At one point, perhaps somewhere around 1911, pictures decided they wanted to stop being a window through which you could see things already in the world – be it a landscape or an apple or a laughing cavalier – and simply be something in the world. They stopped representing and started being, either through abstraction or, as in the Cubism of 1911, showing a series of viewpoints in one moment.

To grant pure abstraction its utmost wish is to say that it is a painting in the same way a table is a table – there is nothing to it apart from that formation of shapes and colours on canvas or board. This is more metaphor than real within the picture – a splodge of colour is not really an object – but an abstract painting’s role in an interior does have this role in an interior. If a painting is just a painting then it can in turn be represented as easily as a table, landscape, or laughing cavalier. A photograph of a room with an abstract work on the wall would grant pure abstract painting its end goal of being purely something in the world.

Pictures with pictures in them are not uncommon. The mostly Northern tradition of painting Wunderkammer – collections of disparate objects built by the wealthy during the Age of Exploration – is full of paintings that have one or two paintings in them as subjects. The function of these paintings of collections was to better preserve and advertise them, as well as throwing objects into sharp juxtaposition to better get across the infinite variety of skills displayed by the true Renaissance Man. But as a side point, a painting within a painting does open one up to certain complexities. What do we make of the subject of the painting within a painting – those little hills and dogs that seem so nice and lifelike through the painting-window when we look at it on its own, but for all its own efforts at trompe d’oeil and Realism it is suddenly reduced to the status of illusion by being made part of another painting? The answer seems to be that it is sidelined and exposed. The actual content of the picture within a picture is partially ignored, at the expense of the content and more important illusion of the bigger picture. To a certain extent, for a picture to be an object in this way is for it to lose its status as a picture.

In some ways, given the Realism needed to give rise to this problem, it is obvious that a photographer would find their way into these questions sooner or later. German-born Florian Maier-Aichen, famous for his work as a landscape photographer, gives us five works in this exhibition at the Gagosian but these are quite out of the way of his usual output. They are photographs with a difference, involving a process of re-photographing to create two layers of images, pressed together on one plane. Of the five on show, I plan to talk about two.

Both feature a kind of freely looping white line that moves from being flat on the picture to being part of the illusion of 3-D picture space. In other words, it switches from being representational to being represented, mid-picture; from a three-dimensional looking form to an abstract form in two dimensions; from being a picture to being a picture of a picture.

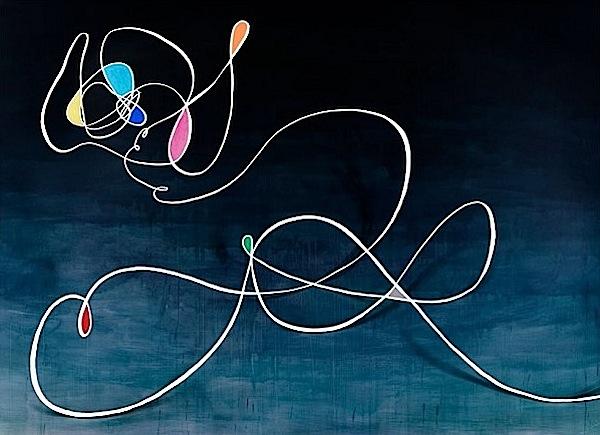

Florian Maier Aichen, Untitled, 2013, Chromogenic print, 72 7/8 x 92 11/16 inches (185 x 235.5 cm). Ed. of 6.

Both works are, unhelpfully, Untitled (2013), but one features a mountain range and the other doesn’t. The mountain range itself is beautiful and fit for a post-card. It is topped by a clear blue crisp-looking sky, with very sloped and snow-capped peaks of all about the same height, turning green about half the way down, with the photograph centred on a lush-looking valley with a river running through it, down to a small settlement in the bottom right corner (which may be something to do with hydroelectric power). One assumes there is a bridge over the river just round the corner of the right-hand mountain, because a road begins in the distance on the valley’s left side, disappears behind the right-hand mountain as it twists, then emerges on the right-hand side of the valley and winds its way down to the power plant.

The altitude the photograph is taken from, however, begins the riddle. It is taken from exactly the same height at which road begins in the distance between snowy hills and a particularly white part of the horizon. The road appears to begin out of thin air and, as it zig-zags almost uniformly, you begin to suspect that it has been drawn on, like a drypoint line. The apparent discontinuity between the road on the left and on the right heightens your suspicion, until it reaches the foreground (though it drops into shadow) and ends at the power plant.

