Artlyst has travelled to the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, which is presenting a retrospective of the great Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko – for a private tour of the show with the exhibition’s curator Doede Hardeman – forty years after the artist was last shown in the Netherlands. This is a unique opportunity to enjoy Rothko’s work, as the exhibition is only being shown in The Hague – and nowhere else. This is an extraordinary exhibition that follows the arc of the Abstract Expressionist’s career from the very beginning to its fateful end.

Rothko owed his worldwide fame to the ‘classic style’ of painting that the artist had adopted in the 1950s. Rothko considered that interaction with the viewer was of great importance, feeling that, for both the artist and the public, an overwhelming emotional experience was the most sublime form of inspiration, bordering on the spiritual.

Rothko was not the first abstract artist to attach importance to the spiritual aspect of art; artists like Mondrian and Kandinsky had also seen their work as a spiritual exercise. But he was the first to give a place of importance to emotion, at a time when abstract art was still fairly impersonal, the artist sought a revelatory emotional response from the viewer. The exhibition parallels Rothko’s work with that of Mondrian’s; the Gemeentemuseum is home to the world’s greatest collection of work by Mondrian, and by juxtaposing the artists we have a clearer understanding of the trajectory of Rothko’s artistic path.

Much to the artist’s annoyance early critics described Rothko’s work as ‘blurry Mondrians’; comparing both artists ‘classic styles’ – from the outset Rothko had the urge to set himself apart from Mondrian, leading to certain artistic choices – being accused at one point of stating that ‘anything created with straight lines was dead’. The artist’s denial of an evolutionary process from old works to latter pieces contrasted with Mondrian’s logical and linear journey to abstraction. Like Mondrian, Rothko began with depictive painting; with the artist’s first turning point occurring in the 1930s, with Surrealism being a similar catalyst for the artist, as Cubism was for Mondrian. The artist would go on to create works that focused on structural reductions of verticals and horizontals; ‘memory, history, or geometry.’ Rothko deemed as hindrances ‘between the painter and the idea.’ In many ways mirroring those concerns expressed by Mondrian.

The exhibition is a journey through Rothko’s development, and also reflects the artist’s personal journey; the Gemeentemuseum maps out the topography of Rothko’s career in an extraordinary arc of late-blooming success through to the artist’s abrupt end. The end of Rothko’s career had lead to ever-more sombre tones to the artist’s saturating blocks of colour, due to Rothko’s increasing depression.

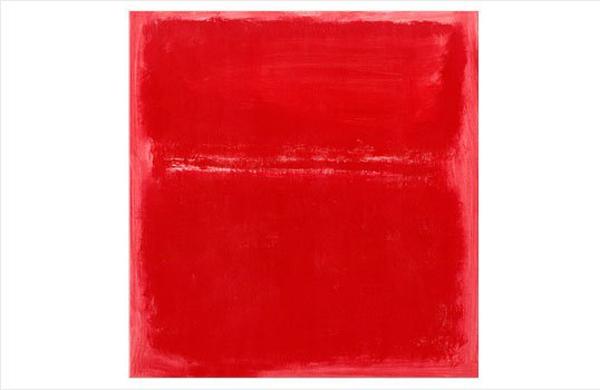

Yet the viewer is met with a startling surprise when viewing Rothko’s final work.

The canvas is not a sombre black painting but one of violent colour. ‘Untitled’ 1970 is a blood red canvas that in fact followed a series of increasingly dark and all-pervasive paintings. This violent blood-red work was painted just before the artist’s suicide, aged 66, and the colour of the work is noted as a signifier of Rothko’s intentions.

On February 25th, 1970, Oliver Steindecker, Rothko’s assistant, had found the artist in his kitchen, lying dead on the floor in front of the sink, covered in blood. He had sliced his arms with a razor which was found lying at his side. The painting is a powerful reminder of the fateful end of the artist’s career and life; the saturating sobriety of previous works are shed with a violent burst of ‘red anger’, life is soaked into that canvas; where Rothko had given his all.

Rothko’s fateful final work is displayed alongside the final piece by Mondrian, ‘Victory Boogie Woogie’ 1944. The work was never completed, and still has masking tape on its surface. These works are juxtaposed at the end of the viewers journey through Rothko’s paintings, a zenith in which it is apparent that both artists share a philosophical underpinning to their practices; yet with the tape still in place on the canvas – post Mondrian’s death from Pneumonia at the age of 71 – the work contrasts sharply with Rothko’s explosive demise on canvas – with a shock of blood red. The exhibition underscores the parallels and dissimilarities in the artistic practice of the first and second-generation pioneers of abstract art – even at their close.

Rothko was indeed a tortured soul whose death was one of self-imposed violence; this fact contrasts with a lasting capacity to affect the viewer in a becalming and reflective manner. The artist’s interests were expressive; Rothko wanted to capture the big emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, and doom – these were the artist’s muses; and they increase exponentially toward the end of this exhibition – resulting in a convulsive climax, and then nothing.

Rothko was no more; mental health issues had eclipsed his practice. The artist’s colour palette became darker and more sombre as time went on, the blackness of his feeling was an inescapable reality – until the sheer weight of depression, an ever-building pressure seen in the artist’s works as they darkened, culminated in a violent, convulsive release of brilliant red. A work of art born from the very feelings that ended Rothko’s life.

The artist stated “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” ‘Untitled’ 1970 is the final experience Rothko had; but the weeping of the viewer would not be through any religious experience, rather through the recognition of the demise of a great artist before his time. For those early critics that described the artist as a ‘colourist’ – Rothko’s final act had made them more than a little prescient.

Mark Rothko – Gemeentemuseum Den Haag – until 1 march 2015

Words: Paul Black © Artlyst 2014 photo courtesy of the Gemeentemuseum all rights reserved