Once you struggle through the fairly formidable Introduction to this biography – a chapter devoted to orientating the reader concerning Josef Albers’ major achievement, the long Homage to the Square series of paintings – this book offers a clear narrative concerning the life and work of one of the significant figures in the 20th century Modern Movement in Art.

Albers himself had less to say on the subject: ‘Art must do more than nature. That’s why it’s art.’

There are also things that it leaves out – for example, there isn’t much information about Albers’ wife Anni, a well-known artist in her own right, and a pioneering figure in the field of textiles. Anni Albers is currently the subject of an exhibition at Tate Modern, which runs until the end of January. Basically, what we learn about her here is that she was supportive throughout her husband’s career and that he was serially unfaithful. They were childless, though the biography hints that Albers may, in his American years, have produced a son with one of his mistresses. There is also the key fact that Anni was of Jewish descent – ‘the daughter of assimilated Jews who had had their children baptised as Lutheran’. Anni’s mother came from a cultivated background. Her own mother was an Ullstein, from an important Jewish publishing dynasty. Albers himself, non-Jewish, came from much further down the social scale. He was ‘a house painter’s son from a Ruhr mining town’. Anni’s Jewishness was the reason for their move to the United States to begin new lives when Hitler came to power in Germany. They made the move in November 1933.

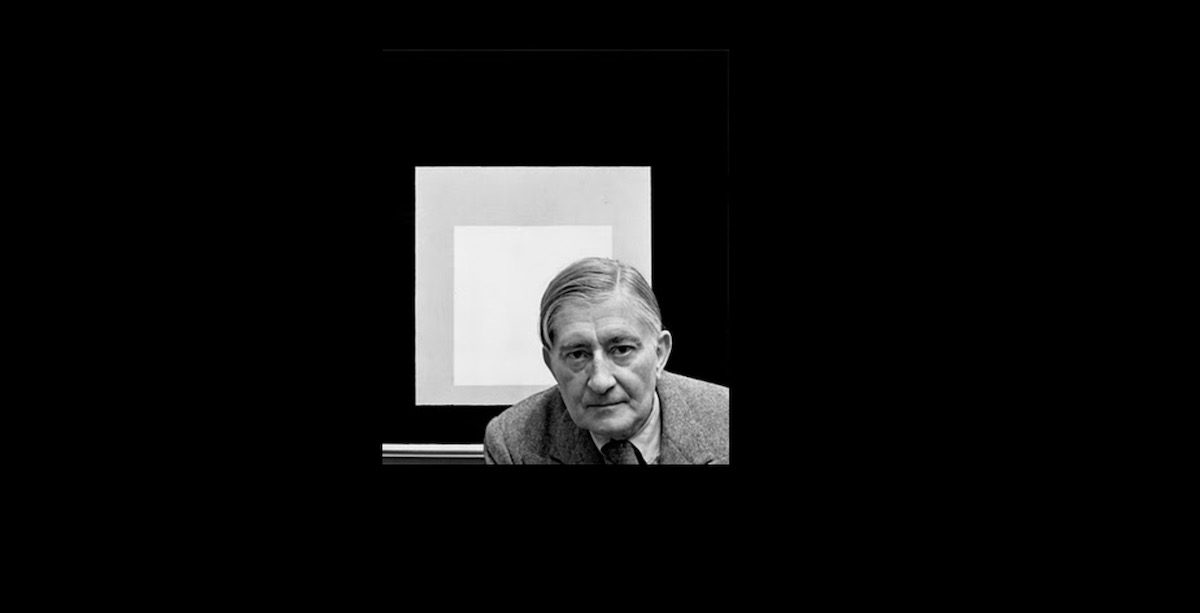

A preface to the book admits that Albers was in any case ‘an uneasy subject for biography… In a long and very public life, [he] managed to remain inscrutably private.’

He is also a strange subject for another reason, which is that he only reached prominence as an artist extremely late. After emigrating to the United States, he taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, then at Yale. He retired from teaching at Yale in 1958 but retained some connection there until 1962, when he was already 74. He lived on until 1976, and it was really only during this last decade-and-a-half that he achieved real celebrity.

Much of the narrative of the biography is concerned with the struggles Albers had with bosses and colleagues at the various institutions where he taught: at various incarnations of the Bauhaus – Weimer, Dessau, Berlin – then at Black Mountain College, then at Yale. He almost never had the upper hand at these institutions, and the politics within them seem to have been almost as ferocious in their own way as the struggles being waged in the tumultuous world outside.

Part of the problem in Germany seems to have been his lack of social status. His rivals for control at the Bauhaus were better educated than he.

Though much respected by some – though certainly not all – of his students in America, it was not often that Albers was top dog in the institutions that employed him. When he occasionally achieved this, it didn’t last.

In his German years, he seems to have been thought of as being something more of a craftsman than as a real artist. Part of this was due to the fact that he seems to have worked primarily in glass. His real legacy is the huge Homage to the Square series, made in America, from 1950 onwards. Using a minimal range of templates – squares within squares – he experimented tirelessly with colour relationships.

Art historians have had some difficulty in fitting these into the history of 20th-century abstract art. They have no relationship, for example, to the Black Square of Malevich, which long preceded them. Equally, they don’t fit comfortably into the story of Op Art, which began in the 1960s with artists such a Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley, nor with that of the Minimalism of the 1970s.

On an introductory page to the book, Richard Anuzkiewicz, one of Albers’ students at Yale, is quoted: ‘He liked the square for its simplicity. It was like a self-portrait. When you saw that square looking at you, it was Albers looking at you.’ This fits the Homage series into another recent (and to me depressing) story – that of famous painters who can find nothing much now to paint except themselves: Georg Baselitz, anyone?

Albers himself had less to say on the subject: ‘Art must do more than nature. That’s why it’s art.’

This new biography has a generous quotient of colour illustrations, which have obviously been carefully proofed. They suffer from three things. One is that printer’s ink is not in fact very good at matching paint, even paint on a flat surface. Another is that the severe reduction in scale greatly changes the effect. The third is that Albers clearly wanted his paintings to look subtly hand-made, however, disciplined the application of colour to a surface. The ‘handmade-ness’ can’t exist here, on this scale, in this medium.

A major question raised is less that of Albers’ position within the story of Modernism in art, which now seems secure, and more that of the continuing future of radical abstraction of this sort. If you shut out the world, what happens? The world, in turn, shuts you out.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith © Artlyst 2018

JOSEF ALBERS – Life and Work By Charles Darwent – Thames & Hudson £24.95 Order Here