Looking back on her work, Hepworth identified three important sculptural forms to which she continually returned. These were the ‘standing form’, the ‘two forms’ and the ‘closed form’ which she associated with specific physical and emotional experiences, such as a figure standing at the top of a hill, or a mother holding a child:

‘The forms which have had special meaning for me since childhood have been the standing form (which is the translation of my feeling towards the human being standing in landscape); the two forms (which is the tender relationship of one living thing beside another); and the closed form, such as the oval, spherical or pierced form (sometimes incorporating colour) which translates for me the association of meaning of gesture in landscape; in the repose of say a mother & child, or the feeling of the embrace of living things, either in nature or in the human spirit.’

Reality exists only within ideas – Barbara Hepworth

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life begins with examples of these forms and the exhibition demonstrates that much of Hepworth’s art and life attempted the synthesis of material and idea, the singular and the universal, that is implicit in this quote. The exhibition also explores how Hepworth’s wide sphere of interests comprising music, dance, science, space exploration, politics and religion, as well as events in her personal life, influenced her work. As the Hepworth Wakefield’s curator Eleanor Clayton notes: ‘Deeply spiritual and passionately engaged with political, social and technological debates in the 20th century, Hepworth was obsessed with how the physical encounter with sculpture could impact the viewer and alter their perception of the world.’

For Hepworth, both Anglicanism and Christian Science, at differing points in time, were of significant spiritual importance to her. However, it was Christian Science, a religion based on an alternative reading of the Bible, that had the more obvious impact on her work itself. Her first piercing of a closed form occurred in 1931 and it is probable that a spiritual aspect was involved, given the commitment that she, together with Ben and Winifred Nicholson, had at this time to Christian Science. Later, in 1937, she suggested, in language taken from the teachings of Christian Science, that it is ‘a piercing of the superficial surfaces of material existence that gives a work of art its own life and purpose and significant power.’

When, in 1933, she became a member of Abstraction-Création, the Paris-based group dedicated to non-representational art, she wrote in their journal that ‘reality exists only within ideas’. Again, this, too, relates to Christian Science whose central text distinguishes between the ‘mortal mind’, which perceives the physical world, and the ‘divine Mind’, which represents the true, intangible nature of existence.

Hepworth also embraced scientific advances by combining these with her sense of spirituality, writing in 1966: ‘I regard the present era of flight and projection into space as a tremendous expansion of our sensibilities, and space sculpture and kinetic forms are an expression of it; but in order to appreciate this fully I think that we must affirm some ancient stability.’ Genesis III (1966) sees celestial, circular forms floating amid a cosmic background of spattered ink. Its biblical title suggests a connection between forms that Hepworth related to space exploration and her continued Christian faith.

The last two decades of her life were a time in which she renewed her connections with Anglicanism and in which the crucifixion featured as a source of inspiration. In an interview given in 1964, she spoke of a wish to “do an abstract crucifixion”. Then, in 1965 and 1966, she created the paintings Construction I and II, the armature of drawn lines from which was translated into her 1966-67 sculpture Construction (Crucifixion). A cast of this sculpture was controversially installed at Salisbury Cathedral by Hepworth’s friend and student, the Revd Professor Moelwyn Merchant.

Three verticals are linked by a single horizontal bar, and by two other horizontals at different heights. A large circle, attached to the intersection of the horizontal and vertical lines, is painted citrus yellow on one side and blue on the other. At the bottom of the central vertical is red on its own beneath the blue side of the circle, and red and white beneath the yellow. On the yellow side, a metal hoop encircles the point of crossing.

While the colours and grid structure are a homage to Piet Mondrian, the shapes draw once again on Christian Science. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, wrote: ‘The real Life, or Mind, and its opposite, the so-called material life and mind, are figured by two geometrical symbols, a circle or sphere and a straight line. The circle represents the infinite without beginning or end; the straight line represents the finite, which has both beginning and end.’

