I wasn’t sure what to expect from Radical Landscapes, but it went beyond my expectations. As usual, Tate Liverpool has developed a thought-provoking and in-depth exhibition on this subject. It’s a massive archive and tribute to many activists and artists, such as the Women of Greenham Common, the protests, eco-feminist politics, the anti-nuclear movement, a selection of highly regarded established artists, and even tributes to hiking groups and campaigns to save the land. This is a significant exhibition showing a century of landscape art and people’s reactions to nature, revealing “a never before told social and cultural history of Britain through the themes of trespass, land use and the climate emergency.”

This is also a show about the social and cultural influences of the recent pandemic and the sudden rush to be with nature and the landscape. The exhibition draws on the conflicts over the centuries between owned land and public access and how politics in the past and even Brexit have changed our perspectives on land and ownership, the idea of what defines ‘Britishness’, a sense of England ‘belonging’ to us, bringing us back to this idea of who really ‘owns’ the land and who owns England? Common land is always becoming owned and enclosed, raising intrinsic questions on the concept of ownership.

The pandemic provided a phase of reflection, encouraging and inspiring people to participate in the great outdoors once again, promoted during the first and second world war, working on the land, hiking, camping and country living. This also gave women, in particular, an opportunity to take on new roles, such as working as land girls who did the jobs men couldn’t do during the Second World War and the suffragettes who fought for the right to participate and occupy space on an equal standing to men. So it seems the rights of the land can also be very much interwoven with human rights and identity.

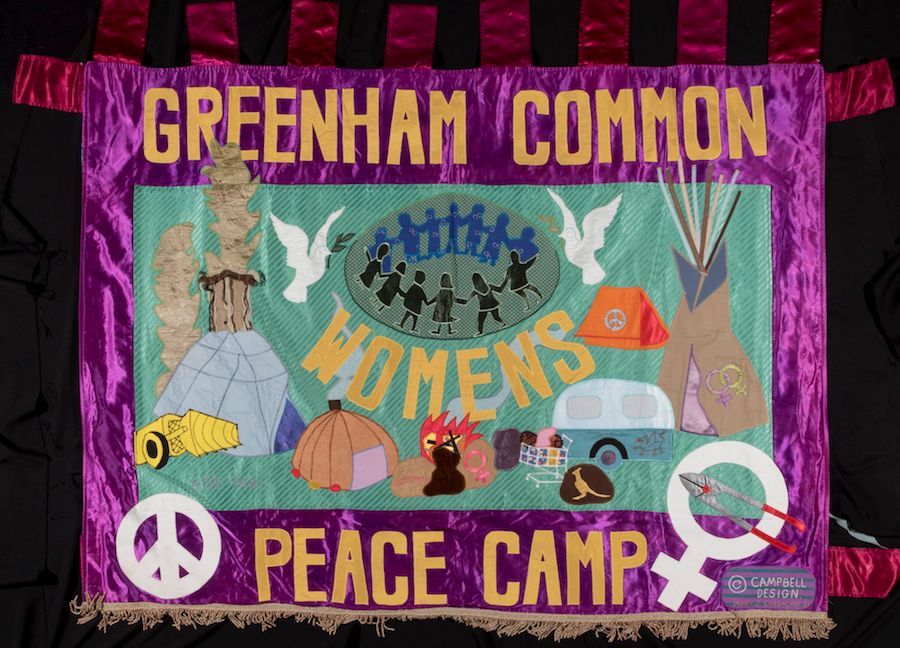

The show begins with the idea of nuclear disarmament and the Greenham Common protests. As you start to digest this movement of people throughout history campaigning to reclaim the rights of the land, you begin to see how colonialism and capitalism have created a language that has gradually over time, affected our human rights and spiritual understanding and connection to the rural landscape.

Creativity was at the heart of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp. Banners, Sculpture, Performance Songs, and Poetry zines to convey their messages came out of the movement, forming a passionate archive of art and creativity, a form of expression for the women at this time and for us to look back on.

The installation, ‘In Our Hands’ 1982-1984. by Tina Keane, an artist and activist was created during the Greenham Common Peace Camp. The video installation shows us recorded material of the peace camp through gently moving inverted hands. Films of women talking, singing and protesting at the fence are intercut with a spider weaving a web amidst lush greenery.

The cobweb became a symbol at the time for women and represented interconnectivity. “Some activists wore giant woollen webs, entwining themselves with the fence around the base and making their arrest by the police more challenging. “Women from Liverpool are shown in photographs of the Greenham Common peace camp travelling to Berkshire at the height of the cold war.”

The exhibition encourages us to think about our traditional concepts of landscape, the idealised version of nature and rural life, for instance, John Constable’s painting of Flatford Mill, 1816-7, a painting of the River Stour in Suffolk. These idealised paintings of landscapes by Constable were, in reality, a stark contrast to workers at the time who were being pushed away from the land “through the enclosure and the mechanism of agriculture.” Constable’s paintings have always expressed the epitome of “Englishness.” and have even been introduced into the school curriculum where they have been taught in colonised nations throughout the British Empire.

In light of the landscape and nuclear disarmament, The artist Peter Kennard has reinterpreted Constable’s painting and changed it to “Haywain with Cruise Missiles”, highlighting the ‘absurdity of nuclear war and the incongruity of placing modern weapons, capable of exterminating civilisation” in the hay cart of Constables painting, transforming it into a “vehicle for megadeath.” This concept reflects the convoys that brought the cruise missiles to Greenham Common, whose protestors lay down in front of them to hinder their progress.

There are some incredible and fascinating works of art, photography and textile art from the Greenham Common Peace Movement. The photographs are interesting and portray a fascinating portrait of the time.

