Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Sale will offer two pieces from the collection of renowned publisher and art collector, Benedikt Taschen. Martin Kippenberger and Jeff Koons, leaders of the New York and Cologne art scenes, both controversial and ambitious artists, first met in Cologne in 1986, where Taschen’s publishing empire was founded a few years earlier. Through Untitled and Louis XIV, Kippenberger and Koons, who possessed strong mutual respect for one another, were both taking the guise of art history to portray themselves, the first one as the greatest of all 20th century painters, Pablo Picasso; the second, as the royal figure of the ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV.

Martin Kippenberger’s Untitled, the most famous work from his acclaimed self-portrait series which is recognized as the most important in the artist’s oeuvre belonged to Koons before being in Taschen’s collection. With an estimate of $15-20 million, this anti-heroic self-portrait could break the artist world auction record of $22.5 million which was achieved last season at Christie’s for a work from the same series. As to Koons’s dazzling portrait of the powerful Louis XIV, is estimated $10-15 million.

Ever since my early childhood, I was fascinated by painting. As a young boy, my first loves were probably major surrealist painters like Magritte, Dalí, and Miró. I started collecting art in 1985. At the time I lived and worked in Cologne, Germany, which for nearly a decade was the epicenter of contemporary art in Europe. Artists from all over the world, both established and up and coming artists, were showing in Cologne. Art galleries opened all over the place. Every important artist of this generation (with the exception of Basquiat) had major shows here: the German artists Martin Kippenberger, Albert Oehlen, and Günther Förg, but also the Americans, like Christopher Wool, Mike Kelly, Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, Robert Gober, and Cindy Sherman, to mention just a few whose careers I watched most closely.

My personal heroes were Albert Oehlen, Martin Kippenberger, and Jeff Koons. Our first book on this generation of artists was released in 1987 and simply called “Contemporary Art”. Then in the early 1990s, we published their first monographs and without a doubt these artists had a profound impact on the profile of the publishing house. Besides our professional relationship, a number of these artists became close friends and it is fair to say that I wouldn’t be the person I am today without them. I was very, very lucky to be in the right place at the right time and I am extremely grateful that this generation of artists became such an important part of my life,” declared Benedikt Taschen in an interview with Brett Gorvy, Chairman and International Head of Post-War and Contemporary Art.

Kippenberger, Untitled, 1988

Untitled forms part of Kippenberger’s most iconic series of large-scale, mock-heroic self-portraits painted in the summer of 1988. In Untitled, the then 35 year old artist presented himself not as the confident, powerful master artist despite his recent inclusion on the list of invitees to the 1988 Documenta, which had finally elevated him the long desired international recognition. Instead, Kippenberger consciously opted for another type of portrayal, which was deeply engrained in his practice: the artist as the imposing anti-hero, exposing human and artistic imperfection as well as a real fear of failure. Untitled emerge as a direct result of Kippenberger’s contemplation of the well-known 1962 photograph of Pablo Picasso taken by photojournalist, David Douglas Duncan. Exuding an overwhelming abundance of confident masculinity, Duncan’s photograph of the eighty-one year old artist exhibits an esteemed amount of buoyant virility. Parodying his famous antecedent, Kippenberger playfully subverts the machismo associated with the genre of self- portraiture in his fleshy, underwear clad depiction. Untitled mocked the artist’s supposed heroic self-image by depicting him as equally triumphant and trifling. The concept of the mock-heroic is central to Untitled, as rather than defying the notion of self-portraiture as an insight into the artist’s self, Kippenberger embraces it, publicly displaying his most private emotions while portraying himself as the fallen hero.

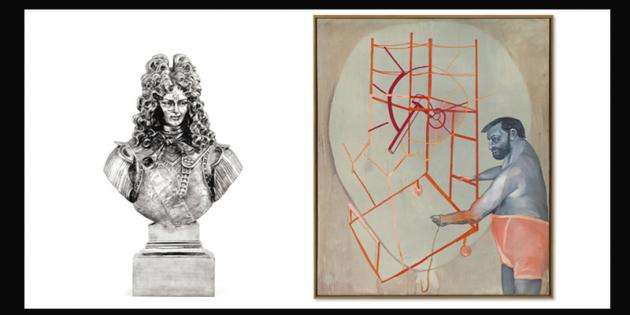

Jeff Koons, Louis XIV, 1986

Jeff Koons’ Louis XIV is an imposing, impressive sculpture: its gleaming surface accentuates the Baroque forms of the tumbling torrents of hair, the floral incisions on the cuirass, the lace of the cravat. Meanwhile, the monarch’s sneer of cold command lends it an impressive, authoritative weight and gravity. Executed in 1986, Koons’s sculpture clearly harkens back to the age of the Baroque, to the long reign of Louis XIV of France As King of France, Louis XIV, the so-called ‘Sun King’. At the same time, it is a contemporary masterpiece, an emblem of post-modernism, as is demonstrated by the fact that, of the three casts and artist’s proof, examples are held by the Dakis Joannou Foundation and the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. The casts have featured in a range of publications and exhibitions, including Koons’ celebrated and controversial show at the Palace of Versailles, the royal residence which was at its epitome under the reign of Louis XIV. Louis XIV forms a part of the Statuary series; these ranged from the Baroque to the kitsch to the contemporary, from the supposedly eternal to the resolutely ephemeral, each subject unified through its being reincarnated in the same material. The quality of the steel is dazzling: it is so reflective that it creates a range of ever-shifting visual effects. The steel of the armour is smooth; the face has been created through undulating forms that have the near-liquid appearance of mercury, contrasting with the more textured finish of the hair itself, results of Koons’ now-legendary perfectionism.

