but for the sound of flesh colliding,” Ulay explained to me. “We never rehearsed and the pieces had no predictable end. We never knew how far we would go, how long we could go on. It was all about endurance; heavy endurance in which we relied on our physical and mental strength. Who creates limits? I was happy to create my own. The sole means and materials were our own bodies and minds. Sometimes I quit; sometimes Marina. Her physical metabolism is slower than mine. I couldn’t fast as long as Marina. My maximum is 21 days, Marina 40 days. We never cancelled a performance – fever, dysentery – we still did it. As we never rehearsed, neither we nor the audience knew what to expect. That’s why the communication was so powerful, the work so convincing.”

Trust played a key role. The famous piece from 1980, where Ulay’s taut bow & arrow arrow points at Marina’s heart is crucial. Ulay explained, “The performance lasted 4 minutes. After that I couldn’t trust my fingers. It’s very symbolic piece for our relationship.”

They tried everything: slapping each other’s faces, (20 minutes), screaming (15 mins), kissing, their long hair tied together back to back (17 hours.) In the 1970s, this was emotionally very difficult for an audience. The reality was quite different from looking at videos. Marina sitting among raw, oozing, bloody, stinking butchers bones at the 1997 Venice Biennale is a quite different experience to a sanitized video, I can tell you! Performance must be seen. The videos lack the charge of fear, panic, repulsion, sympathy which reality brings.

Back in 1998, Ulay opined “The Internet is totally remote form of communication. Totally safe. It cuts out sensations and senses. There is no touch. No smell. No taste. Real experience is the key thing. With live performance you have to travel; move.”

Ulay told me, “There’s an important sound rhythm I didn’t expect.” He believed, “The body is all there is, it’s all we have. If you get sick, the world changes. You deal with that as long as you live.”

Years later, Ulay did indeed ‘deal with that’ by making a film when he was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. The 2011-13 documentary, Project Cancer, chartedhis treatment. After chemotherapy, Ulay went into remission but continued to smoke.

While the couple’s early work was violent, passionate, aggressive, by the 1980s, a more passive silent aspect took over. Between 1981 and 1987, the pair made 22 performances of Nightsea Crossing where they sat silently across from each other seven hours a day, which prefigured Marina’s 2010 MoMA triumph. But the pressure of work grew. In 1984 Ulay’s mother died, and things deteriorated.

Later he said, “We became over-exposed. Idols. She enjoyed becoming a star. It is something I do not envy. It’s far away from my intentions, wishes, desires, it went to her head.”

After their break-up Ulay returned to his first career, photography, exploring new techniques of colour reversal film, massive Cibachrome prints, giant Polaroid portraits, fragmented screens and then 35mm film.

But the most notorious Instagrammed/You Tubed event took place in 2010 during Marina’s major New York Moma exhibition. Here she repeated one of their performances, sitting all day long, never moving, staring – not at Ulay as in the 1980s, but at members of the public who lined up for this marathon. One day Ulay turned up to sit opposite. Their emotional meeting has been viewed nearly 18 million times on YouTube.

In 2015 Ulay sued her for £200,000, for withholding money owed to him and not fully crediting his part in their artworks. She paid up. However, the two became good friends again, participating in a 2017 film, The story of Marina and Ulay, which charted the course of their relationship. “The breakup was heartbreaking for both of us. We were both hurt—no communication for 20 years. Then nasty disagreements or whatever from the past, we dropped,” Ulay said in the film. “That’s a beautiful story.”

By a turn of fate in the last dozen years Marina came to buy a house near ours in Upstate NY, and I got to know her better, wrote about her exhibitions and performances for the Financial Times, went to her 60th B-day, met her for dinner. Sadly I avoided the subject of Ulay. When he died last week, in Ljubljana, the Slovenia home to his graphic designer wife, I deeply regretted that. But he, like Marina, seemed indestructible. I assumed this charismatic golden couple would live forever.

Words: Clare Henry © Artlyst 2020

Watch Video Below