This handsome soft-cover catalogue published by Thames & Hudson for the British Museum was intended to commemorate an exhibition that hasn’t in fact taken place, due to the coronavirus. It offers illustrations of Piranesi drawings, with a few subsidiary illustrations of Piranesi’s prints. The drawings are all from the BM’s collection, nearly all from a single source, the collection of John Gott, Bishop of Truro, sold by Sotheby’s in 1908. The sole exception – the only drawing of a figure – was purchased by the BM in 2008. All the other drawings are architectural.

Piranesi is a fascinating figure in all kinds of ways

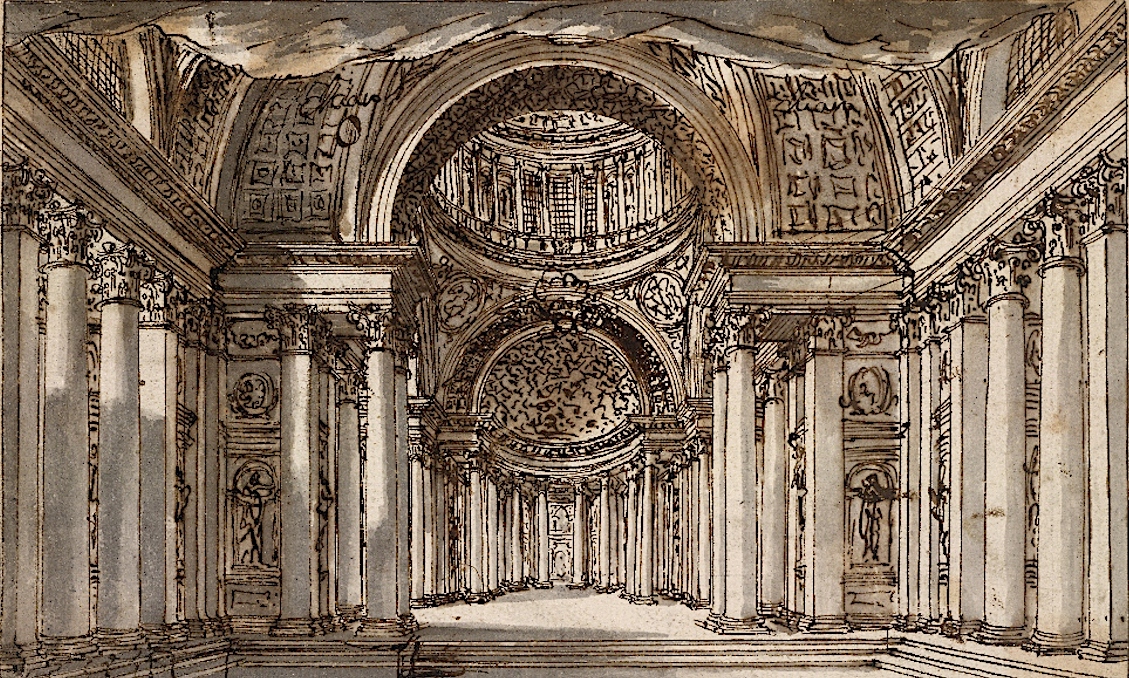

He was an 18th century Venetian, and it seems clear that his original ambition was to be an architect. Frustrated in this, he became an architectural draftsman and a prolific maker of prints illustrating buildings both real and imaginary. He settled in Rome and published numerous editions of these, which echo the splendour of Roman Imperial architecture. One significant influence on his work was theatrical designs, especially those produced by members of the Bibiena family.

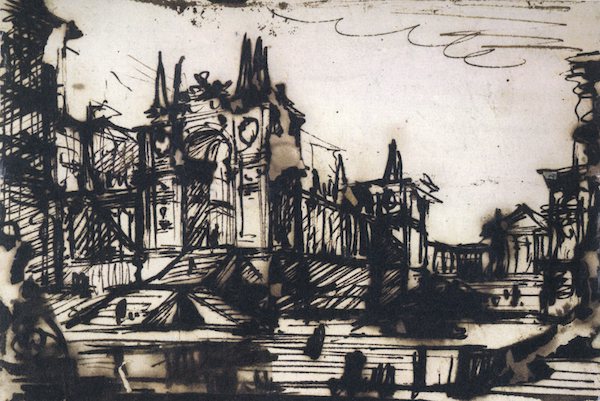

If one looks at his work, one can also see several other influences at play. Though he was an enthusiast for the world of classical antiquity, he was hostile to the intellectual current of his time, which had started to promote Greek art of the classical period as opposed to that of Imperial Rome. In fact, he preferred to believe that the Imperial monuments he saw all around him were descended not from the Greeks, but from the Etruscans, who were native to Italy. The drama with which he imbued his architectural scenes was inherited from the Baroque art of the 17th century, via the theatrical tradition of his own day. On the other hand, his fascination with ruins links him to just-burgeoning Romanticism. This influence is particularly marked in the series of prints called Carceri or Prisons. One can even see him as being, in some of his more fantastic designs, a precursor of Surrealism.

The catalogue offers one an opportunity to think at leisure about all these things. It also provides something else, though it maybe takes a moment or two to recognise it. Some of the drawings reproduced are, despite the grandiosity of their subject matter, very small. The catalogue reproduces them more significant than they actually are – thus reversing what usually happens with art books. In which case, what does one see more: looking at the drawing actual size in a gallery, or looking at it, as here, on a page in an illustrated art book?