Lucian Freud – Real Lives is the first exhibition of his work in the North West for thirty years. Widely regarded as a master of modern portraiture, this exhibition brings some of Freud’s most iconic paintings, etchings and photographs, providing an ‘intimate glimpse into Freud’s Life.’ The exhibition focuses on portraits of friends and family, animals, most often pets of the sitters. Still, lives and nature play an essential role through Freud’s commitment to painting the human figure, painting plants, trees and inanimate objects.

Lucian Freud once said he wanted to paint drama in his pictures which is why he painted people

People have brought drama to pictures since the beginning. The simplest human gestures tell stories.’ Freud was German-born and was a leading figurative artist of the 20th century, a seventy-year career. He maintained a lifelong interest in the human face and figure, relentlessly exploring the possibilities of portraiture. Always painting from life, he was drawn to people he was familiar with, friends and family, expressing the cycles and transformations of his relationships. He expected commitment from his sitters, many of who posed for him for weeks, months and years. He sometimes turned his gaze inward, applying the same scrutiny to his self-portraits.

The exhibition pulls you in on quite an intimate level. I had never seen any of Lucien Freud’s work first-hand, so I wanted to see what stood out to me and what it was that many found fascinating. The exhibition combines oil paintings, detailed etchings, ink drawings, still life, landscape, plants, book illustration, inanimate objects and portraiture, including archival photographs stemming from the early years of Freud’s life up until his death.

In this exhibition, we are offered a glimpse into how people interested him and why he enjoyed painting them. There appear to be deep connections between his studies of close friends and family. My initial surprise with some of the works were that they were quite small. I wasn’t expecting this. I must have had a very different preconception of him as I imagined huge portraits for some reason, but they were primarily medium, small with the odd, very large painting. Maybe this was the case for this particular exhibition.

The exhibition begins with Freud’s early works, his painting ‘self-portrait, man with a thistle’, 1946. I could see that Freud’s interest in drama came through in this work. The thistle itself seems to have a sense of life about it, even though it has been picked and has died. And the self-portrait of Lucian Freud tends to be quite engaged with the viewer. There is an eerie atmosphere to this painting and you wonder what the relationship is between him and the thistle if there is one at all. However, the contrast of human and thistle creates an exciting tension.

As you walk on, you come to his ink drawing of Narcissus, 1948, a beautiful small drawing of this mythological person looking at his reflection, created in a different way than traditional approaches, literally splicing the paper with ink into two halves, in an abstract way to create the idea of a reflection rather than creating a realist effect. Freud creates this image of self-admiration in a simple ink drawing, almost abstracted, focusing on line, detail and tonal contrasts. I noticed Freud’s frequent attention to line and mark-making, the cross-hatching and shading. His drawing comes through as an essential aspect of his work.

The exhibition is divided into sections, allowing the viewer to gain a more focused view of his main themes and the people in his life. One of those people was Charlie Lumley. In his painting of boy smoking 1950-51, oil paint on copper, everything is so precise the structure of the face the detail of the cheekbones quite a powerful picture. Freud painted Charlie with a cigarette in his mouth. Freud became friends with the Lumley family when he lived in Paddington at the end of the Second World War. Charlie showed Freud the local nightlife and Freud helped Charlie when he ran into trouble with the law. They enjoyed each other’s company. Freud envied Charlie’s success with the girls. They both got on very well and became good friends at the time. Although a good portrait, one thing that didn’t appeal to me about this portrait was that Charlie had no neck, but instead, his head seemed to be positioned on an angled surface. I wasn’t sure what the point of it was, but maybe it worked without me being consciously aware, although I felt myself ultimately wanting to a see a piece of Charlie’s neck and possibly even a small corner of a lapel or polo neck jumper.

In 1948, Freud married Kitty Garner, who was daughter of the sculptor Jacob Epstein. They had two daughters, Annie and Annabel. They separated in 1952. Freud had difficulties with domestic life. There was a lot of infidelities and he was always unfaithful to Kitty, although she became a frequent model for him. ‘Girl with a fig leaf’. Etching on paper is a beautiful etching and a very haunting image of her.

