Art created during a crisis can be a powerful catharsis for both artist and audience. Chinese American Martin Wong (1946-1999) once said, “Everything I paint is within four blocks of where I live.”

The California transplant moved to New York’s Lower East Side and portrayed the freewheeling sex, drugs, crime, racism and gay activism of his neighbourhood during the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Along with artists like Kiki Smith and David Wojnarowicz (also represented by the fabulous P.P.O.W gallery), Wong was a vital presence in the explosive East Village art scene. He returned to San Francisco and died in 1999 of AIDS complications. Like Wong, Aaron Gilbert uses realism to document today’s Covid pandemic and the devastating impact on his community and family. The thirty-year gap between the work is seamless, marginalized people still struggling to survive a modern plague in an urban environment. It’s a new millennium, but poverty and epidemics have not disappeared.

Both artists use intensely personal narration and an energized bold figuration to pay homage to communities of colour. Real people populate these paintings: from Wong’s huddled young couple, ”Dottie and Sharp” (1984), tenderly embracing in front of an abandoned tenement to the gloved Amazon workers in Gilbert’s “Conspirators.” Caught in a moment of intense unmasked conversation, the men are in front of a ubiquitous tower of cardboard boxes. These are the anonymous labourers who kept the city going, delivering packages while risking their own lives.

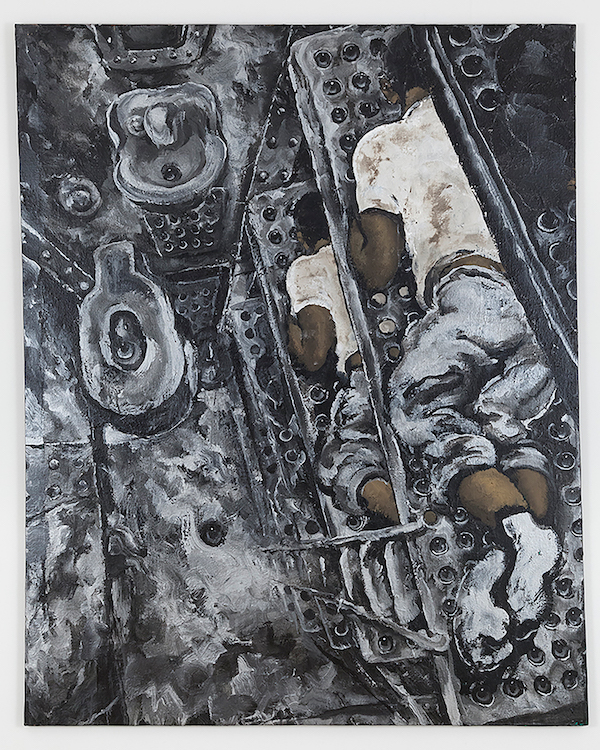

Wong’s homoerotic prison pieces are undisputed masterpieces. Hand-painted frames, expressive brushwork depict a rarely seen world of “three hots and a cot”, populated with incarcerated young men of colour. Forty years after their creation, images like “Prison Bunk Beds,” shows sprawled prisoners in bed, and the raw cramped geography of “Lock Up” (1985) rings as terrifyingly true as when first painted.

Gilbert’s “Nightshift” (2020) shows a sloe-eyed city transit worker receiving wrapped food on her plastic-encased bus. This is an inner-city version of a global pandemic as experienced by essential workers. Even the hospital in the background – the beleaguered Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn was one of the hardest-hit sites during the devastating spring months of 2020. Like Wong, Gilbert imbues his subjects with powerful dignity, though their red-rimmed eyes echo stress, overwork, and fear. The tender depiction of gracefully gender-fluid lovers, “Lupe, Aries”(2021), inspires with its compassionate vision.

Gilbert, who first suggested this remarkable intergenerational show says, “Wong created a new template for what we could ask and expect from figurative painting. I felt I had found someone whose personal relationship to his work was genuine.” Gilbert responds to that creative challenge with visionary realism. 1981-2021 creates a masterful creative dialogue, celebrating New Yorkers who are too often invisible while beautifully and bravely facing a front line crisis.

1981-2021 Martin Wong and Aaron Gilbert P.P.O.W. NY until 1 May 2021