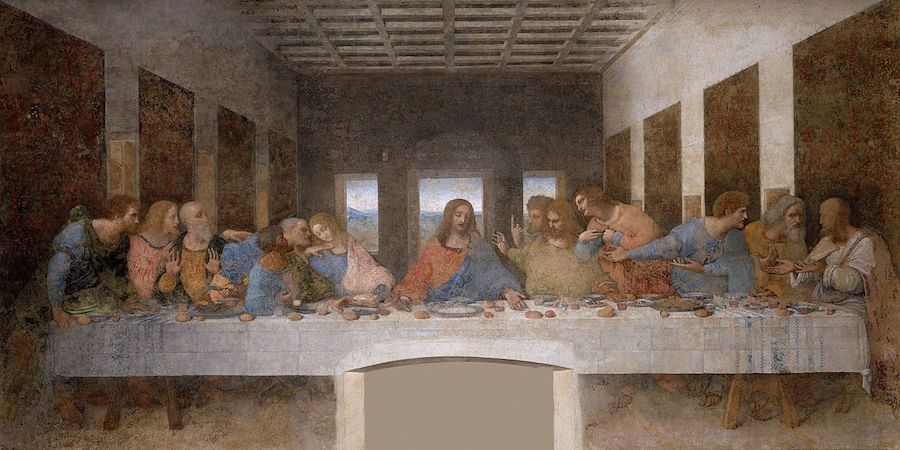

Leonardo’s Last Supper is back on view at the RA. Or at least a copy of it is, made by his pupil Gianpetrino. And to celebrate the event, there’s now a website devoted to it – the copy not the original. You can find it Here

The Last Supper offers the culminating moment in a drama – ELS

Anybody who has seen the original at Santa Maria dell Grazie in Milan can testify to how disappointing the experience is. It is the only significant, multi-figure composition by the artist that survives. He attempted one other but characteristically didn’t finish it. The article devoted to the painting in the Encyclopaedia Britannica waffles on about how wonderful it is, telling you that the work “has become part of humanity’s common heritage and remains today one of the world’s outstanding paintings.” It depends what you mean by the word ‘remains’. What you see today is a battered ghost of what the artist intended. As Britannica also tells you: “[Leonardo] bypassed traditional fresco painting… in favour of another technique he had developed.” It didn’t work, and the painting soon started to fade. It has been considerably messed about with since. It was painted between 1495 and 1498, and by the middle of the following century, it was already being described as a ruin. At one point a door was punched through the wall on which the composition is placed, removing Christ’s feet, once visible under the table at which sits. Over the years various misguided attempts were made to restore the work. The most recent of these, and pretty certainly the best, took place between 1980 and 1989. As the Britannica article ambiguously admits: “[This] restored the work to brilliance but also revealed that very little of the original paint remains.” In other words, what you get when you go to see it is an elaborate example of scholarly wish fulfilment. The word ‘brilliance’, in either of its possible senses, can’t honestly be applied.

The Last Supper/ Il Cenacolo/ L’Ultima Cena 15th-century mural by Leonardo da Vinci at refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy

If you want to get any real idea of what Leonardo actually intended, you do better to go and look at the same-size copy at the RA, which was made, very close to the original date of creation, by a contemporary who was a close associate of the artist, using a more conventional, less experimental technique. We know, in any case, from the history of Leonardo’s own career that, brilliant as he was, he easily tired of the artisanal labour of making paintings, and as often as not, dumped the job onto one of his associates and veered off into making something else. If you want ‘original Leonardo’, in the sense of something made by the artist’s own hand, you probably do better to go to his numerous drawings. A large number of these survive in good condition in the British royal collection and are occasionally on view.

Oddly enough, the situation I’ve just described: having brilliant ideas but running away from making the actual physical thing, has been rather typical of some of the most lauded creators of today’s contemporary art. Those concerned don’t draw nearly as well, nor think as originally as Leonardo did, but they share the same reluctance to undertake the physical slog of making what they have thought up. I suspect, however, that living as he did in a much more artisanal society. Leonardo was never quite so self-righteous about it.

Meanwhile, there is the copy at the RA, ready to tell us more about Leonardo’s intentions than we can get from the battered, exhausted, frequently titivated by other hands original. Oddly enough, this process is maybe more efficiently done if the modern spectator is not just at one remove but at two. One of the fascinations of the artsandvulture.google.com web site is that invites us to look, not just at the painting as a whole, but at numerous details. The Last Supper offers the culminating moment in a drama – one which, as I have already said, features numerous participants, each one of them adroitly characterised. Jesus, at the centre, has just told those present “One of you will betray me”. How will they variously react? Judas nervously clutches his bag of silver, payment for the betrayal. Overturned under his wrist is a salt cellar, spilling out its contents, a symbol of tragic events still to come. The other disciples, each one adroitly characterised, display a range of reactions to Jesus’ words.

While the RA galleries, at this moving-hesitantly-away-from-corona-virus moment, maybe quieter than they usually are, it’s hard to pay this kind of derailed attention to a painting when one is a member of even a small gathering. Being there in person offers, yes, a collective experience. But, dare one say it? The experience concerned often gets in the way of actual close observation. How many of the details do we remember, once we move away from the work concerned? The truth is that the complex narrative Leonardo clearly wanted to deliver may now be offered in more efficient form, not merely by a good quality, well-preserved copy of his ruined original, but by this copy examined, not in person, but at leisure and in detail, on a computer screen.

Further Reading

Leonardo’s Last Supper (ca. 1495-98) in the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, was commissioned by his patrons Duke Ludovico Sforza and Beatrice d’Este. The painting represents a scene from the Gospel of John, chapter 13, verse 21, when Jesus announces that one of his Twelve Apostles will betray him. Historically the work was attributed to Marco d’Oggiono (c.1467-1524) and this was the artist named linked to the copy when the Royal Academy bought the painting. More recently it has been attributed to Giampietrino, a pupil of Leonardo although there is also the suggestion that Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467-1516) may have worked on this copy as well. This copy was privately owned until it was sold to a Carthusian monastery in Pavia in 1591. The copy remained in the monastery until about 1793 when, following the Austrian suppression of the Carthusian monasteries, it was sold. It was then on display in the Brera Academy in Milan for many years before being sent to England in 1817 to be sold. It took several years before the RA actually bought the painting. According to Henry Fuseli it was ‘rescued from a random pilgrimage by the courage and vigilance of our President who was by then Sir Thomas Lawrence.’ The Royal Academy bought this copy of the Last Supper for six hundred guineas from an H. Fraville in 1821.