In the midst of the chaos in the London art world caused by the current pandemic an artist occasionally shows up who seems serenely separated from the ongoing turmoil. This is the case with the new Mark Edwards exhibition just opened at the Catto Gallery in Hampstead. It consists of a series of paintings, all of the snow scenes, peopled with men in hats and formal overcoats. They stand with their backs turned to you, amid leafless trees, looking intently at something. What they are looking at is generally a house with unlit windows – nobody at home. Occasionally, instead, the object of their gaze at is a steam-age train on a viaduct.

There are a few additional props. Very often a red balloon – just one – hanging from a branch, floating, rolling on the snow-covered ground, floating in mid-air. Occasionally, an overcoat, also hanging from a branch. One painting has a dog, looking at the balloon, while its master looks elsewhere. Another has a bonfire, roaring beside the unoccupied house, a little too close for comfort. In yet another, the bonfire exists out of sight, turning the winter woodland red. Quite often, the presence of additional figures is suggested, their shadows cast upon the ground.

The catalogue essay tells one coyly that the painter ‘has no idea what the paintings are about’, though he welcomes the vivid explanations they evoke from some of his buyers. However, he suggests comparisons with the work of writers such as Pinter, Beckett and Brecht.

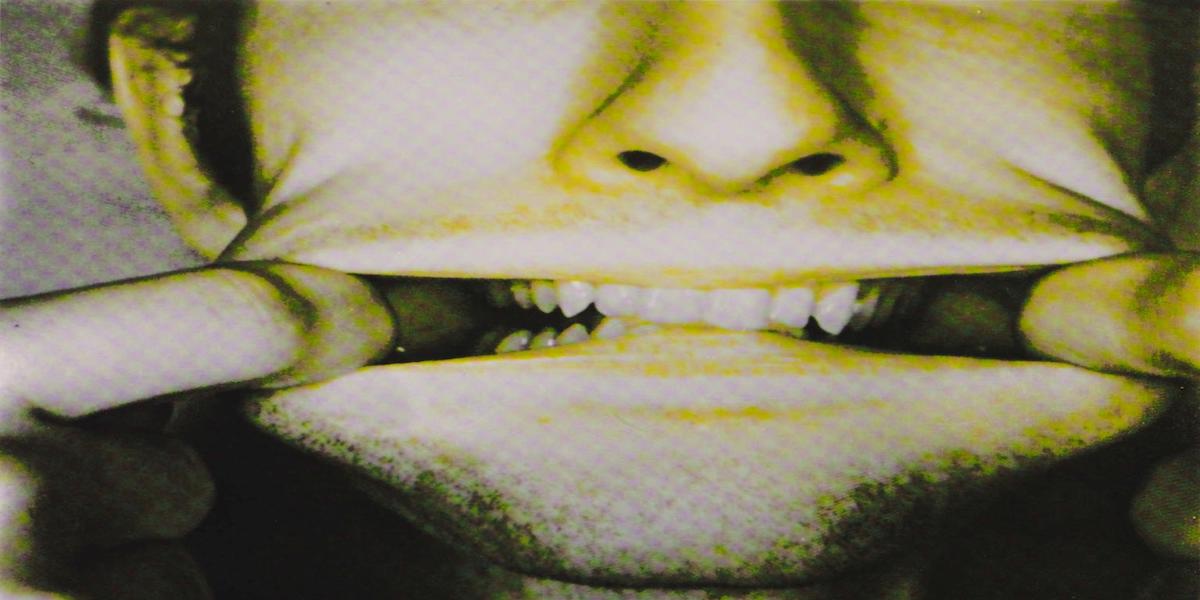

In fact, this series of works exemplifies the power of certain kinds of purely visual art to convey ambiguous messages. As opposed, for instance, to what you might find in the much bigger Bruce Nauman exhibition now at Tate Modern, where there are also works that depend on ambiguity for their effect. In their case, the ambiguity depends on the relentlessly repetitive use of words, spelled out in neon: ‘Sick and Lice/Sick and Die/Well and Live/Well and Die’. Nauman wants to hit you with a sledge-hammer. Edwards proposes something you might like to hang over your sofa.

Artists like Mark Edwards, who cater to a private clientele, selling them home-ready artworks at reasonable prices, are currently in much better situations than some of the big names, among them not only Bruce Nauman at Tate Modern but also Damien Hirst, who has recently opened a big show solo show of his own work at his gallery in Newport Street London, and David Hockney, now resident in France.

The Hirst show, entitled End of A Century and running till Match 7th next year, received an enthusiastic review in The Guardian from their art-critic Jonathon Jones:

‘This [he said] is a hugely entertaining and memorable epic trip to the 1990s when Hirst captured the dark mood of a fin de siècle. His personal collection of his own work is big enough to make a museum, his obsession with death once again urgent.’

ArtNetNews, however, was less laudatory. It said:

‘With all the shameless self-branding, ostentatious installation, and market madness that has defined his late-career work, it’s easy to forget that Damien Hirst was once seen as a fresh, cutting edge “Young British Artist”.’

This trip to the art world as it was twenty-and-more years ago seems to have little to tell one about what is happening there now. It may be obsessively about death yet seems paradoxically irrelevant in the midst of the CoVid plague.

David Hockney is now resident in France and is due to open a solo show at the RA in London on March 27 next year. Entitled The Arrival of Spring, Normandy 2020, this will feature 116 new works, ‘painted’ on an iPad and then printed on paper.

The announcement on the web tells one that: ‘Made in the spring of 2020, during a period of intense activity at his home in Normandy, this exhibition charts the unfolding of spring, from beginning to end, and is a joyous celebration of the seasons.’

Creating it also, as it happens, spanned the early phase of the pandemic, though you wouldn’t guess that from looking at the images accompanying the announcement.

These suggest that the main influence for the show is likely to have been none other than long-ago Monet. They look like slightly naïve versions of some of Monet’s most typical landscapes, though without the occasionally intrusive factory smokestacks. Technologically innovative they may be. Visually innovative they aren’t.

What these three events by big-name artists seem to tell one is that they are all, in their different ways, treading water, waiting for the art world that made them celebrated to return. That is, if it ever does so. Edwards, catering to a faithful over-the-sofa clientele, seems to be in a much better position. He is also, as it happens, producing work that seems to resonate with our present situation, whether or not he intended to do so. The visual metaphors are there.

Top Photo: Bruce Nauman ‘e’ 1970 Courtesy Tate