Meek Gichugu’s No Erotic Them Say, included in this show, traumatised the imagination of Michael Armitage as a child. Armitage was friends with Rik van Rampelberg, whose mother, Chelenge, is a well-known sculptor in Kenya, and who, with her husband, put together a significant collection of East African art. Armitage saw this painting, which challenged everything he had been told about how to behave in society, at van Rampelberg’s home. The challenge it posed gradually opened his eyes to the power of art, as he could not rid himself of the image whilst initially finding it repulsive.

At the heart of Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict is an exhibition of East African artists whose work has influenced Armitage and around whom, through the van Rampelberg’s, he grew up. He has selected 31 works by six artists – Meek Gichugu, Jak Katarikawe, Theresa Musoke, Asaph Ng’ethe Macua, Elimo Njau and Sane Wadu – each of which played an important role in shaping figurative painting in Kenya and had a profound impact on his own artistic development. He has also selected works by three other Kenyan artists – Wangechi Mutu, Magdalene Odundo and Chelenge van Rampelberg – that are displayed in The Dame Jillian Sackler Sculpture Gallery, just outside the exhibition galleries.

The works chosen explore themes concerned with society, politics, sexuality, and religion, which are also reflected in Armitage’s paintings. His paintings’ colourful, dreamlike settings, play of visual narratives, provocative perspectives, and challenges to cultural assumptions enable exploration of history, politics, civil unrest, and sexuality. In discussing his debt to these artists, Armitage has emphasised the fact that he shares many of their socio-political concerns, in addition to the way they use Christian imagery and different aspects of local cultures.

The paintings of Asaph Ng’ethe Macua, for example, are inspired by his struggles with illness in his youth, by human nature and politics, as well as Christianity and traditional beliefs. Elimo Njau, who is known for major public commissions including a mural series of Biblical scenes, is an inspiration for having championed the arts of East Africa by founding the Paa-Ya-Paa (‘The Antelope Rises’) Gallery in Nairobi as the first African-owned art centre in East Africa. Paa-Ya-Paa became a key forum for local artists and intellectuals, hosting exhibitions, workshops, and debates.

Sane Wadu had a particular and strong influence on Armitage. Wadu was told he was insane to leave his regular work as a schoolteacher to become an artist and took the name Sane in response. He views art as not simply being work but, instead, a vocation that compels exploration of events, experiences, settings, and possibilities. His narrative paintings cast a critical light on society and religion leading Armitage to say that, from artists like Wadu, he learnt that ‘Painting is a way of thinking through something, trying to understand an experience or an event a little better and trying to communicate something of the problem to others.’

In his own works for this show, Armitage thinks through the tendency of politicians and preachers alike to simplify issues and make unrealistic claims; in particular, to promise paradise. In the run-up to the contested 2017 general elections in Kenya, he joined a local TV crew filming an opposition party rally taking place in Uhuru Park, Nairobi. Raila Odinga, the lead candidate of the country’s largest opposition party, promised to lead voters to Canaan, to the Promised Land. Such messianic promises, whether made on political, religious, or sexual grounds, are at the heart of images that undercut the hope of imminently achieving paradise.

