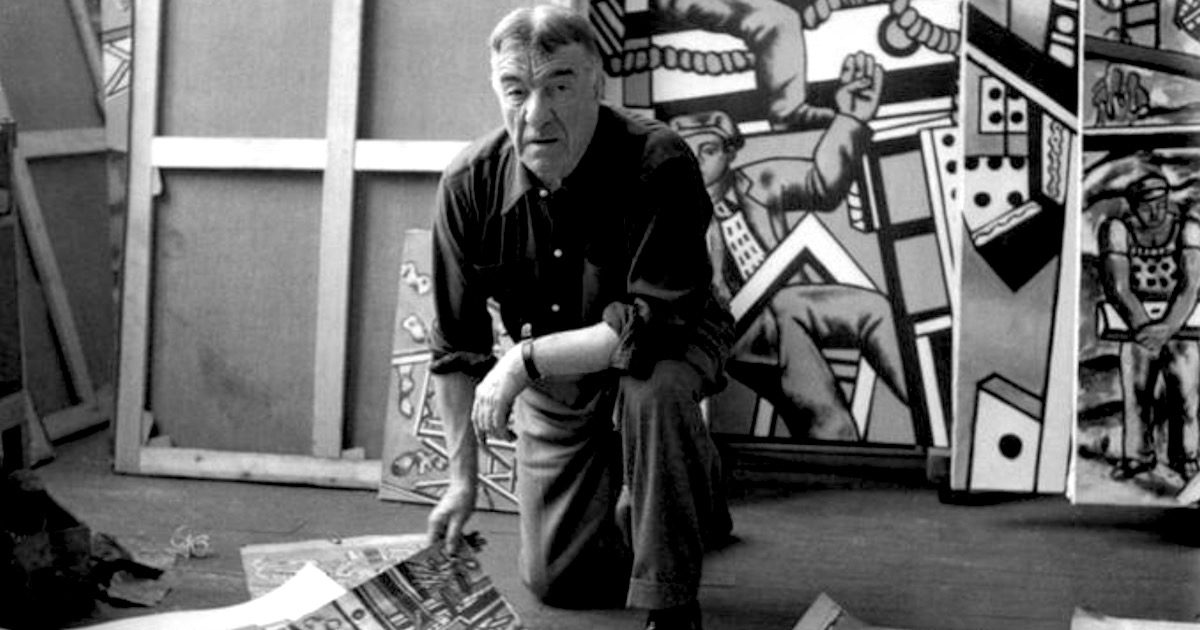

It was captivating to see the Fernand Léger exhibition (until 17 March 2019) at Tate Liverpool. This is a show celebrating one of the twentieth centuries most celebrated French artists. The exhibition leads us through a journey into our past, present and future and provides much to think about on many levels, including political, and creative collaborations that make us question our current and future society.

Like many of his successors such as Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol we also see Léger‘s fascination with advertising and popular culture – AL

Léger‘s inspiration and creation of film and art was during what was termed as the ‘mechanical age’. The exhibition draws attention to Léger‘s interest in his times, the experiences he had and his own social conscience emanates throughout his work. An artist who served in the First World War, it dawns on you how someone who suffered a severe mustard gas attack and almost died managed to somehow objectify these personal experiences from his art with such dignity and yet also conveying messages about his ideal society throughout. This is not an exhibition showing the horrors of war but instead, an exhibition that questions and embraces the movement of the machine within his art as well as embracing the movements in art surrounding him at the time and his utopian vision.

Léger makes reference to the utopian and dystopian aspects of society. For instance, in his collaboration with poet Blaise Cendrars, the two artists who were both wounded during the First World War come together to write and design a book called, The End of the World filmed by the Angel of N. -D., Published in 1919, ‘‘the book features an apocalyptic end of – the – world scenario.’’ This idea of worlds and endings and new beginnings, Utopian and Dystopian themes starts to weave throughout the exhibition.

This exhibition is also about reactions towards art and the role art plays in the past as well as our present society. It starts with Léger‘s interest in Cubism and how Paul Cezanne had a strong influence upon his work. Cezanne was deemed as the forerunner of modern art and Cubism, after breaking away from Impressionism with his famous fragmented paintings of ‘Mont Saint Victoire’. Léger‘s works begin as abstractions. You can see his interest in broken and fragmented forms inspired by Cezanne and later ‘Cubism’, a movement that celebrated the fractured elements of forms, bringing everything down to its pure essence, looking at the world as the sphere, cylinder, cone and the cube. Everything is simplified through these forms.

It is riveting to see how Léger began with abstraction and later in his career became more interested in the human figure. It occurred to me that it is more often, the other way round; figuration towards abstraction. The machine age is a prominent force in Ferdinand Léger ‘s early work. The exhibition highlights his interest in his own society, the changes taking place and the avant – guard the experimentation and combination of different art forms. The film he created, ‘Mechanical Ballet’ also emphasised this fragmentation and celebration of the city and the machine, the repetition and montage of life, the new quick pace, the speeding up of everything. One reflects on how much slower things must have been before the machine age and what a shock and also a sense of excitement there must have been with new technologies emerging. Previously, things were more often handmade, more peaceful. The human hand was the machine and the controller. It must have been an enormous thing to suddenly witness machines take over people.

