Nam June Paik (1932-2006) was a Korean-born artist who lived and worked in Japan, Germany and the United States. He played a considerable role in the international avant-garde. His first solo show, Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, was staged in Wuppertal Germany in 1963. Among his collaborators during the course of his career were Joseph Beuys, John Cage and Merce Cunningham. He was also a member of the Fluxus group in the 1960s, though the founder of the Fluxus collective George Macunias fairly soon expelled him. His crime was his participation in Stockhausen’s experimental musical drama Originale, which Macunias was intent of boycotting.

The technology is very soon and inevitably going to outstrip what they do – ELS

In 1993 Paik and the German artist Hans Haacke were invited to jointly represent Germany at the 1993 Venice Biennale – this despite the fact that both artists had been based in the United States since the mid-1960s. The German Pavilion won the Golden Lion award. One could hardly hope for a better avant-garde pedigree of the Cold War period.

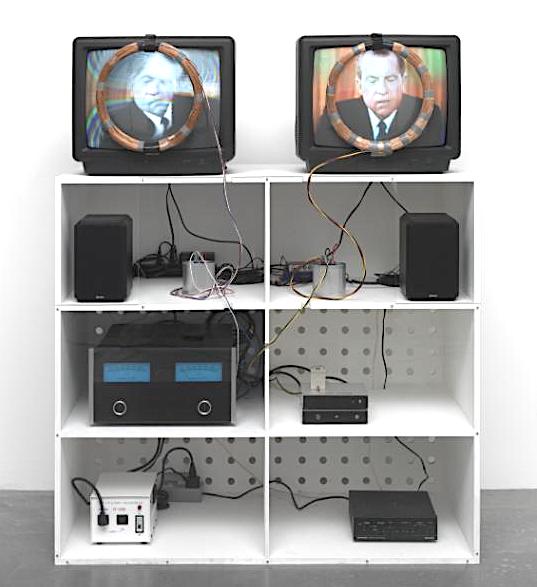

The difficulty is, as this exhibition at Tate Modern demonstrates, that technology has moved on very rapidly since Paik was active. Much of the technology looks clunky – the boxy television monitors seem archaic, compared with today’s flat screens. The robotic figures that feature in some of the galleries seem simultaneously playful and grandfatherly. They have the air of having been improvised from a boxful of spare parts – components originally produced for quite different purposes.

This kind of thing seems inevitable when artists try to make art in step with a fast-moving technological society – the technology is very soon and inevitably going to outstrip what they do. In this sense, the Paik retrospective is a show about the recent past of supposedly avant-garde art married to technology, rather than being one about the way that the avant-garde is now. I tended to wonder if the curators of the exhibition had completely taken this factor on board.

Despite the revolutionary (for their time) and often contentious crew of artists and sound-artists whom Paik collaborated with during his career, the exhibition is, by today’s standards rather blessedly non-political. During the greater part of the period when Paik was active Russia was still Soviet, Germany was still divided, feminism was a much smaller force in the art world than it is today, and the initials LGBT had not made their way into full use. It is not simply that technology has changed radically – it is also that social and political preoccupations have changed too.

The problem with technological change in the sphere of art is that, with rare exceptions, the changes tend to be irreversible. Once artists have learned better and more sophisticated ways of making artworks, they use them. Or else they take a step back from the technological opportunities presented to them and insist that art must remain handmade – the product of skills inherited from a pre-technological past.

The best things in the Paik show are the rooms with projections on all the surrounding walls. Visiting these, one does, however, tend to chafe at the clutter of metal poles supporting projectors that occupy most of the central space. This large, ramshackle construction tends to squeeze you too tightly against the walls, with their shifting array of colours, that you are supposed to be looking at. If you could press a button and tell those poles to vanish the effect would be a lot more impressive.

Words/Top Photo Edward Lucie-Smith © Artlyst 2019