Often enough in his career, Jasper Johns has issued statements that say in effect: ‘Who am I? The truth is that I don’t think I really know the answer myself.’ Does this retrospective at the R.A. answer the question? Maybe not quite.

This exhibition offers a very complete survey of the lifework of one of the most generally respected of all living artists – ELS

Johns made his entry into the American art scene at a crucial moment in its post-World War II development – he arrived on the scene just as Abstract Expressionism, the first great statement of post-war American identity, was beginning to lose focus, but before the arrival of Pop Art.

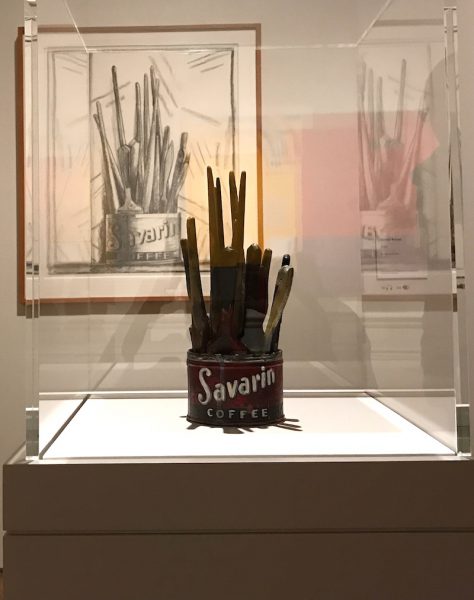

His work shared many characteristics with Pop but was equally obviously something different. His early work, which established his reputation, had a lot in common with Pop’s literalism. It was figurative, in the sense that it offered immediately recognisable archetypes – the American flag, maps of America, targets. It also offered very familiar symbols – numbers, presented in such a way that their identity was immediately apparent, not disguised in any way.

In his early work these basic, literal images were presented in a fashion that stressed, not their appearance as such, but the very seductive surfaces in which they were embodied. Much of this tactile seduction was due to Johns’ employment of wax encaustic, a technique employed by Ancient Greek and Roman artists.

It’s arguable that Johns’ first generation of patrons were seduced by aspects of his work that he had not perhaps originally intended. In particular, the flags and the maps seemed to be assertions of the dominance of American culture, in step with the hegemony that the victorious United States had established for itself. The paintings could also be read as statements of American patriotic values, as opposed to the values embraced by the Soviet Union and its satellites.

These readings were inevitable in the political context of the time, and have little to do with the Duchampian, post-Dada context within which Johns’ work has regularly been placed by a regiment of intellectual admirers. It is possible to wonder if the political interpretation of his work, which gave his career such impetus, was something the young artist intended, or whether it was happenstance, fortunate for him but imposed on what he did by people other than himself.

As Johns’ career developed, he seemed to move gradually away, at least for a while, from figurative representation. The ‘cross-hatch’ works of the late 1970s and early 1980s seem to be image-free, though on a second glance an image can sometimes appear – for example, the skull in the large drawing entitled Tantric Detail, which is included in the Royal Academy’s current retrospective devoted to Johns’ career.

This exhibition offers a very complete survey of the lifework of one of the most generally respected of all living artists, who now have a very long career behind him. A career during which he has received sustained support from both wealthy private collectors and from great museums worldwide. His work now regularly fetches colossal sums at auction.

In these circumstances, it may seem a little uncalled for to niggle, but niggling is, to some extent at least, an alternative job description for what is more politely called art criticism.

The organisers of the exhibition seem to have been aware of some possible weak points. The arrangement of the show is broadly chronological but careful not to be entirely so. The later groups of work, from the late 1980s onwards, are less striking than what comes earlier, and some seem downright feeble in comparison. They fail in two ways. Those based on the catenary curve made by a piece of string draped across the painted or drawn surface seem bleak and empty. The more figurative ones revive, not always successfully, aspects of long-established still-life tradition. Speaking of this latter, Johns has spoken of giving up the battle ‘to hide my personality, my psychological state, my emotions.’ ‘Eventually,’ he says, ‘it felt like a losing battle.’

As opposed to the Catenary series these figurative ones have a great deal of elegant charm, but one is left feeling that he hasn’t let go enough. One isn’t entirely surprised that this career summary tends to focus on what is now a long way off in time, rather than what is more recent.

What is here doesn’t destroy a great reputation, but the latter part of the exhibition chips away at it – just a little.

Words: Edward Lucie Smith Photos: Sara Faith © Artlyst 2017

Jasper Johns Retrospective ‘‘Something Resembling Truth” Royal Academy 23 September 2017 – 10 December 2017 Tickets £17 Visit Exhibition Here