At the moment Tate Modern offers retrospective exhibitions of three very different artists – Bonnard (French), Franz West (Austrian) and Dorothea Tanning (American). They have just one thing in common: all of them are dead. It is as if Tate is terrified to offer this honour to anyone living. Why? Perhaps the fear is that a living artist might somehow surprise them, by deviating from the path of official approval so carefully prepared.

Perhaps the fear is that a living artist might somehow surprise by deviating from the path of official approval so carefully prepared – ELS

Though Bonnard is the best known of the three, Tanning is in some ways the most interesting. The show devoted to her work is part of the great push now going on, to offer more recognition to female artists – to make a larger and more secure place for them in the firmament of what we still call Modern Art, even though most of it belongs not to the artistic here-and-now, but to the day-before-yesterday. Tanning lived to a great age. When she died in 2012, she was 101. She was the last companion of the leading Surrealist Max Ernst. In historical terms, she belonged to a very belated tag-end of the International Surrealist Movement.

As the comprehensive show at Tate Modern demonstrates, she began pretty much in the world of slick 1930s fashion illustration and turned herself into something entirely different. Her best-known painting Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, made in 1943, belongs to a relatively early phase of her work. It shows two figures, young girls in ragged costumes, who seem to be in danger of being attacked by a gigantic sunflower, which has crawled towards them up a flight of steps. The theatrical nature of the pictorial space reminds one that, at this time of her career she made designs for the ballet, working for example with Balanchine.

I find her later, more painterly work more interesting. Here the figures seem to melt into one another, and into the background of the composition. The effect is repeated in three dimensions, in sculptures made of soft materials – bodies, so it seems, struggling to define themselves fully. This tendency fulfills itself in a room-sized installation called Chambre 207, Hôtel du Pavot, made in 1970-3. In this, the bodies seem to burst out of the walls.

This installation, faintly sinister, is betwixt-and-between. It isn’t quite late-phase Marcel Duchamp, and it isn’t Pop Art. Like quite many female artists who enrolled in on or other of the great 20th-century art movements, Tanning never quite belonged. Yet, particularly in her later work, she has an instantly recognisable, slightly creepy individuality.

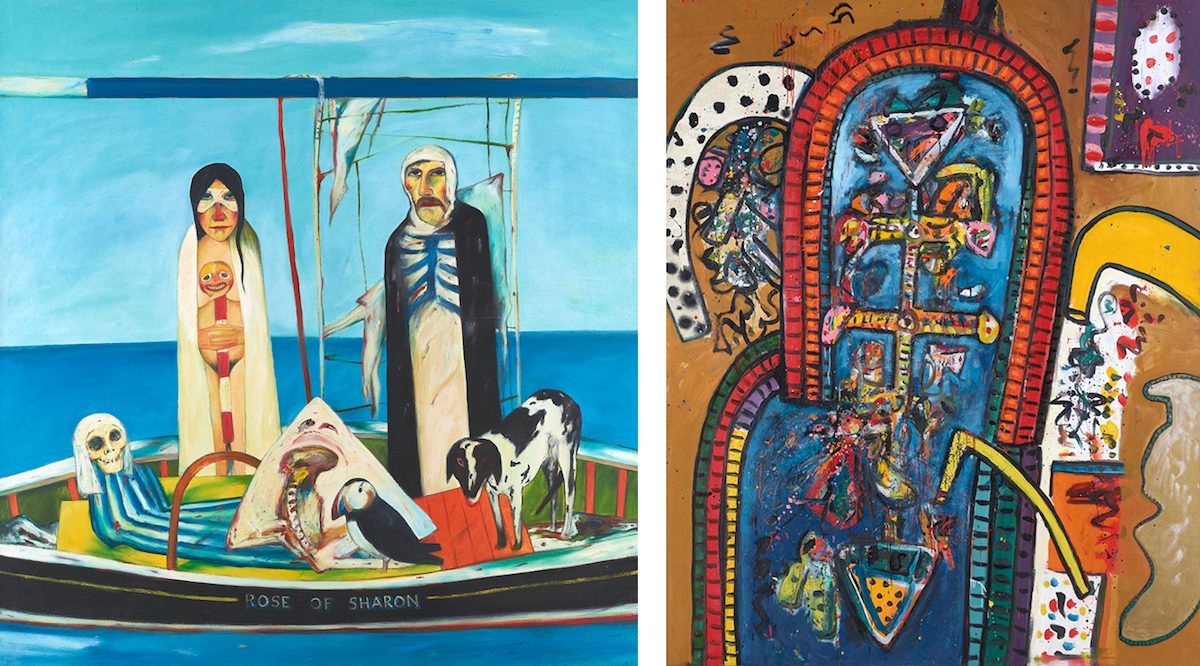

At Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, which generally, much to its owner’s credit, showcases the living, there are two dead artists. The show is called Cradle of Magic and features two Scottish artists, Alan Davie and John Bellany. Davie, like Tanning, lived to a great age. He was born in 1920 and died in 2014. Bellany (1948-2013) had a briefer and, towards the end, a more troubled career.

The paintings are shown in a slightly higgeldy-piggeldy way. In some rooms of the gallery one artist reigns alone. In other rooms, they are jammed together. Davie fits more easily into the story of late 20th, early 21st-century art, but for me, Bellany is the more interesting artist. As

As the gallery notes tell one: “Davie worked rapidly on the studio floor using homemade paints to produce vibrantly coloured shapes, signs and biomorphic forms. He wrote that the spontaneous exploration of the magical possibilities of colour was ‘perhaps the most important element in my painting (and indeed my life).’”

Though he was influenced by ‘free jazz’, his work now gives the impression of being shut in. It’s busy and energetic but opens no doors.

Bellany is not like that. Born in the small fishing town of Port Seton, he struggled with depression and alcoholism all his life. A visit to Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1967 exposed him to the worst that humanity could do. He also looked beyond the modern, to the masters of the past – Grünewald and Rembrandt for example. He looked to at the great archetypes of Western art – for example at images of the Crucifixion. His work, at least for me, is resonant, in a way that Davie isn’t.

He is not a painter of the absolute first rank – too costive, too convoluted – but you do remember his images once you have met them.

John Bellany (1942–2013) and Alan Davie (1920–2014) ‘Cradle of Magic’ Newport Street Gallery until 2 June Free

Various Tate Exhibitions Find Exhibitions Here