A new exhibition at London’s ICA titled “Keep Your Timber Limber” explores how artists since the 1940s to the present day have used drawing to address ideas critical and current to their time, ranging from the politics of gender and sexuality to feminist issues, war, censorship and race. Stretching from fashion to erotica, the works can all be viewed as being in some way transgressive, employing traditional and commercial drawing techniques to challenge specific social, political or stylistic conventions.

Keep Your Timber Limber (Works on Paper) runs from 19 June – 8 September 2013. The exhibition brings together the work of eight artists: Judith Bernstein, Tom of Finland, George Grosz, Margaret Harrison, Mike Kuchar, Cary Kwok, Antonio Lopez and Marlene McCarty.

Curated by Sarah McCrory, the exhibition draws on the way artists turned to the commercial realms of comics, fashion and illustration to revitalise drawing within the visual arts – many of the works in Keep Your Timber Limber (Works on Paper) were originally produced for a commercial context. One common aspect of these varied practices is a high level of technical skill – these are artists who often confounded critics of their subject matter unable to condemn their technique.

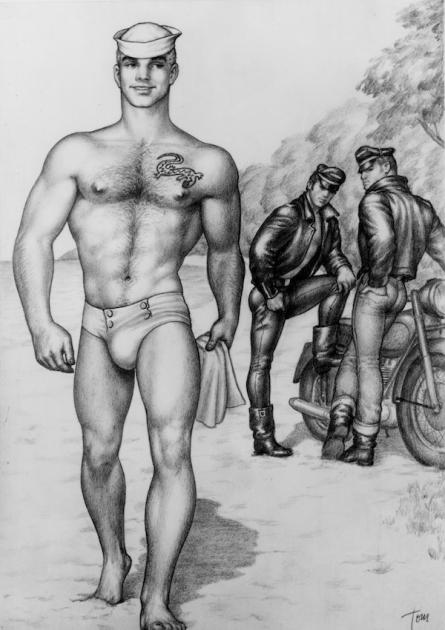

Choosing to step outside the boundaries of social acceptability, the works in Keep Your Timber Limber (Works on Paper) comprise modest proposals and trenchant political gestures. At first glance, Tom of Finland’s erotic drawings from the 1950s and 60s seem to be simply pornographic, though they always endeavor – as part of a personal manifesto – to present the healthy sex lives of gay men. Unusual at the time, homosexual erotica often portrayed men as aggressive, angry or shameful. Tom of Finland’s beaming protagonists illustrate these unions as joyful ones. Tom of Finland’s drawings have since become an important beacon for many homosexual men – found in physique pamphlets they were their first introduction to a world of which they were a part.

For 50 years, Judith Bernstein has been producing works that examine the power of men, particularly in the context of war (both Vietnam and Iraq), directly associating war with male sexual power and violence. Her giant screw drawings from the early 1970s are huge in scale, spreading across gallery walls. Often scrawling her own name defiantly into the gallery, Bernstein’s marking of her territory assumes a masculine gesture – a literal transferal of aggression and energy directly on to the wall. Bernstein’s works are angry and dominating, adopting a macho pose to critique a macho environment.

Also producing work in the early ‘70s, Margaret Harrison’s ‘regendered’ superheroes and hyper-sexualised women incorporate the language of cartoons and advertising, another male-dominated world. Emerging from a very British feminist sensibility, Harrison was influenced by the male-dominated 50s Pop Art movement. She revised comic book heroes such as Captain America, who she equipped with debilitating stilettos, and gave Playboy publisher Hugh Hefner a restrictive corset. Harrison humorously but poignantly draws pin-ups with food, manifesting the rhetoric of advertising and showing the lingerie-clad women as both juicy and delicious.

Mike Kuchar is predominately known for his underground film works alongside his twin brother George, influencing filmmakers such as John Waters and Jack Smith. Influenced by the New York and San Francisco gay underground scene and American comic culture, Kuchar produced, over several decades, extreme illustrated creations for homoerotic comics. The treatment offered to these well-built, well-endowed musclemen mirrors the treatment R. Crumb gave to his sturdy Gurls.

Cary Kwok’s exquisite ballpoint works depicting men ejaculating are at first hand both funny and unsettling. Using ballpoint pen, a medium associated with schoolchildren’s fan drawings of pop stars, he portrays a number of men with a visible and obvious set of beliefs or ethnic origin at a moment of climax. Although these men are stereotyped by clothing or race, their moment of ejaculation unites them in a physiological experience. During this moment of vulnerability each character lives outside of himself – his traits, beliefs and origin.

Emerging from a past as a member of AIDS activism collective Gran Fury, Marlene McCarty’s large scale ballpoint drawings come from two distinct series. The first, produced in the mid to late 90s portrays a series of girls well known for being murderers. Often notorious for having killed their parents, the girls are revealed through their clothes, as if viewed with X-ray glasses on – as if through their acts they have nothing left to hide. Their burgeoning sexuality and the nature of their crimes belie each other, but McCarty allows them to retain a sense of innocence whilst their see-through clothing surrenders them to the viewer. The second series revolves around relationships humans have had with primates, where a scientific or animal husbandry relationship has developed into a personal one. Still examining issues of dominance and domestic relationships, the sexual ambiguity of the scenarios is an abstract extension of her interest in gender and identity politics.

Coming from a more commercial approach to illustrative drawing, Antonio Lopez was a master at his craft. Situated within the 80s New York downtown scene, Lopez, at the time, was a celebrity and known for making the careers of social figures like Jessica Lange and Jerry Hall through not only his exquisite work, but through his associations within the upper echelons of the fashion world. These works show the scope of his work at the time, from illustrations of the scene he occupied through to the influence he had on Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent, his pioneering use of women of colour in illustration, including the representation of important queer icons, such as Josephine Baker and Grace Jones.

The single work from George Grosz is a homage to the career of an artist whose early work was used to highlight the injustices of the German wartime propaganda campaign. Many of the artists in Keep Your Timber Limber (Works on Paper) have had exhibitions closed down, or work stolen in protest, but Grosz was taken to court and regularly fined, and ultimately his work necessitated his fleeing from Nazi Germany. Grosz employed humour in his drawing, allowing a populist and accessible reading of often dark, satirical works criticizing figures of big business and wartime power – he considered himself a propagandist of the social revolution.

Keep Your Timber Limber ICA London 19 June 8 September

Image: Tom of Finland c 1960