The road forms a white line that, in the context of the landscape, is a three-dimensional looking object in the picture space. But the lower left hand corner of the entire photograph is blank, flat-colour blue, as though that area hasn’t developed. In this chunk, a single but prominent flat white line waves through the block colour with a kind of precise expressive looseness reminding you slightly of Chagall, but more heavily and more importantly the road in the landscape part of the picture. This demotes the landscape, somewhat, to being a picture within a picture – a representational section within a wider flatter composition – but because it is a photograph it cannot be denied the prominence that an oil painting within a painting could be. It is too bright, too real, too photographic. While the landscape photograph is revealed to be illusion – its road is re-made without shadows in the bottom left corner, on obviously flat two-dimensional surface – it also insists on being as real and three-dimensional as any photograph, which is very real indeed. The landscape photo becomes a photo of a photo (which, due to Maier-Aichen’s process, it is), but is no less photographic for that.

Maier-Aichen has his cake and eats it. The achievement is combining the realism of the landscape tradition with the object-hood of the Modernist tradition. The success is stating both at the same time – the object-hood showing us again the miracle of photography and the illusion of picture space that we have come to take for granted, and the representational aspect showing us the reality of the two-dimensional canvas that everyone knows and everyone finds difficult to remember. It doesn’t challenge our pre-conceptions, it highlights them; re-sharpens the basic sense of wonder that has been dulled by frequent exposure.

The other Untitled (2013) deals with a different aspect of the idea of picture-as-object, and in some ways is the ultimate expression of it. The basis of the fascination of pictures within pictures seems to be that a landscape can cast a rectangle shadow, as can a Cubist Braque (were it around to be in a Mannerist Wunderkammer). The weakness is that every painting casts the same kind of shadow, so in insisting that a painting is an object in itself you reduce it to painting’s fundamental monotony in some respects: no matter how good a painting is, it is still a bit of colour on some canvas or board; and to insist on painting-as-object is to perhaps give the canvas or board undue prominence.

If you look at one of Miro or Kandinsky’s abstracts, with flashes and lines and colourful detail everywhere floating in space, you are invited to consider the little details as objects in themselves, in space. This space, bounded by the canvas edges, throws a shadow, so although the abstract forms want to get off on their own someplace like real things, they can’t. They seem to be trapped in being only illusory – of being pictures within pictures. Maier-Aichen has found a way out of this illusion.

Untitled (2013) uses the same white doodle-like line as the landscape work, but this time in a wholly abstract way, especially reminiscent of Miró, although the occasional block colours slotted in between loops are more of a reference to a much less painterly form of abstraction and perhaps Mondrian himself. The background is dark blue at the top, making its way to light blue at the bottom, like looking out at the sea at night from a lit dock.

This creation of depth through gradations of colour would be a useful and common painter’s trick. However, this is a photograph, and looking closer you realise that what we actually have is a photograph of an empty room in a studio, with a wash of colour over the top, and the abstract white snaking line over the top of/cut into that. At the top edge of the picture, the darkness creates a flat back space, but as the background lightens and recedes into the picture space, the abstract line becomes a physical object in the photographic studio that looks a bit like Bruno Munari’s ‘Flexi’, complete with – yes – shadows.

The picture within a picture has managed it: to throw off it’s being a picture. This is not a situation where a frame or edge throws attention onto the canvas for being an object. What we have instead is an abstract picture whose abstract forms fulfil the ultimate goal of abstract forms: to escape painting; to be objects sufficiently to cast their own shadow or be photographed in a studio. The doodle has escaped the flat canvas of the picture surface to appear in a picture (of the picture) by itself, like a photograph of a wire sculpture. Although the work Untitled is still a picture of a picture, the picture being photographed is enough of an object not to be a picture, yet resolves itself into a picture as the background darkens at the top and the use of block colour grows more frequent, so as to flatten out the bigger picture at the top. It is a bright new achievement, flowing diagonally across the picture, and flowing up from sculpture to painting, and from photograph of a painting to just photograph, shaving off one dimension as it does so, autonomous as it wants to be, which is autonomy in itself.

**** – 4 Stars

Florian Maier-Aichen: ‘New Photographs’, at Gagosian Davies Street, 12 April – 25 May 2013

Main Image: Florian Maier-Aichen, Untitled, 2013, Chromogenic print 63 3/4 x 86 3/8 inches (162 x 219.5 cm). Ed. of 6.

Words by Jack Castle © Artlyst 2013