Appropriately entitled ‘You Can’t Please All’, the show at Tate Modern for this celebrated Indian artist is first international respective of his work to be held anywhere since his death in 2003.

The handlist to the exhibition rashly asserts that Khakhar ‘played a central role in modern Indian art.’ This claim is difficult to sustain because one of the things that has delayed the recognition of contemporary work from India is precisely this – a lack of any kind of central focus, of any dominant tendency or school, any region in the vast extent of the subcontinent that plays a central role. The situation was and is very different in post Cultural Revolution China. In China there are just two major institutions that really count, the Central Academy in Beijing and the China Academy in Hangzhou, and most of the commercial action takes place in two locations – Shanghai and Hong Kong. Indian culture is not nearly so tidy, and the impact of contemporary Indian art has been correspondingly muted.

Ai Weiwei, recently the cause of so much excitement here in the West, has tended to distort western perceptions about the way things are structured in China. Celebrated as he has now become, he remains a somewhat marginal figure in his own country. This much at least he has in common with Khakhar, though the latter’s marginalization was of a somewhat different sort and arose from other causes, personal rather than political. This doesn’t, however, alter the fact that Khakhar is a very affecting artist, in many ways much more so than Ai Weiwei. He is the hero of a tragic story, one that, when understood, carries a powerful emotional charge.

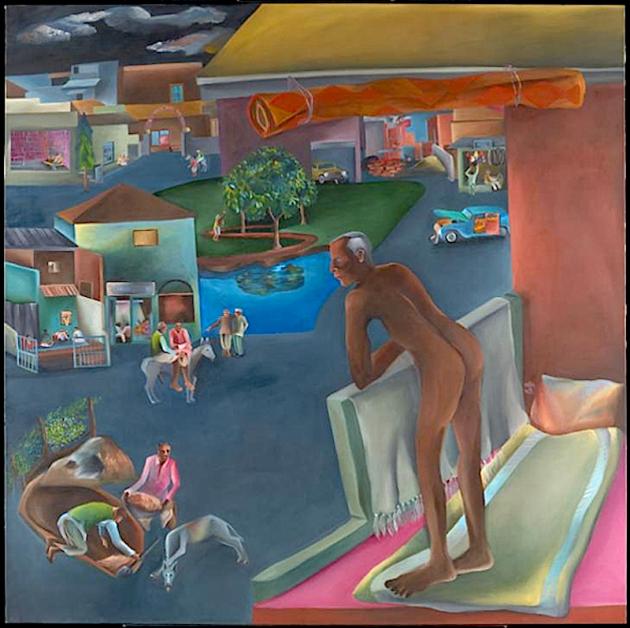

Born in Mumbai, Khakhar spent his career in Gujarat, which is hardly the centre of the cultural action in his country. As a painter, he was largely self-taught. One of his points of reference in European art was the work of a fellow autodidact, the Douanier Rousseau. He also reacted away from European Modernist fashions, towards the kind of narrative painting that had long existed in India, for example in the miniature paintings made for both Mughal and Hindu courts. He did not, however, embrace this tradition in its purest form. Its main impact on him was through the so-called Company School paintings made by Indian artists for European patrons living and working in India.

Where Khakhar is very recognisably ‘contemporary’ this is because of his solipsism. His most powerful paintings are all, in one way or another, narratives about himself. They are confessions made, with a slightly touching awkwardness, about two things: his own homosexuality, and his long struggle with mortal illness. A sign placed at the entrance to the galleries that hold the show warns visitors about ‘explicit sexual content’. In fact, these are some of the least erotic (though nevertheless extremely explicit) paintings about gay sex that it is possible to imagine. The acts of love portrayed tend to have a slightly shame-faced quality, a touching awkwardness. As the artist himself pointed out, shame about homosexual desire, and homosexual acts, was something imported into India by Europeans. It didn’t exist before they arrived.

The real shock comes from a series of paintings chronicling the progress and physical consequences of prostate cancer, diagnosed in 1998 – the disease that eventually killed him. In some of these, for example, one sees the artist being subjected to brutal enemas. Or else the cancer is personified as a swarm of little biting creatures. As the handlist primly points out: ‘There is a comic edge to these works, both in their titles and in Khakhar’s use of translucent glazes and bright colours,’

The truth is that Khakhar is an apparently ‘naïve’ artist who is not at all naïve. He is a brutally effective ironist.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photo: Courtesy Tate Modern © All rights reserved