Format Photographic Agency was a women’s only photographic agency that existed between 1983 and 2003,” It offered a platform for female photographers to develop their creativity and careers.” Their work documented critical political events. Photographs taken at the Peace Camp at Greenham Common as well as trespasses of other military landscapes are exhibited from the 1980s, such as ‘USAF Greenham Common, Protest at Main Gate, July 1983’ by Brenda Prince. and ‘Women Cut their way into Base, 12 May 1984-1984 by Joanne O’Brien. Thalia Campbell’s Textile artwork, 1982, was a vibrant and skilful piece of protest art using appliqué and embroidery.

I can remember seeing the women of Greenham Common protesting on TV in the early eighties!

Militarised landscapes are significant in this exhibition, depicting land that has been used for war and weapons. There is even a video by the art critic John Berger from ‘Ways of Seeing’ 1972, an examination of Thomas Gainsborough’s painting, ‘Mr and Mrs Andrews’, 1750, exploring expressions of power and wealth in European landscape painting and private land, challenging Kenneth Clarke’s more idealised critique of this painting.

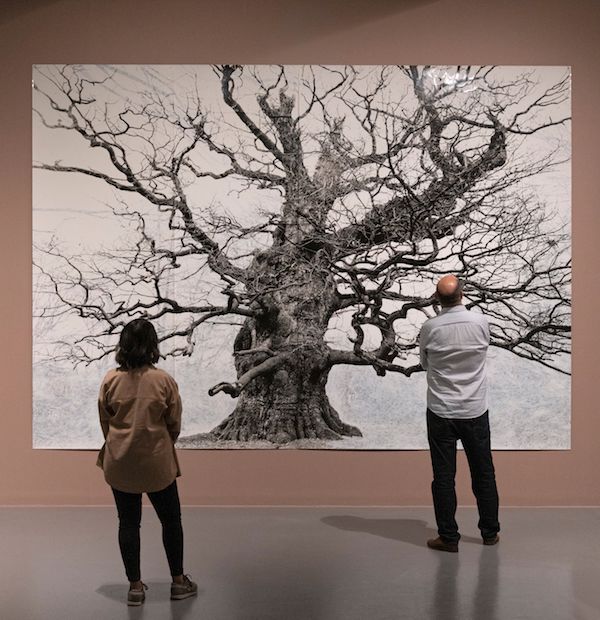

The idea of the oak tree as an ancient symbol of communal power interweaves throughout the exhibition in photographs and paintings and draws on symbols of Englishness, conservation and protection. “An artist’s depiction of a particular landscape can become a symbol of Englishness.”

‘An English Oak Tree’ by Stephen McKenna is a sizeable iconic painting displaying this beautiful tree in its glory and symbolism. Tacita Dean’s ‘Majesty’ 2005 depicts one of England’s largest and oldest complete oak trees. These are beautiful and fascinating.

The female goddess earth movement and pagan religions are another significant response to the landscape and are explored in paintings and ancient standing stones, paintings of The Goddess such as ‘Earth is our Mother’ by the Swedish artist Monica Sjöö. Monica joined the peace camp and was an early exponent of the Goddess Movement.

The exhibition highlights how the land has long been an issue of being privatised and taken away from the public. People have consistently campaigned to keep their rights regarding freedom of movement throughout the rural landscape. The exhibition shows how history repeats itself and how we are constantly fighting for the same rights throughout history. Capitalism and war are usually the culprits in destroying land and making a profit.

The exhibition continues to explore an emerging environmental consciousness and also explores ancient land rights. The interweaving of nature, the oak tree and natural landscape, the ongoing campaign against pollution, the need for protection and a deep engagement with landscape history. The idea is that we all have a collective responsibility for the land.

The show leads into the 1990s and the road process movements, campaigning and protecting nature and depicts shocking photographs cutting through beautiful countryside to extend the M3 motorway. 1993. Photographs by Nigel Dickinson explore this destruction of our land.

It’s impossible not to bring up current campaigns and protests that are currently taking place in Liverpool, such as the Rimrose Valley Campaign in Sefton. Protestors and creatives have taken inspiration from the valley to express their voices and respond to the idea of the destruction of the land and nature in response to the proposal of a motorway being built through this important green space. However, it’s also worth noting how people within this campaign have responded politically and creatively to the land, encouraging educational, spiritual and physical engagement with the outdoors and nature, another example of how creativity blossoms out of conflict and protest and how green space is also critical, not only to the community in our current daily lives but also for people near and far during the pandemic.

The exhibition also explores colonialism of the Caribbean and the relationship between internationals and how they perceive and relate to the land as in ‘Oceans Apart’ by Turner Prize-nominated artist Ingrid Pollard, “juxtaposing historical imagery of British colonisation and slavery with personal family photographs, showing how personal narratives speak to broader histories.”

The show is fascinating and a feast for the eye in terms of diverse art mediums and approaches. It concludes with an immersive installation, ‘Back to the Fields’ 2015-2022 by Ruth Ewan, bringing the gallery to life “through a living installation of plants, farming tools and the fruits of the land. Taking up a whole room, the artwork brings to life The French Republican Calendar” used from 1793 until 1805, objects which each denote a day of the year.”

“Radical landscapes pose questions about who has the freedom to access, inhabit and enjoy this green and pleasant ‘land’. You will find a diverse mix of approaches and responses. You can take what you respond to from this exhibition, but its diversity also provides the opportunity to learn from others.

This exhibition is vital to us questioning our current environment and how we move forward in the future.

Radical Landscapes – Tate Liverpool – 5 May – 4 September 2022

Words: Alice Lenkiewicz Photo: Top and Insert 1 Radical Landscapes, installation view at Tate Liverpool. 5 May–4 September 2022. Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)