The film, ‘Mechanical ballet’, I feel emphasises the experiences of people through this sudden change. There is this fascination with the metropolis and how engineering and technology and robots are suddenly the instigators within our society. Man is no longer the main controller of things. Léger must have heard the noise and seen this change, and this inspired him with his work.

Like many of his successors such as Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol we also see Léger‘s fascination with advertising and popular culture. and the celebration of forms of the machine as in ‘The wheel11, 1920.’ His interest in abstract planes and the human figure lined up against each other are an inspiration.

I was intrigued by the painting ‘’the disc, 1918’,’ the colours, it’s abstractions and sensuality. I realise this painting must have had a significant effect upon me many years ago. Somehow it has always been there in my subconscious. When you see this painting, it generates a mixture of thoughts and emotions. It has that feeling of pop art about it. It is a ‘target’, imagery that has become so popular it is now imprinted into our subconscious. There is this wonderful sense of design and pattern, a celebration of the mechanics he saw, of new technologies as in his work, ‘The propellers,1918.’ Advertising, the billboard and neon signs within the city inspired Léger to form his own visual language, celebrating the city and technology in all its raw and repetitive brutality.

I was struck by the way Léger enjoys this mechanical language, using the machine as the symbolic template for his compositions and visual studies. There is a crisp but also painterly approach in his work. Colour, drawing and shape come alive upon the canvas. He is not afraid to explore this world of form, colour and shape. He is enjoying it. He is also drawing and playing with ideas and themes through juxtaposition and self-referential approaches. In some of his paintings, I can see Matisse-like compositions overlayed with bold black line drawings, something that Matisse also did himself, which was to use this bold black line, inspired by the Japanese woodblock print. Léger draws our attention to this interconnection and repetition of visual language in art history.

Language and typography span outwards towards a visual and experimental poetry and visual language of words and forms. Just as Picasso was distorting and fragmenting, Léger was also devising his own style to convert these distortions and fragmentation’s. During this time there was a mutual interest in art and change, the sharing of ideas, of intellectualism, collaborations between poets and artists. They were all searching for something and discovering the inspiration and driving force in their work.

Léger is talented on so many levels. He is a painter, a designer, illustrator, artist and filmmaker. He embraced everything within his times and explored this within his art. Look at the books and zines. The book ‘Broom’, an international magazine of the arts. 1921 to 1924, Introduces European Avant – garde to America through images by Derain and Gris and Léger. These are inspiring books and zines and remind us in a nostalgic way of how much we miss their physical form. There was a time when they were read daily within libraries, cafes, studios, and were accessible to everyone. Many of the covers were designed by leading artists and poets of the time including Léger. These zines and books were artworks in their own right.

The First World War becomes the horror in which many of these artists and poets collaborated in order to make sense of the world around them. These illustrated books and journals are so beautiful and are fascinating. There is this element of emphasising the commercial world in the way Liechtenstein did later.

There is also, I feel, an element of suspicion. The films Leger collaborated on and made celebrate the new world order but also seem to look at it with mistrust.

There is this sense that people are becoming like machines themselves. People are becoming robots, inhuman. What omen has this new world order brought to the peaceful world? We could also equate this with our feelings about our present society.

And yet throughout his career, Léger remains optimistic. He is a socialist seeking a better world. His work, ‘Essential Happiness, New Pleasures, 1937/2011’, is a featured work within the exhibition, a work made in collaboration with architect and designer, Charlotte Perriand. This large-scale work first appeared at the International Exposition in Paris in 1937. The mural promoted rural life, ‘’urging nations to work collectively to forge a better future for all.’’ It is quite hard to believe that this modern montage piece reached so far back. 1937, marked ‘The Exposition des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne.’ The exhibition also highlighted the patriotism of different countries and opposing forces to be reckoned with such as that of the Nazis represented by Hitlers Eagle and Swastica, yet to destroy the world and the Soviet Pavilion was represented by Vera Mukhina’s giant monument, ‘Worker and Kolkhoz Woman’. The exhibition marked a huge turning point and change in what was to come.

As the Tate exhibition continues, you come to Léger still life paintings, beautiful, bold, colourful, abstract compositions. There is this feeling of layering and harmony intertwined with colour, form, objects, pattern and bold black lines. It is very harmonious on the eye and luscious to look at.

As you walk through, the works become more surrealist. In the thirties, Léger moved away from the man-made object. He spent time with the architect Le Corbusier and in the countryside of France where they found beauty in nature. Paintings by Le Corbusier and Leger are exhibited together within this exhibition. Le Corbusier was the most famous architect of his time and responsible for creating the Bauhaus style movement and creating many urban designs that helped in preventing difficult living conditions for residents in crowded cities. There are some similarities in Le Corbusier and Léger‘s works, but these paintings reject the idea of ‘reason’ and become more close to resembling poetic objects rather than anything that is logically identifiable.