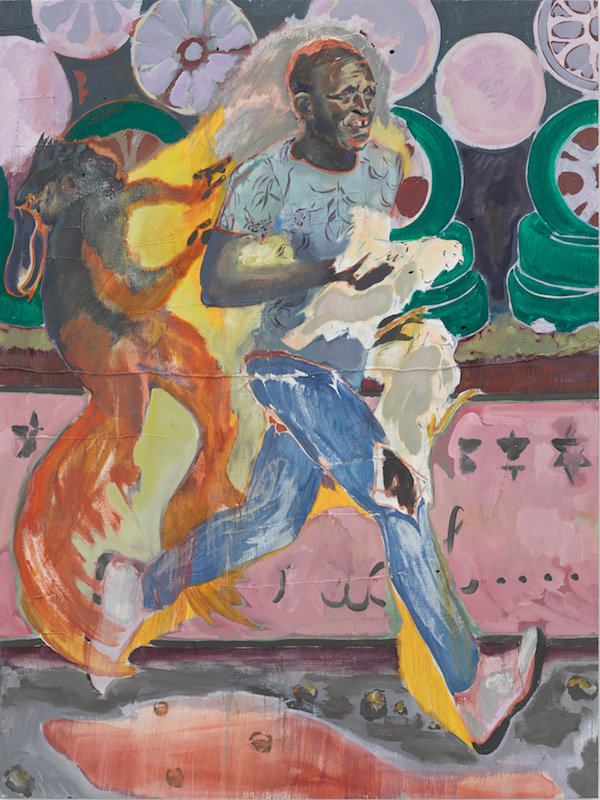

The atmosphere he experienced in Uhuru Park, and scenes witnessed, inspired a series of works exploring the links between religious rhetoric and politics which include The Fourth Estate and The Chicken Thief. These are works that reveal close observation of human expressions and gestures to explore power dynamics. Paintings such as Leopard print seducer transpose this exploration to the arena of sexuality as he shows us uncanny animals that behave and dress like humans to posture in ways that flaunt supposed sexual prowess. Armitage also draws on classical myths and tragedy, in his exploration of sexuality, power and the weight of social expectation in East Africa.

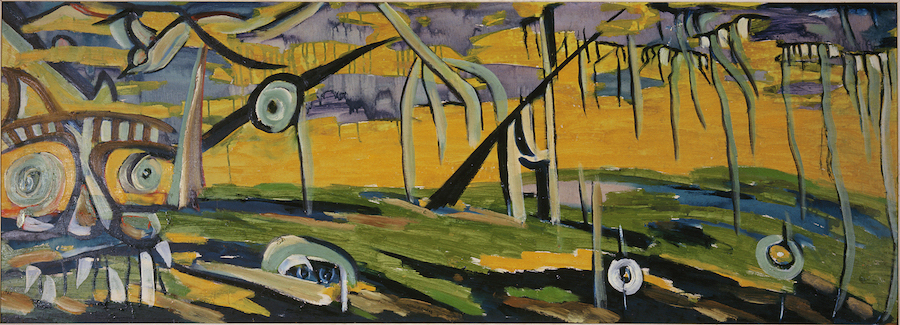

His monumental East African landscapes such as The Paradise Edict are among the most complex of his works exposing the reduction of Kenyan culture through exotic Western stereotypes to a mere fascination with breath-taking landscapes and wildlife. These are layered works with an overall abstract unity within which figurative motifs, primarily drawn from Kenyan culture but also referencing Western art, blend and clarify through a mix of detail and sketch. Ghost-like, minimally sketched figures blend into lush landscapes alongside developed figures that initially catch the eye, drawing the viewer in to see further and deeper within each magical image. The multiple layers of these landscapes in which the violence done to the ghostly figures betray the underlying tensions found within and beneath the surface’s paradisal clichés. Armitage’s sophisticated and multi-layered narratives reveal a more complex history and reality that powerfully traumatises minds in just the way that he experienced when viewing No Erotic Them Say on the wall of van Rampelberg’s home and wondered why anyone would have it in their living room.

Elimo Njau, Dream Landscape, 1968. Oil on canvas, 47.5 x 132.3 cm. Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt am Main © Elimo Njau. Photo: Maria Obermaier.

Drawing on contemporary East African art and European art history while working between Nairobi and London thereby bridging artistic traditions, Armitage combines motifs, approaches, and themes from the works of Katarikawe, Gichugu and van Rampelberg as well as Titian, Francisco de Goya, and Paul Gauguin. Having learnt from Wadu that painting is a way of thinking through something, he now recognises, as he expresses to Don Handa in a conversation recorded in the exhibition’s catalogue, that ‘Artists have been exploring, basically, the same ideas for thousands upon thousands of years, and it’s the “human experience”.’ This is the lineage and tradition of which Armitage is now part; a lineage he has joined just over 10 years since graduating from the Royal Academy Schools.

By founding Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI), a non-profit visual arts space dedicated to the growth and preservation of contemporary art in East Africa, curating exhibitions of East African art, and creating his own thoughtful and thought-through multi-layered works, Armitage is carving out a substantive legacy for himself within the lineage of art and artists whose value and values he examines and promotes.

Top Photo: © Artlyst 2021

Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict, Royal Academy, 22 May — 19 September 2021