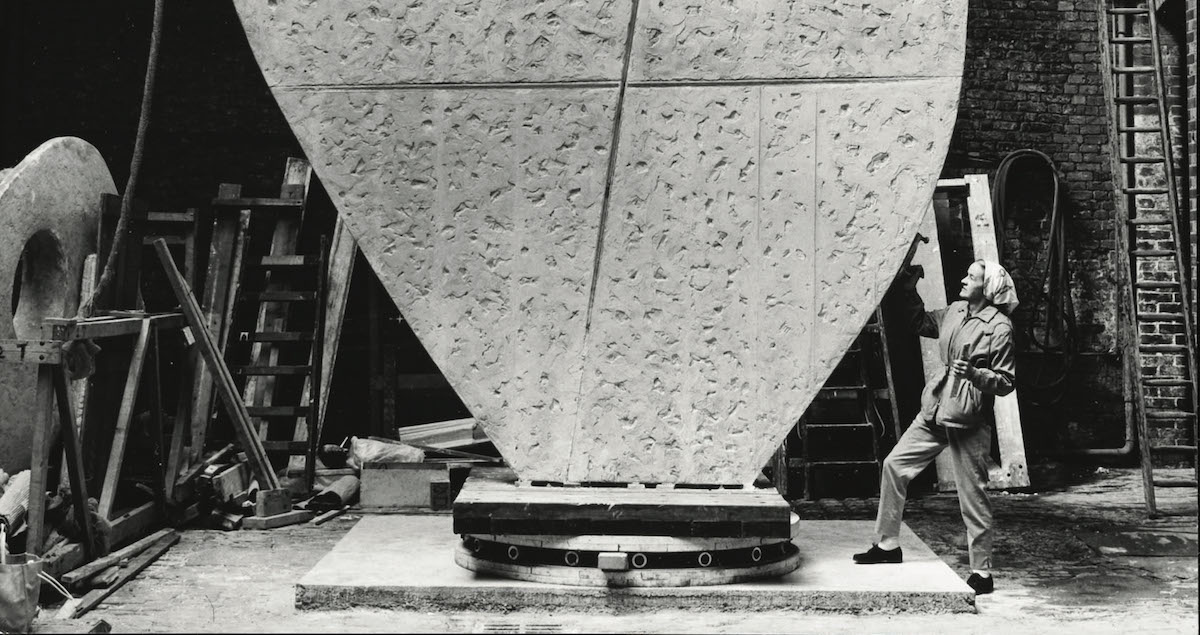

A cross, in the form of one vertical line crossed by two horizontals, combined with a circle is also to be found on the immense Single Form created for the United Nations as a memorial to Dag Hammarskjöld and made to the glory of God.

Semi-circles, circles, and holes abound in this period in works with both sun and moon serving as inspiration. Her repeated use of circles or spheres, while relating to space exploration, also reflect her faith in Christian Science. Its central text states that the ‘divine Mind’ – the spiritual entity of which all existence is a part – ‘is in perpetual motion. Its symbol is the sphere.’

The works in this exhibition demonstrate Hepworth’s intuitive and spiritual understandings of form and energy. Form is inherent in the material and needs to be discerned by the artist to be realised. Energy is found in ideas, the imaginative concept that gives life and vitality to the material; and this vitality is its spiritual inner life, force and energy. This is her synthesis of material and idea, the singular and the universal.

Hepworth described the task of the artist in religious terms, saying that an artistic sensibility revealed a ‘vision of a world that could be possible . . . inclusive of all vitality and serenity, harmony and dynamic movement.’ Artists passionately affirm and reaffirm and demonstrate in their plastic medium ‘faith that this world of ideas does exist.’ In an essay for The Christian Science Monitor in 1965, Hepworth concluded: ‘A sculpture should be an act of praise, an enduring expression of the divine spirit.’

Top Photo: Barbara Hepworth at work on the plaster for Single Form, January 1962, at the Morris Singer foundry. © Bowness, Photo: Morgan-Wells

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life, The Hepworth Wakefield, 21 May 2021 – 27 February 2022