The Monochrome show at the National Gallery has gained less coverage and generated much less enthusiasm that the current Living Gods show at the British Museum. The Guardian, for example, sums it up thus:

‘This peculiar exhibition shirks black and white certainties in examining monochromatic art ad painting, but why is there no room for Yves Klein, Robert Ryman or Chinese painting?’

Monochrome, as a term, means just ‘single colour’

The use of monochrome in art is a big subject – it goes back a long way – and one shouldn’t be surprised that some contemporary favourites have been left out. The topic also covers a lot of ground in chronological, if not, as the Guardian’s reviewer points out, in geographical terms. The time scale, too, could possibly have been expanded.

How about classical Greek vase painting: black figure, red figure white figure? Greek vases tell us a very large part of what we know about Greek art in two, as opposed to three, dimensions. The representations we find there are largely monochromatic. The additional paradox there is that much of the Greek sculpture that has come down to us – work in marble rather than in bronze – was originally painted, whereas we, confronted with it, tend to think of it as paradigmatically white. Time has stripped the colour away.

In antiquity, therefore, what we think of as being the established roles of colour – colour the province of art in two dimensions, monochrome dominant in three-dimensional art – were to some extent reversed.

In fact, despite its limitations, I found the National Gallery show much more informative than the one at the B.M. No tremulous sotto voce injunctions here to feel some kind of mystical vibe, certified by a link to one or other of the world’s all too numerous religions. And certainly, a great deal more that it is less of a strain to categorise as art. The N.G. does actual art, not souvenirs.

The use of monochrome in art from the 15th century onwards to our own time has served various purposes. It was used for religious reasons – for example, for representations designed to be shown in Lent. It was used to make preparatory modelli, before advancing to full colour. It was used as a quicker less laborious way of producing what looked like reliefs carved in stone.

As the presentation advances into the epoch of Modernist, then fully contemporary art, one notes how the uses of monochrome – in this case of black-and-white. Monochrome, as a term, means just ‘single colour’, not necessarily black.

One of the most significant works included is one of the four versions of Malevich’s Black Square. Malevich claimed when he produced the first of these that he was ‘freeing art from the dead weight of the real world’. He also arranged for the painting to be shown high up in a corner, in the position usually occupied, in traditional Russian households, by an icon representing the Madonna, or some patron saint. In fact, the painting can be a read as an invitation to worship the mystery of the void. It would seem equally at home in the Living Gods show in the British Museum. Thrown out through the gallery door, mysticism and mystagogery return through this small window opening into a vast black firmament. It’s no accident that, hanging nearby, there is also a canvas by Vija Celmins representing a night sky – an expanse of blackness adorned with a myriad twinkling points of white.

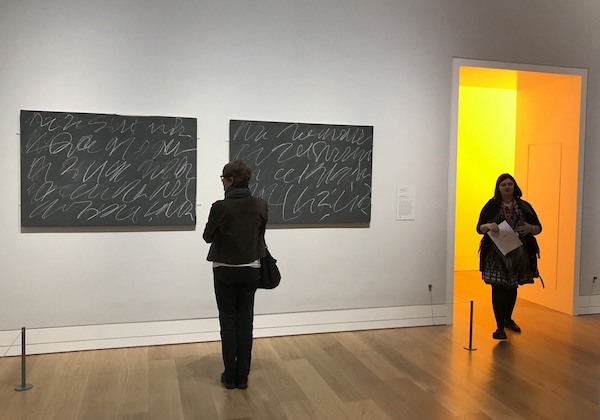

The show concludes with a large empty room – a light installation by Olafur Eliasson. The catalogue claims that by:

‘Using single-frequency, sodium-yellow lights to suppress every other colour in the spectrum, Eliasson transforms the inhabitants of his exhibition space… into shades of black and white.’

This doesn’t work quite as drastically as the catalogue claims. For me, there were still faint, haunting hints of other hues. When I was there, visitors to the exhibition loved it. A wall notice encouraged – rather than forbade – them to take photographs, and they were happily making selfies on their phones.

Today, audience participation is very much the name of the game in museum shows. You can whizz off from the NG to sample those jolly swings not so far away in the entrance hall of Tate Modern. More selfies, please! Apple has just introduced a very snazzy new version of the iPhone, which will be perfect for the purpose.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2017

Monochrome Painting In Black And White National Gallery 30 October 2017 – 18 February 2018 Visit Here