Albrecht Dürer’s grandfather hailed from the Hungarian village of Ajtos. Dürer’s father migrated from Hungary to Germany, eventually settling in Nuremberg. Dürer, himself, lived in Nuremberg throughout his life but made several significant European journeys; along the river Rhine, twice crossing the Alps to Italy and, in later life, to the Low Countries.

Dürer embraced the ideals of the Renaissance while continuing to celebrate his German heritage

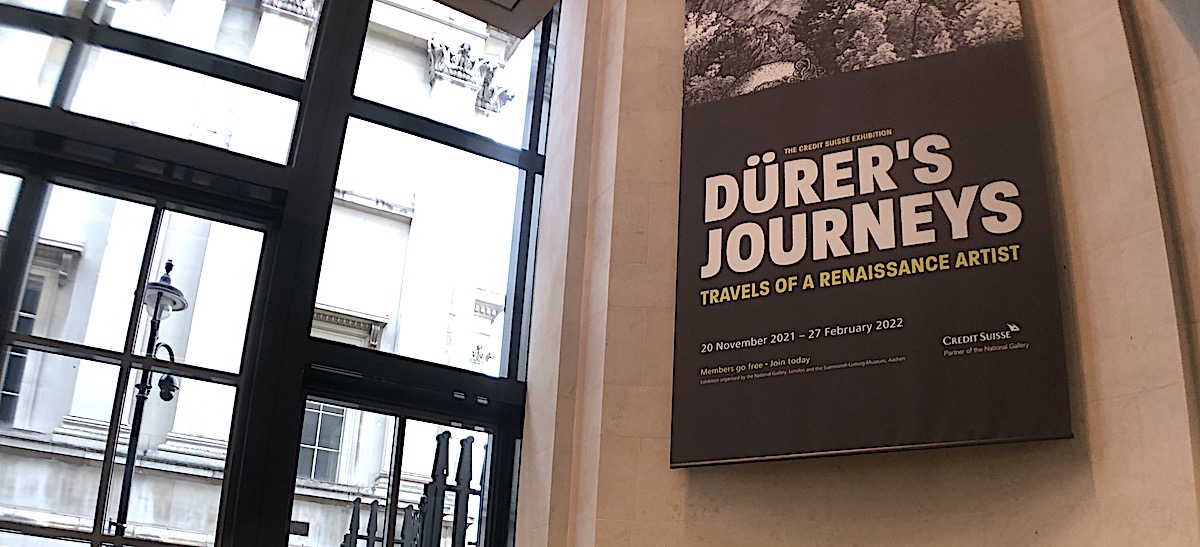

Journeys, therefore, shaped Dürer’s family significantly while also fuelling his curiosity and creativity, in part by bringing him into contact with a broader range of other artists and, over time, increasing his fame and influence. This is the first exhibition to focus on the artist through his travels, bringing us, as visitors and viewers, closer to the man himself and the people and places he visited. The world he inhabited and through which he travelled was one at the beginning of significant change, so by following his journeys, our eyes are opened to significant cultural shifts.

Dr Bonnie J. Noble has noted that: ‘After his trips to Venice and his encounter with the Italian Renaissance, Dürer embraced the ideals of the Renaissance that he experienced first-hand while continuing to celebrate his German heritage. Dürer was to master painting and surpass all others in printmaking, both relief and intaglio. Ultimately, he would rely on his prints for profit and recognition. Dürer not only experienced the transformation from Gothic to Renaissance, but he was also an agent of that change.’ The exhibition seeks to show us the influences Dürer absorbed on these journeys, as well as his influence on his culture and other artists as he developed his craft and became one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance.