There seems to be two ways that Freud looks at his sitters. I noticed there was a semi-fictional view of them where he distorts their features and turns them almost into what I felt looked like illustrations from a children’s book of fairytales that had then been enlarged and then there is this more raw and fleshy realist side to his work. It’s quite an unusual trait in an artist. I have not seen many artists jump from realism to what almost seems like surrealism within their life drawings.

Kitty Garner is portrayed in his painting, ‘Girl with Kitten, 1947’. This is a strange and haunting painting. Her distorted and idealised eyes are distant and gaze away from the viewer, along with her tight grip around the neck of her kitten, offering ambiguous insights into the psychology within this piece of work. Muted colours and precise lines contribute towards an eerie feel. The kitten gazes straight at us while she looks away.

Lucian Freud’s paintings are primarily portraits of people, objects, nature and animals. As you browse the exhibition, you become aware of the people that were significant in his life who became regular sitters. Many of his paintings depict portraits of people he had a specific relationship with or that he was particularly fascinated with. His paintings of people with their dogs and cats emphasise as much focus and interest in the animal as the person. He was quoted as saying, “You ask why I’m fascinated by the human figure? As a human animal, I am interested in some of my fellow animals: in their minds and bodies. “Animals, particularly dogs, appear in many of Freud’s works. Freud saw animals as portrait subjects in their own right and Freud saw people themselves as animals.

Painting, ‘Girl with a white dog’, 1950-51 oil on canvas. The composition is just wonderful, this sense of greyness, muted colours and so much psychology going on in this work, something dark, a sadness and again this surrealist feel. There seems to be an emphasis on the sense of isolation, nudity and this disconnection going on between them and us.

Again, Freud painted a ‘portrait of Pluto, 1988’ and in combination with people, as in double portrait 1985 -6, double portrait shows Freud’s friend Susanna with her dog Joshua and their bodies share the same platform. They were often painted as equals and shared the same level of intense scrutiny.

The more intense relationships Freud had with people the more interested he was in painting his sitters. In Freud’s portrait of his mother, 1973, he paints her in old age. She is looking away and it is as if you are looking down from above in terms of composition. There is so much detail in her face, the variety of colours to convey the different skin tones. Observing the painting, one notices Freud’s use of thick paint, bold line and varied techniques in mark-making, his attention to detail, the lines and wrinkles to convey the ageing process. Freud had a complex and challenging relationship with his mother. He found her favouritism of him during his childhood, compared to his other siblings suffocating and this made him feel distant towards her. But years later, when his father, Ernest, passed away, she changed in her behaviour and this broke the ice between them, creating a new bond between them. Thereafter, he began to paint her frequently. From 1972, he painted her over a thousand times and she became one of his most frequent sitters.

One of Freud’s romantic relationships was with eighteen-year-old Celia Paul, whom he met after he was invited to teach at the Slade school of fine art in 1978. They remained together for ten years and she posed for him throughout the years. She said that “Lucien said he had come to the Slade to find a girl and that girl was me.” They became romantically involved and were together for ten years having a son, Frank, who was born in 1984. Celia Paul often posed for him in many of her paintings. She was pregnant while posing for him for “girl in a striped nightshirt, 1983-5 oil on canvas. These paintings are quite small. The colours are interesting, the composition is lovely, the way you are drawn into the painting, the sense of distortion, the tones, the painterly approach.

I noticed Freud took an interesting approach to his still lives. He particularly enjoyed observing leaves and plants. There was something quite carnal and haunting about his still life. Freud would zoom in close up to his subject and paint from an untraditional and more close up angle so that one could see every detail of the plant. In his still life ‘Squid with Sea Urchin’ 1949, oil paint on copper, one can see his fascination to detail and his interest in the personality and inner world that encompasses objects, animals and creatures. His still life painting of a plant zooms in what would typically be seen as inessential detail, but it is this inessential detail that is often interesting to him. I felt the colour palette of his earlier works tended to have a CYMK feel about them.

Bella Freud is the daughter of Freud and Bernadine Coverley, a relationship that began earlier in his life. Bella was born in 1961.