The exhibition gradually ends with Léger‘s work becoming more figurative. Recreation, people and society become a new theme. There is a beauty and a sense of peace and harmony. The paintings are bold, sensual line drawings combined with abstraction, fluidity of line combined with cubist and flat planes, a sense of layering. Fabric design and textiles also become of interest. Léger starts to use universal meaningful subjects, acrobats and performers, a return to classicism and nudes. There is something sculptural and unified about the figures. A communist, Léger was vocal, portraying the workers and making statements about labour and society. His painting of a family scene depicts a pleasant outing with radiant blue skies, showing a sense of idealism and Utopianism.

The exhibition left me wondering about the future. The same questions being asked then are similar to what is being asked now. We seem to have now gone beyond and into that dystopian world that Léger was trying to challenge in his works. Just as he was inspired by past artists and writers, artists today are also still looking to the past. History has a way of repeating various arguments and politics throughout the centuries and responding to these ideas in new ways. But here we are still surviving or are we, a hundred years after Léger looked the machine in the eye.

In the final part of the exhibition, Léger is joined by two artists, Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho from South Korea, who speak a little about the similarities of Liverpool and their own hometown, a port that once thrived on the shipping industry. The two artists have collaborated on a project, ‘News from Nowhere’, that began in 2009 to explore the social function and role of art. This project is inspired by the utopian book, ‘News from Nowhere’, written by the Victorian artist, William Morris. Morris, while also an artist who has influenced our cultural and decorative style was also an activist and similarly these artworks look at ideas concerning capitalism and how we can return to nature and the land. I found this idea very interesting. I felt very similar in my views through art. Moon and Jeons’ works are collaborations with many other artists and musicians and filmmakers. It is interesting to see this word ‘collaboration’ again. We get so used to artists working on their own and in isolation to other artists that it is quite refreshing to see this approach taken for this work. It is their first exhibition in the UK and forms part of a whole which is titled, ‘The End of The World, 2012’, a two-screen projection that highlights the role of art in society through the depiction of an apocalypse and it’s the aftermath.’ Their films also depict well-known areas of Liverpool. Don’t forget to check out the iron manhole covers of which one is engraved with the slogan, ‘My future will reflect a new world’. There are two of these covers, one in the gallery and one outside in The Royal Albert Dock and what is rather interesting is that they both hint that what is the end of the world as we know it is also a new beginning thus giving us some renewed hope for the future.

And on that note, I conclude this review by changing locations although keeping on a similar strand of thought. It was suggested to me by a curator at Tate Liverpool to go and view the exhibition which is currently showing at FACT, Liverpool. The exhibition is called ‘Broken Symmetries’. This exhibition, in many ways, follows on from Tate Liverpool’s exhibition in the way it allows us to question how we view the world and our future, particularly in the way that Tate Liverpool has drawn attention to what role the artist plays in our current society. The exhibition at FACT is totally fascinating with artists creating innovative ways combining art and science to view the nature of our universe. Again, technology becomes an important aspect and relates back to ideas on the ‘age of the machine’ that Tate Liverpool has highlighted through the exhibition on Ferdinand Léger. ‘Broken Symmetries’, draws our attention to how ‘nature, as described by modern physics often defies common sense….’’

In this exhibition artists and scientists come together to create works of art. Artists have been invited to spend time at the lab, ‘The Collide International Residency Award, one of the core programmes of Arts at CERN since 2011, a collaboration with FACT for the last three years. The creative collisions that have developed out of this project are incredible. The exhibition points to how artists and scientists inspire each other and illustrate ‘the necessity of multiple perspectives’.

‘Cascade’ is an installation in three parts by artist Yunchul Kim. One part of this artwork captures particles from outer space. Each time these particles are captured, the machine sends a signal to a beautiful installation, the artist told me represented a tree. The signals from the particles send water through the branches and finally into the final part of the installation, a tubular sculpture where the water takes on a new form of kinetics yet again. Another artwork, a film, ‘The View from Nowhere’ by Semiconductor interestingly links in with the overall theme and questions science’s role in mediating nature. I loved Lea Porsager’s ‘‘Cosmic Strike’. It was so meditative and thought-provoking. The exhibition leaves you questioning our sense of reality and how we view and interpret the present and future

Do go and see these fascinating artworks, stop and reflect upon the entire experience from Léger’s ‘‘The End of the World’, to Moon and Jeon’s inspired works from ‘News from Nowhere’ to FACTS artist and scientist fascinating collaborations in ‘Broken Symmetries’ and you will see new possibilities in art and society, not only in how we view our present but of how we consider our future. Absolutely not to be missed!

Words: Alice Lenkiewicz Photos Courtesy Tate Liverpool © Artlyst 2018