2012 is turning out to be a massive year for the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch – with the recent landmark auction of a version of “The Scream”, a new exhibition at Tate Modern opening next week (Until 14 October) and a show of his graphic works at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (until 23 September).

Munch is primarily associated with his seminal work “The Scream,” and much of his career remains obscure, even among those who study Modern European art. However, the painter had prolific output throughout his life, and when he died, a collection of 1,008 paintings, 4,443 drawings, 15,391 prints were discovered in his home (in addition to woodcuts, etchings, photographs, and more). It seems a bit sad that a man so devoted to his art that he referred to his paintings as children should be remembered for just one work. Perhaps the increased profile of the artist through the record-setting auction and the Tate exhibition will shed some light on the lesser-known works.

Kynaston McShine, who curated the MoMA exhibition, refers to Munch’s iconic status in popular culture, but also laments the lack of understanding of the depth of the artist’s career and oeuvre.[1] The description of “Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye” on the Tate Modern website ends with “So you think you know Edvard Munch? Think again” – calling the public to reassess their image of the artist by understanding the larger output of work.[2]

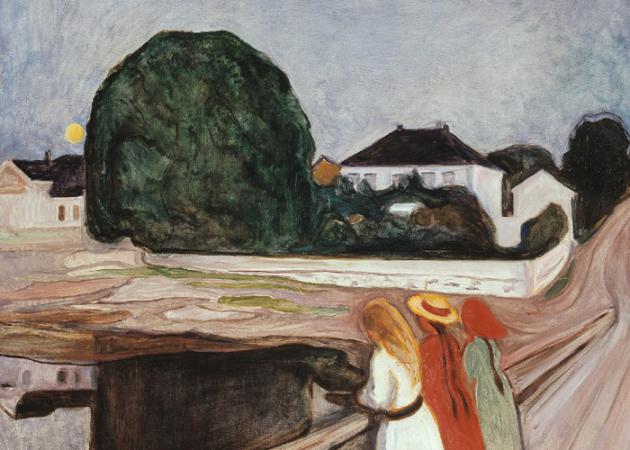

Edvard was a student of Christian Krohg, a Norwegian naturalist painter, but it was the influence of the works of Gauguin and van Gogh, who he was exposed to in Paris, that were more formative in the development of his style. Being educated in a traditional and academic style did not suit Munch’s needs of expression. According to Arthur Lublow’s article in the Smithsonian Magazine, “Munch quit the class of an esteemed Parisian painting teacher who had criticised him for portraying a rosy brick wall in the green shades that appeared to him in a retinal afterimage. In ways that antagonised the contemporary art critics, who accused him of exhibiting ‘a discarded half-rubbed-out-sketch’ and mocked his ‘random blobs of color,’ he would incorporate into his paintings graffiti-like scrawls or thin his paint and let it drip freely.”[3] Though Munch ultimately rejected naturalistic rendering of his subject matter, the paintings seem remarkably real due to the emotional charge granted to each figure and even the setting.

Munch’s personal life was certainly tumultuous, and it can be argued that his artistic production acts as a self-portrait. Both Munch’s mother and younger sister died from tuberculosis early in his life. His sister wanted to be placed in a chair instead of her bed as she was dying, and this event seems to have deeply influenced young Munch who kept the chair for the rest of his life and frequently revisits the motif of a sick young girl. Munch himself suffered from tuberculosis as a child and never fully recovered his health. Of his other siblings, one sister was confined to a mental hospital and his brother died of pneumonia at the age of 30. Only Edvard and one sister survived well into adulthood, and both remained unmarried. Edvard’s father was a physician, and perhaps due to his inability to protect his family from disease both physical and mental, he held a strong fascination with the “next life,” which would certainly be disconcerting for a child. Munch’s father died in 1889 leaving Munch full financial responsibility for the family.

In addition to themes pertaining to illness and his family, Munch often utilised his paintings to work through deeply rooted concerns with dominant women. Millie Thaulow was the wife of a distant cousin, and it was with her that Munch had his first sexual encounter at the age of 21. He was deeply enthralled by Millie and absolutely devastated when she ended the relationship two years later. Though this elicit relationship occurred relatively early in Munch’s life, the feelings for Millie remained with Munch for much of his life, affecting his other relationships with women. Beginning in 1898 Munch had a turbulent relationship with Tulla Larsen in Kristiania (now Oslo). Tulla desperately wanted to marry Munch, who though spent a considerable amount of time with her, was not attracted to Tulla and did not want to get married. The image of a femme fatale in Munch’s work is undoubtedly a result of these two relationships.

Munch’s works embody the existential concept of ‘angst’ defined as “the dread caused by man’s awareness that his future is not determined but must be freely chosen.”[4] The responsibility of determining one’s own fate is overwhelming, especially in one faced with depression and anxiety such as Munch. He stated: “My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder… My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.”[5] Munch intentionally left his paintings looking unfinished to better express emotion instead of covering the feeling imbued within the work with a glossy finish. In addition to depression and anxiety and poor health, Munch also battled with alcoholism. Ultimately, Munch received treatment in a sanitarium where he resumed some stability, but lost much of his creativity and vigour. The production of work after 1909 is not as exciting and innovative as the previous works which calls to mind the question of the connection between madness and creative genius.

The Tate exhibition opening later this week is the newest in a long sequence of exhibitions focusing on the work of Edvard Munch. Other highly respected venues, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Royal Academy in London, and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm have celebrated various facets of the artist’s career. Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye aims to set itself apart by examining the Munch’s relationship to modern life and also by exhibiting works in film and photography that are a lesser known part of his oeuvre. Throughout his career, Munch revisited and reworked several themes that can be seen over a long period of work. At the end of the exhibition, the Tate focuses on Munch’s degenerating eye sight in the 1930s as the final phase of his career. The loss of sight becomes an aesthetic quality as well as the subject of the late works and questions what a visual artist can be without the power of vision.

Edvard Munch is one of the best known names in twentieth-century art, but there is more to the man and his career than the single image of “The Scream.” Looking at other media and Munch’s personal history will bring a fuller and more well-rounded understanding of the artist and perhaps a greater appreciation for his art. Words: Emily Sack © ArtLyst 2012

Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye will be on display at Tate Modern from 28 June to 14 October 2012.

Visit The Tate Modern Exhibition Here

[1] http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/munch.html

2] Tate Modern

[3] Smithsonian Magazine (see link above)

[4] The Free Dictonary.com

[5] Smithsonian Magazine (see link above)