Bella often posed for Freud and they formed a close father-daughter relationship. In the early 1990s, Freud helped her with her fashion label later in life. Freud was also close to Kai Boyt, the son of Suzy Boyt. He met Suzy at the Slade. She had four of his children. Although Kai was not his son, Freud treated him as his son and when Freud died, Kai was there at his side. These family relationships and this need to emphasise the full relationships and connections with specific family members seem to be emphasised throughout some of the written material. It seems significant people get a mention and it does leave you wondering about the relationships he had with those unmentioned. This, after all, is a legacy. The whole numerous ‘women relations’ scenario tends to echo the traditional construct of the free-thinking nineteen sixties male artist with the female muse. What happened to the voices of these female artists he met at the Slade who seem to disappear into becoming mothers and models? It would be interesting to hear these women discuss their own work and see their work exhibited in an exhibition.

Bella in her Pluto T-shirt. 1995, etching on paper, the use of very bold dark lines loosely drawn almost as if they pressed into the paper, detailed textures such as the chair and the trousers. I have to confess. I did not fall in love with Freud’s sense of line. My knowledge and intrigue of line has evolved historically from the school of Jean Dominique Ingres, a very controlled and smooth line. I enjoyed Freud’s textures and shading, but outlines for me suggest the solidity and framework of the body and my eye tends to reject broken and fragmented, bold outlines.

Etching on paper, Kai 1992, tends to be looking down in terms of perspective, not straight on with a focus on light and shade to create form, line to create character and personality the portrait set slightly from above where a whole multitude of mark-making techniques come into play.

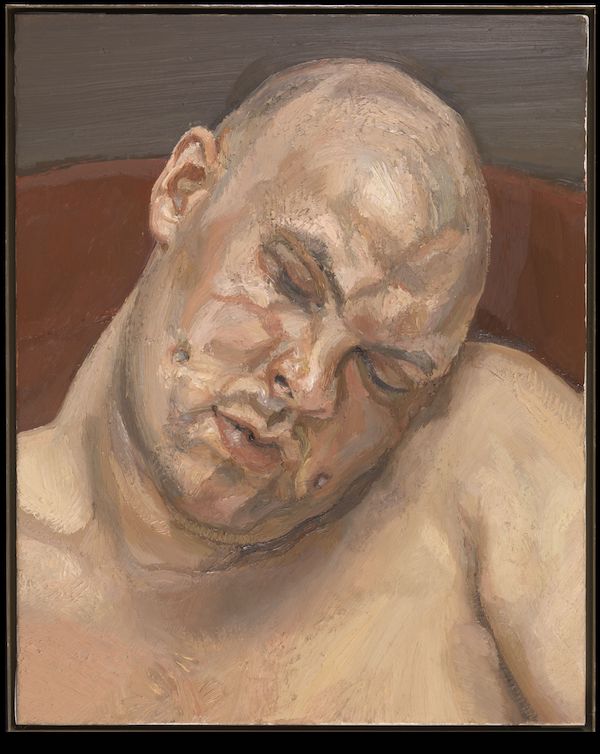

From the 1960s onwards, Freud focused on full-length nude figures. From the nineteen eighties onwards, he preferred to focus on larger nudes; all staged within the confines of his studio. His painting ‘Standing by the Rags’. 1988 is an example of the physicality of his style at this time. The model’s body is rendered in thick layers of paint. Freud liked his sitters to find their own poses that were also comfortable at the same time.

The colours of these later nudes are all quite fleshy with earthy colours, attention to every tone, blotch, bruise and rash, the artworks are quite muted, tones of white, blue pink, brown and black, a burnt umber feel, using a broad palette of earthy hues but also bringing in a full spectrum of colours to convey the feeling of the flesh. Freud painted a self-portrait of a significant milestone in his life. But he destroyed most of these portraits. Therefore the remaining self-portraits are an important indication of his working process. He often used mirrors to convey unexpected angles, such as his ink drawing ‘Narcissus’. Freud preferred to use mirrors for his self-portraits instead of his excellent friend artist Francis Bacon who preferred to use photographs. Many of Freud’s portraits look away from the viewer and seem lost in their own thoughts. Freud’s self-portraits, in contrast, gaze directly at the viewer.

