Andy Warhol (1928-1987) has, even since his death more than thirty years ago, retained a central position in the world of contemporary art. As the Directors’ Foreword to the catalogue of this new Tate Modern exhibition (shared with the Museum Ludwig in Cologne) points out, Warhol had multiple identities: “Depending on where we look, we find Warhol the commercial artist, Pop artist, or filmmaker; Warhol the business executive, celebrity, or sell out.” It just depends both or where we look, and also on how we choose to look.

An attempt is made to portray Warhol as the opponent and satirist of the kind of Minimal Abstraction – ELS

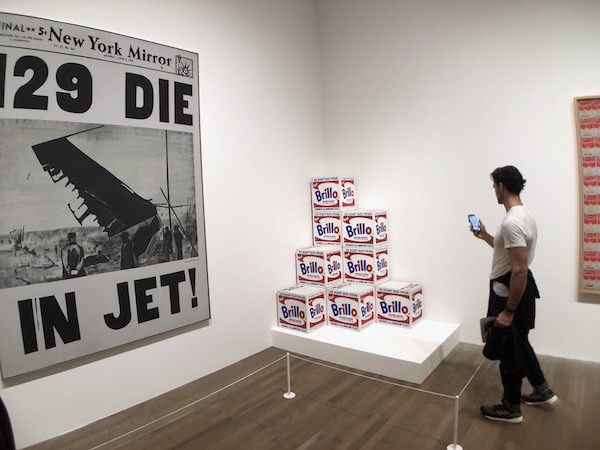

The new exhibition aims to offer the visitor a fairly comprehensive view of Warhol’s life, and of what he did. Doing so, it includes things that are both familiar and unfamiliar. It begins, for example, with a series of elegant line drawings, portraits of handsome young men, before it segues into the layouts he made as a successful commercial artist, specialising particularly in elegant ads for women’s shoes. Early on we get the paintings featuring serried ranks of Campbell’s Soup cans and of Cocoa-Cola bottles. Then a large painting with heads of Marilyn Monroe – an identical image, also arranged in rows, but with the colour fading away as the image moves from left to right, as if to remind the viewer that the celebrated subject is now dead and fading from our consciousness. Death plays quite a prominent role in these earlier works. There’s a woman jumping to her death from a high-rise building, a fatal car crash, the picture of an electric chair. And there are images of Jackie Kennedy, seen just before and immediately after her husband’s assassination.

Then we get Andy as a celebrity-obsessed New York scene-maker at the Factory, a place where ‘anything goes’, and also Andy as the victim in his turn of an assassination attempt. There’s a blow-up of the front-page of the New York Daily Sketch. It features a picture of his would-be assassin, Valerie Solanas, and carries the headline: “Actress Shoots Andy Warhol – Cries ‘He Controlled My Life’”.

An attempt is made to portray Warhol as the opponent and satirist of the kind of Minimal Abstraction that had now begun to challenge the reign of Pop in the New York art world.

The Tate exhibition offers a space full of free-floating, helium-filled pillows that you have to nudge your way through. The suggestion they offer is that these then newly fashionable minimal forms made by others were ephemeral nonsense, which would soon enough be ‘gone with the wind’.

Plus, there is a group of previously unseen, or at any rate little-seen, portraits of drag queens and transgender women, many of them black, as if to assure us that Andy, in the mid-1970s, when these were made, was already fully in step with today’s views about both gender and race.

Then, at the very end of the show, you get some ambiguous signals. First one of his portraits of Mao coloured to look like a girl. Second two likenesses of Lenin, glaring out full-face. The Lenin portraits, the catalogue seems to suggest, were originally scheduled for exhibition in America only. Was Andy getting ready to abandon capitalism for its enemy? I think not. These paintings belong to the same epoch as a large image of the head of the Statue of Liberty, a primary icon of American culture.

Even more ambiguous is the final exhibit – a huge canvas with repeated images in black-and-white of Leonardo’s painting of the Last Supper in Milan. The images come from a 19th-century photograph of the work, not from anything made more recently when efforts have been made to remove both accumulated grime and the effects of previous restorations. If you want a series of likenesses of an artistic corpse, here you have them. This, in spite of the fact that Warhol, under the influence of his Slovakian mother, seems to have been a Christian believer throughout his life.

For all his continuing renown, his work increasingly seems to embody the feelings of negativity we often have about contemporary art and what had become of it since its last days of real glory in the 1960s, when Pop was king. One reaction in today’s art world has been a rush towards conscious virtue and good works. Warhol certainly doesn’t embody anything resembling that. You look at his later work and think, quite simply: “Is that all?”