Most great artistic movements begin as a reaction to the art and times that precede them. Impressionism in the 19th century. Surrealism, Dadaism and the YBAs in the 20th c. Baroque began in Rome around 1600 in response to the austere 17th-century Protestant culture of the Netherlands.

The Baroque art of Rome was the cinema of its times – SH

Two figures stand out. The painter Michelangelo Mersi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) and the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). In the 1600s, Caravaggio’s powerful paintings, full of theatrical lighting, caused a sensation with their sensual naturalism. There would be many followers, including the father and daughter duo the Gentileschi’s, Borgianni, Barolomeo and Baglione, to name but a few. It was just a few years after the death of Caravaggio in 1610 that the virtuoso sculptor Bernini burst onto the scene, giving new impetus to Caravaggio’s legacy with his intense bravura sculptures.

In just a few years, Rome was transformed into a vibrant creative hub. Although the ‘movement’ was not named Baroque until much later – from the Portuguese Barocco, an irregular natural pearl – the radical artistic climate of the Counter-Reformation acted as a stimulant that gave birth to a dialogue between sculptors and painters. Emergent religious orders, including the Jesuits and the Orations, busily commissioned new artworks. Landscape painting became increasingly popular, as did the rise in the playful, fantastic and the grotesque. Caravaggio’s influence was enormous. Particularly his works on public display that included the Martyrdom of St. Matthew in the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi, and The Conversion of Saul, with its dynamically lit horse, from the Cerasi Chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo. With their bravura chiaroscuro, dramatic illusionism and story-telling, they created an immediate furore.