Freud had a fascination with his sitters, particularly with their flesh and the way they moved. Many of his sitters allowed him the opportunity to explore the human figure in a variety of ways.

Portrait of ‘David and Ellie’, 2003-4 depicts David laying on his bed nude. Beside him reclines his white dog, Ellie. The painting is full of neutral and secondary colours, flesh colours, with earthy colours. A dying plant on a white and green stand. The man and the white dog reclining on a white bed. It’s quite a humorous painting in a way.

From 1990 until he died in 1994, Leigh Bowery was a regular model for Freud. Bowery was an Australian artist, club promoter and fashion designer known for his elaborate costumes and controversial performances. Freud had seen Bowery perform in the late 1980s and had a fascination for his physical presence. Commenting on the way Bowery edited his body was “amazingly aware and amazingly abandoned.”.

They worked together for five or six days a week, with Bowery working for several hours at a time. Bowery was free from his makeup and costume he was known for. He enjoyed modelling and the attention, with the bonus being the quietness; he felt he gained a different sense of himself. Freud also felt that Bowery had helped him understand how to convey movement in his figures.

Sue Tilly was a friend of Bowery and worked at his nightclub, Taboo. She was introduced to Freud by Bowery. She and Freud became friends and she posed for Freud, who was fascinated by painting her body.

Overall it was quite strange, a strange sensation to view this exhibition. I remember the publicity of Freud’s work during the 1980s at the time when my own father, Robert Lenkiewicz, who was an artist, was working on his giant portraits and nudes in his studio in Plymouth. I remember wondering what was so significant about Freud at the time and why was he gaining so much exposure in the art world compared to my own father, who was not as revered to the same extent and tended to be barked at by the art world. There was some rumour that one of my father’s models had had an affair with Freud and she was now working with my father as a model. All these rumours and gossip were rather intriguing for me at the time. That was the first time I heard about Lucien Freud. I had all kinds of images about Freud at this time and have to confess; I got the idea he was a madman. But maybe he wasn’t at all.

I felt a little emotional as I viewed the works. There were so many similar parallels running through Freud’s life compared to my father’s life, such as the stream of women, the fascination with the human form, the stories and controversy, the mirrors, the intellectualism, the intense mother-father relationship. Some of these similarities were uncanny. Even though very different portrait artists, they came from a similar time. I had never seen Freud’s work for real before. And now, here I was viewing these works for the first time.

The etchings are rather beautiful and exciting. His etching on paper, ‘Ill in Paris, 1948’, depicts a woman’s face lying upon a bed. You can just see the tip of a rose next to the bed frame. Just a very intimate portrayal, beautifully composed and does convey this idea of illness.

Freud’s sense of detail is quite incredible in his etchings. The painters garden, 2003 – 4. there is so much detail that it almost becomes abstracted, everything combined and condensed together. So much movement and different things happening all at once in this garden, the fence, the trees, the leaves and branches, the use of bold dark lines, loosely drawn as if pressing into the paper. This mass of detail and darkness, a mass of nature, the dark mayhem of a garden. I think this was probably my favourite artwork in the exhibition.

In his painting two plants, 1977-80 oil on canvas, there is this microscopic approach to Freud’s art. He zooms in very closely to the plants and we see the close up of the leaves. You don’t see this as a still life in the traditional sense. He is more interested in the intricacies of the intertwining of the leaves and the life that is going on underneath inside and in between these plants in the darkness and shadows rather than the actual formal distant view of these plants, something almost carnal and triffid about them it just creates this new world as if you are looking under the microscope of these plants.

Do go and view this exhibition at Tate Liverpool.

The exhibition continues on to Artist Rooms: Louise Bourgeois in Focus, 24th July – 16th January 2022, widely recognised as one of the most influential figures in modern and contemporary art. This exhibition focuses on her artworks centred on core themes of sexuality, isolation and motherhood. Not to be missed!

Review by Alice Lenkiewicz Photos Courtesy Tate Liverpool

TATE LIVERPOOL LUCIAN FREUD: REAL LIVES UNTIL 16TH JANUARY 2022