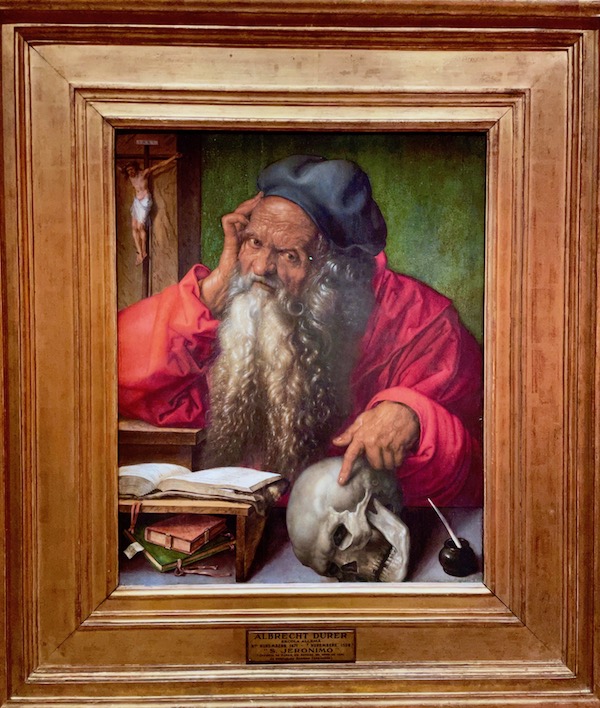

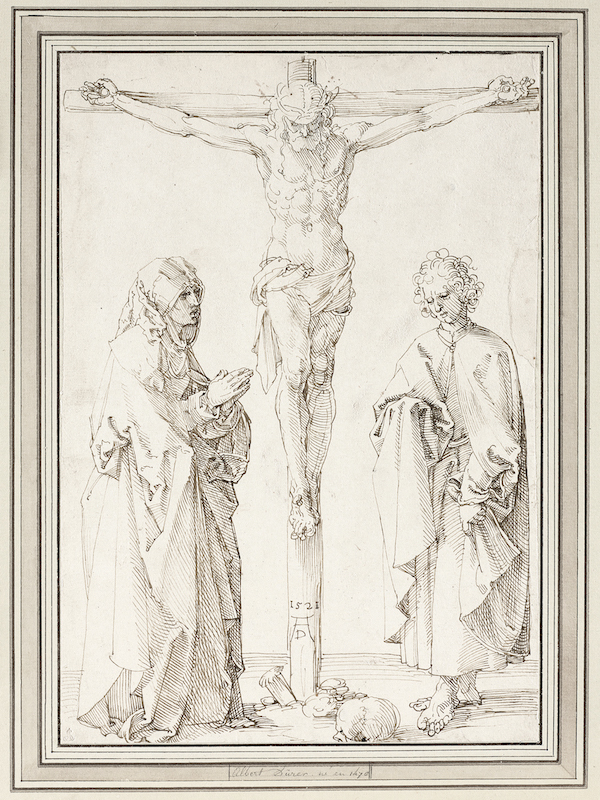

In the first room of the exhibition, we see how Dürer’s career progressed in the years following his return to Nuremberg after travelling to the Alps and Italy in the mid-1490s. The second room includes some of his early studies of human proportion made during his visit to Venice from 1505 to 1507. Room three has many of his best-known engravings and sees him return to Nuremberg, where he was employed by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, before embarking on a journey north to Aachen, where the coronation of the new Emperor Charles V was to take place. Portraits are featured in the fourth room of the exhibition, while Dürer’s observations as he sketched people, animals and townscapes are explored in the fifth. These include sheets from his silverpoint sketchbook with his most vivid and sensitive drawings. The artists Dürer met on his travels in the Low Countries are the theme of room six. The final room is devoted to the period in Antwerp, where Dürer became friendly with the Portuguese merchants’ agent Rodrigo de Almada. During and just after his journey to the Low Countries, Dürer experimented with new approaches to his representation of religious imagery due to his interest in Martin Luther’s insistence on the essentials of the Christian faith.

Through his journeys, we see Dürer develop from the apprentice who travelled to see work by Martin Schongauer and befriended the ageing Giovanni Bellini to the artist who became an influence on the work of Jan Gossaert, Conrad Meit, Quinten Massys, Lucas van Leyden, Joachim Patinir, and Joos van Cleve, among others. As he travelled, he became an innovator with, for example, the watercolour sketches made as he crossed over the Alps. These were the first pure landscapes ever produced in Western Art. Later, with Christ among the Doctors, he creatively fused the techniques of the Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance in one unique image. Additionally, Joseph Koerner believed that all ‘the great German artists derived their whole conception of what it means to be an artist from Durer’ who was the first artist in Germany ‘to theorize and codify an ideal of the beautiful as the aim of art.’

Dürer also became an entrepreneur, essentially eschewing painting for a time to tap into the possibilities opened by the invention of printing. Increasingly, he became able to fund his travels and increase his fame through prints and commissions. Instead of making engravings to order as had been the tradition to that point, he kept stocks of his work, selling many of these both at home and on his travels. Noble notes that: ‘Pictures made in multiples, such as the Adam and Eve engraving, meant that the ideas and designs of a German artist could be known in other regions and countries by large numbers of people. German artists could learn about classical art without travelling to Italy. More people could afford more pictures because prints are easier to produce and typically less expensive than paintings. The traditional, direct contract between artist and patron, where one object was hand-produced for one patron and one place, gave way to a situation where multiple images could be seen by unknown viewers under an infinite variety of circumstances.’

During his time in the Low Countries, Dürer drew the portrait of the great humanist Erasmus and began experimenting with new approaches to the Crucifixion story, perhaps with prints in mind. He was wrestling ‘with universal issues concerning the meaning and conduct of earthly life, following Martin Luther’s challenges to conventional religious belief’. His representation of religious imagery was influenced strongly by his interest in Luther’s beliefs. He viewed Luther as being ‘a truly honest man of God’, found personal solace in his writings, and owned a copy of every published work by him.

In 1520, when he thought Luther would be captured and killed by the church, Dürer contacted both the Court Secretary George Spalatin and Erasmus for help. He urged Erasmus to prove himself to be in the likeness of Christ by coming to the defence of Luther. Steven Ozment has explained how Dürer’s letter to Spalatin, by lamenting ‘the absence of a public image of Luther that justly acknowledged his life and work,’ led Spalatin to bring Lucas Cranach and Luther together to combine ‘their talents in support of their overlapping causes’, including the creation of that public image of Luther. Dürer later completed the circle with an image made in 1526 of Erasmus, which was to be his last engraving.

All this innovation was made possible for Dürer by the art he saw, the artists he met and the opportunities to expand his network of influence that occurred on his journeys. This exhibition shows us what he saw, who he met, and the mutuality of influence that occurred. As we follow in his footsteps on his journeys, not only do we come to know his work better but also come to know Dürer and his world more fully. They say that travel is an education. This exhibition proves that maxim to be true, both for Dürer and for we who visit and view.

Words Revd Jonathan Evens Photos © Artlyst 2021

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Dürer’s Journeys – Travels of a Renaissance Artist, National Gallery, 20 November 2021 – 27 February 2022