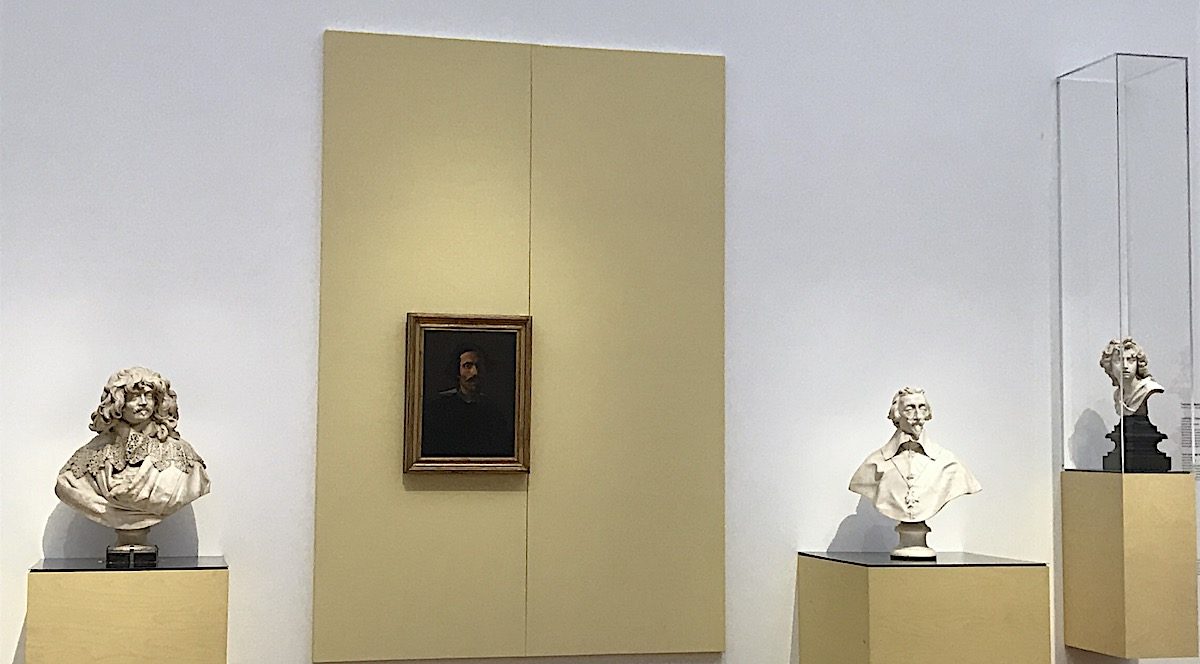

The exhibition Caravaggio-Bernini, Baroque in Rome at the Rijksmuseum, curated by the Senior Curator of Sculpture Frits Scholten, is now showing more than 70 masterpieces by Caravaggio, Bernini and their contemporaries, on loan from international museums and private collections. The understated hang, with its spare use of fabric panels and subtle colour, gives a quiet backdrop to the drama of the Baroque imagery. Entering the gallery, the viewer is confronted – one may say – transfixed – by Bernini’s sensational Medusa with its halo of writhing snakes, on loan from Rome’s Musei Capitolini. The technical virtuosity has clearly been devised to evoke stupefaction (stupore) in the stunned viewer. In the same gallery is Caravaggio’s depiction of Narcissus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses – the story of a handsome self-obsessed youth, eternally condemned to the pain of unrequited love, when he becomes besotted by his own reflection. This subject falls into the category of the ‘profane’, the Neoplatonic approach popular in the early modern era that referred to pagan culture. It might also be argued that the painting illustrates the growing (modern) sense of psychological self-reflection beginning to stir in this period.

The exhibition has been organised around a number of the critical artistic concepts of the time. These include wonderment (meraviglia), vivacity (vivezza), motion (mota) jest (scherzo) and horror (terribilità). In the early Modern Age, wonderment – la merviglia and the associated astonishment (stupore) became key poetic concepts. This was the precursor to the wonderment described by British Romantic poets such as Wordsworth for whom nature was awe-inspiring, and the later poetry of the Rilke and Yeats. These expressions of terror and sublime awe in the fine arts were often rendered as dynamic surprise and wonderment (admirato). Such emotions are closely bound up with divine visions, suggested in Louis Finson’s Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy, after Caravaggio, and Bernini’s St. Teresa, which to modern eyes look pretty similar to sexual elation.

‘Love’ was a bit of a problem in the early modern era. Female virtue was seen by the church as reflecting the chastity of Mary, the Mother of God. While sexuality, within the church’s teachings at least, was confined to procreation. Carnal lust is seen as bestial and belonging to the animals. Young men were advised to satisfy their sexual urges before marriage in order to achieve temperance later. Women, of course, suffered from these double standards with the development of the template of the Madonna and Whore. Despite the plethora of androgynous saints and titillating ivory-skinned young men, actual Sodomy (as same sex-relationships tended to be called) was theoretically punishable by death.

The section Orrore and Terribilità in the exhibition is dominated by biblical stories. The beheading of Goliath or Holofernes – their faces distorted with pain – that deliberately and unsparingly engage the viewer in the horrors they are witnessing. Within the vocabulary of the Baroque aesthetic – the motions of fear and terror, as portrayed by Caravaggio and Orazio Gentileschi – carry a positive impact that denotes the power and success of a particular artwork. To the modern eye, many of these paintings seem filmic with their dramatic agitated scenes of violence.

The Baroque art of Rome was the cinema of its times. Affect and action, the intensity of expression, were suggested by vibrant movement. This was accompanied by a gaze directed out beyond the picture space (as if from a movie screen) towards the audience/viewer, highlighted by the effects of chiaroscuro. Above all, Roman Baroque was an art of emotion. Internal feelings were heightened so that they could be equally experienced by the viewer. Lips quiver, mouths scream in distress and ecstasy, tears flow, hair streams and muscles clench. The shocking, the wonderful and the gruesome are melded together to form what W.B. Yeats would later call a ‘terrible beauty’.

Words/Top Photo And Inset Photo 1 Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2020

Caravaggio-Bernini. Baroque in Rome, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 14 February – 7 June 2020

Sue Hubbard’s latest novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth. Her fourth poetry collection Swimming to Albania is due from Salmon Press this spring.