This will be a great year of Leonardo celebrations because 2019 marks five centuries since the great artist died and Leonardo is now one of the great monuments of Western culture. Various countries are squabbling over who can do his memory the most honour. The chief contenders, of course, are Italy, where he was born, and France, where he died. Paintings securely by Leonardo are a scarce commodity. He made very few of them. Some, like his Last Supper in Milan, are now in deplorable condition. Others are not entirely by his own hand. His never-finished fresco of the Battle of Anghiari in Florence was long ago painted over, and we can only judge its effect from copies by later hands. The fact is that, though we refer to him as a significant painter, he was a very reluctant member of the profession. The same thing applies to Leonardo’s experiments with sculpture. He three times attempted to create a large equestrian monument, and on none of these occasions did he manage to finish the job.

The exhibition is beautifully laid out, and one is immediately impressed by the power of Leonardo’s draughtsmanship – ELS

The legacies of the other two artistic geniuses of the High Renaissance, Michelangelo and Raphael, look a great deal more materially solid. In Michelangelo’s case, we have his statue of David in Florence, his Pieta in St Peter’s in Rome, and his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. In Raphael’s, the paintings in the Vatican Stanze and all those Madonnas. Yet neither of these two artists have quite the glamour for today’s audience that Leonardo undoubtedly possesses. How did that happen?

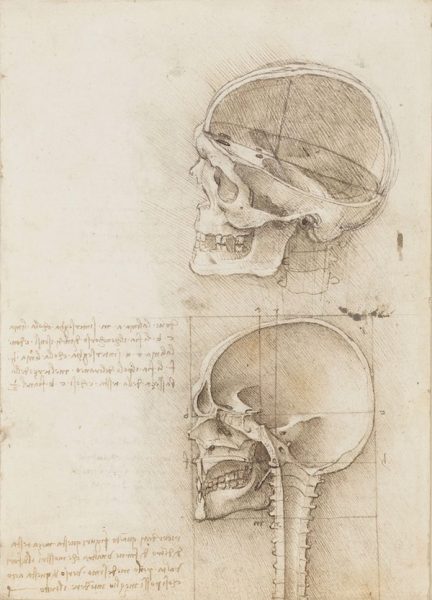

What we chiefly possess to judge Leonardo by now are his numerous drawings, which illustrate at first hand both his artistic projects and his explorations as a pioneering scientist. As an analyst of the structure of the human body, he was far ahead of his time. The problem here is that his explorations of this subject did not feed into the exploration of this subject that took place in the years after his death. They were not generally known about until they attracted the attention of scientists and historians of science in the 19th century. The significant discoveries were made all over again, in later years, without him.

It so happens that what is perhaps the best surviving group of Leonardo’s drawings, from all periods in his life, belongs to the British royal collection. They have been there since the second half of the 17th century when the Stuart monarchy was just recovering from the Civil War. Some 200 of them have just been put on view at the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace.

Drawings are fragile things. The opportunity to see these probably won’t occur again in a hurry.

The exhibition is beautifully laid out, and one is immediately impressed by the power of Leonardo’s draughtsmanship, displayed even in those sheets where he wasn’t particularly concerned to make art. His handling of his tools was exquisitely refined. His level of instinctive skill far outstripped that of his contemporaries. One notes, too, the things he investigated but didn’t get quite right – the mechanisms of flight in birds, for example. The mechanical devices he proposed for use in warfare didn’t go anywhere because the technology required to produce them wasn’t in his time available. Models of his contrivances have been made in modern times, using his drawings. In his lifetime, they didn’t get off the page.

Some of the most impressive drawings, made late in Leonardo’s career, show storms ad roiling waters. I haven’t seen this said by the authorities on is work, but what they occasionally suggest to me are Chinese ink-paintings of the same kind of subject matter. They offer proof of his powers both of observation and imagination. They also seem to be metaphors for his increasing disillusion with life. This feeling is echoed by some late portrait drawings of old men. One or two have been taken to be self-portraits, but this seems not to be the case. Yet it is not hard to see them as subjective – images not of individuals seen objectively, but of the artist’s own psychological condition.

Historical record suggests that Leonardo was a man of seductive charm. He had no fixed role in Renaissance society. Born a bastard, he attracted the patronage of powerful men. These connections took him out of Florentine society, and took him to Milan and eventually to France, where Francois I was his final patron. One gets the impression that he never entirely fitted in. He was homosexual, never married, didn’t speak or write Latin, which was the official language of learning. His problem was that these important patrons wanted to use his talents for projects of their own – to make portraits of their young mistresses, to design costumes for masques, to propose ideas for war machines that turned out to be not quite feasible. And to keep them entertained. He was never fully in charge of anything. Michelangelo and Raphael seem to have had more genuine independence, plagued as they both were with demanding patrons. He has succeeded with posterity, after a long wait, but in his own time, he was essentially a failure.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Top Photo: Sara Faith © Artlyst 2019 Additional Photos Courtesy Queen’s Gallery London

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing – 24 May – 13 October 2019

Marking the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, the exhibition brings together more than 200 of the Renaissance master’s greatest drawings in the Royal Collection, forming the largest exhibition of Leonardo’s work in over 65 years.

Read More