The Luxury and Degradation of Jeff Koons and Martin Kippenberger

Jeff Koons’ stainless steel statue of Louis XIV made in 1986 and Martin Kippenberger’s untitled self-portrait from 1988 are two works of art that, at first sight, seem to be light years apart from one another. One is a shiny, elaborately hand- crafted image of eighteenth century elegance and luxury in the form of a metallic bust of the Sun King, the other is a vast, deliberately sloppily-painted oil portrait of an overweight, middle-aged man bumbling around in his underpants in front of a clumsily drawn red sculpture while holding onto a giant balloon. On almost every level, each of these distinctive works seems to be the opposite of the other. Indeed, the same might also be said for the two creators of these, now famous, works of 1980s’ art. Jeff Koons, an American, born in York, Pennsylvania, is a slick, clean-cut, always immaculately turned out and ingratiatingly polite, artist, whose impeccably organised oeuvre consists almost entirely of a neat sequence of carefully delineated series, each of which is itself made up of distinct, painstakingly planned and individual works of art executed to the highest standards of craftsmanship and a pristine degree of perfection. By contrast, Martin Kippenberger born in Dortmund, Germany, was a restless, bohemian, bon viveur who emerged out of the Berlin club scene of the late ‘70s with an art that seemed to both revel in and actively celebrate his own, very human, failings. Often drunk, always on the move, Kippenberger’s rapacious way of living and working was founded largely on impulse and spontaneity. In addition, his uncompromising willingness to be rude, coarse or even boorish in the name of truth, art or just a good laugh, led to him making as many enemies as admirers before his premature death from drink-related cancer in 1997. Kippenberger’s oeuvre comprises an almost endless production-line of work made in a whole range media and with an always whimsical, almost desperate sense of urgency.

Yet, in spite of this, Kippenberger’s Untitled of 1988 – probably the greatest of his many self-portraits – and Koons’s sumptuous Baroque statue of French royalty in the form of a metallic, industrially manufactured knick-knack, are two works that, like the artists themselves in fact, have far more in common than surface appearances might suggest. Both works, for example, are proxy mock-heroic self-portraits that, with a shared sense of knowing detachment, address and reflect upon what, in the 1980s, was, a new and vastly inflated art world in which the status and the identity of the art object and the role of the artist within it was fast changing.

Among the first artists to understand this rapidly changing economic landscape in the art world of the 1980s, Koons and Kippenberger responded to the new demands of their age by adopting and reveling in performative, entrepreneurial roles that often involved them getting in front of their work as its mediator, star and promoter at each and any given opportunity. The very different but distinctly entrepreneurial stances of these two ‘enfant terribles’ from America and Germany were also both a mimicking and an exploitation of the business strategies of what, in the booming, ‘free- enterprise’ climate of the period, was a newly emerging art world rapidly transforming and growing all around them.

Koons’s Louis XIV and Kippenberger’s Untitled are two works that directly reflect and address this deliberate confusing of the dividing line between artist and art-object as well as the inflated and inflationary nature of the 1980s art market. While Koons’ sculpture, for example, plays with the idea of the artist and king as a dictator of taste, Kippenberger’s painting depicts its creator, literally intertwined with his own work. Here, Kippenberger has painted himself in a condition of apparently degraded failure in front of what is in fact one of his most recent and most successful artworks to date – the ‘Peter’ sculpture known as ‘Worktimer ’. He appears to be trying to float or elevate the work in a balloon while standing in a pose that is a pathetic parody of Pablo Picasso. Picasso, the undisputed king of art in the 20th Century, had, as Kippenberger well knew, famously had himself photographed standing heroically and manfully in his underpants outside his new chateau in the South of France in the late 1950s. Kippenberger’s self-mocking, self-degrading parody of this posturing reflects an extraordinary mixture of emulation, homage, ambition, but also regicide on the artist’s part. A similar claim could also be made for Koons’s appropriating of a statue of Louis XIV and having it cast in, what he always claims, is the democratic, egalitarian, common-denominating material of mass-appeal: stainless steel. In a reversal of the legend of King Midas, here, the absolute pinnacle of elitist, dictatorial taste – the Sun King – is rendered, by Koons’s munificent touch, as now open and amenable to all classes. Inflation and deflation – two concepts that relate to both economics and to the ego – are therefore, very much the shared themes behind the apparent ‘luxury and degradation’ of both of these visually very different, but thematically very similar works of art.