To stage a major Rodin exhibition in 2021, the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante is particularly appropriate as Rodin reread the Divine Comedy so often, he kept it tucked in his back pocket, while his monumental, sculpted doors The Gates of Hell, inspired by The Inferno, were the source for many of his most well-known images.

Rodin learnt from Michelangelo’s ability to show internal pain and suffering – JE

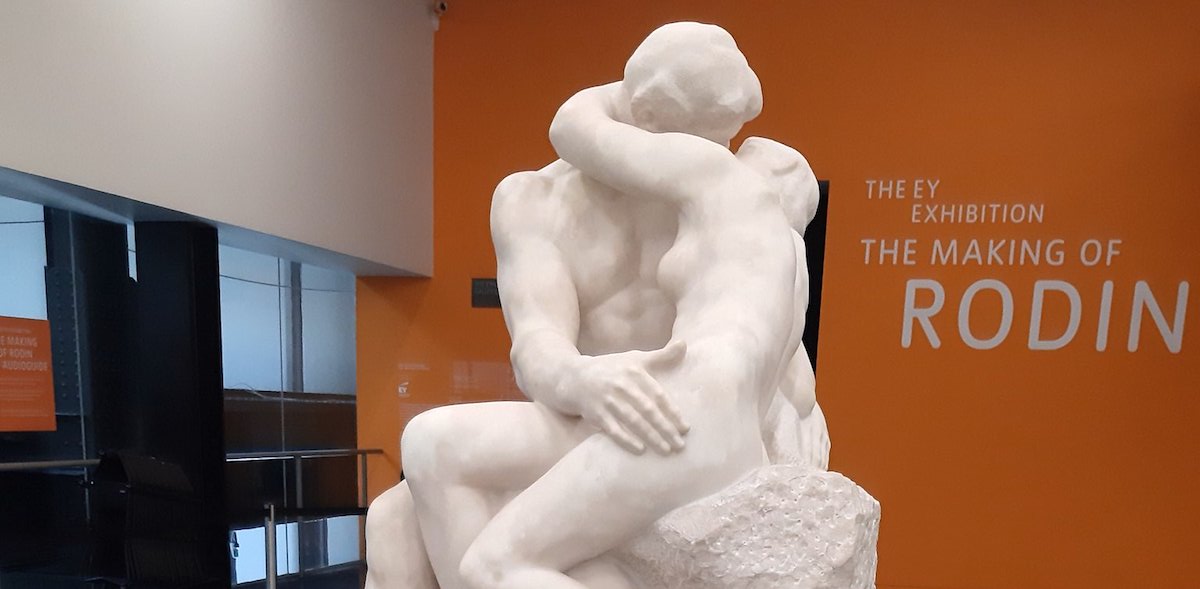

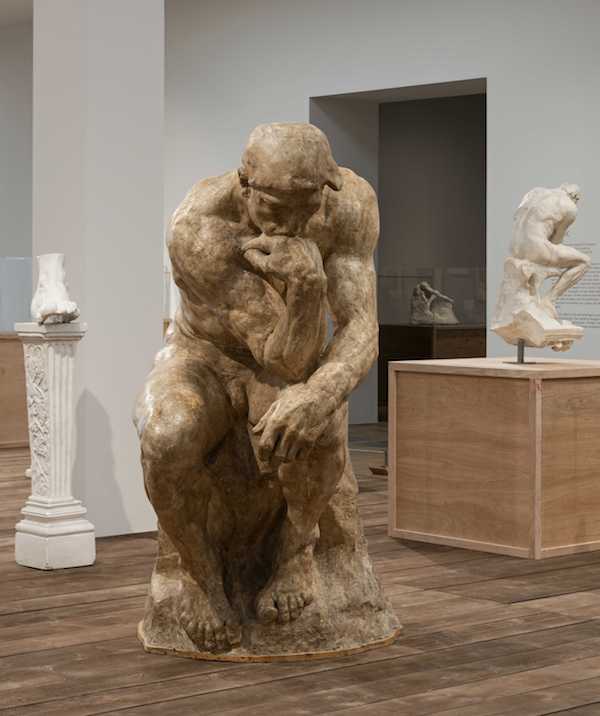

Although the museum for which they were commissioned was never realised, The Gates of Hell became the defining project in Rodin’s oeuvre. Following the award of the commission in 1880, he created over 180 figures and groups on which he then drew for the remainder of his career: enlarging, rearranging, reworking, and recasting these images as independent works. Some of his most well-known works, including The Thinker, The Three Shades, and The Kiss, were originally envisioned as part of The Gates of Hell.

The Thinker was originally located directly above the doors, leaning forward to observe the circles of hell below. Initially titled The Poet and therefore most likely intended as a representation of Dante, the figure reflects on the tragic nature of the human condition, as was Rodin’s own practice with this piece. As with The Three Shades and The Kiss, The Thinker, when extracted from its infernal context, acquires other resonances, yet it is as images of despair inspiring reflection on the torments of the human soul that these images possess the greatest power and come closest to Rodin’s original inspiration and intention.

All are here except for The Gates, which nevertheless haunt the entire exhibition. Rilke wrote that ‘…None of the drama of life remained unexplored by this earnest, concentrated worker… Here [The Gates of Hell] was life, a thousand-fold in every moment, in longing and sorrow, in madness and fear, in loss and gain. Here was desire immeasurable, thirst so great that all the waters of the world dried in it like a single drop…

Suffering was again Rodin’s primary focus when he commemorated the Burghers of Calais. Rather than showing their resolution as they confronted King Edward III and offered their lives in place of their fellow townspeople, he chose to depict their slow, mournful procession to the English camp in which vulnerability and hopelessness is palpable.

Rodin learnt from Michelangelo’s ability to show internal pain and suffering through the gestures of the whole body noting that, ‘It is Michelangelo who has freed me from academic sculpture.’ In describing the greatness of Michelangelo, it was experience of suffering that was emphasised: ‘Michelangelo was only the last and greatest of the Gothics. The turning in of the soul upon itself, suffering, a disgust with life, struggle against the chains of matter, such are the elements of his inspiration … he himself has been tortured by melancholy.’

Rodin also saw suffering and conflict as characteristic of modern art, saying, ‘Nothing is more moving than the maddened beast, dying from unfulfilled desire and asking in vain for grace to quell its passion.’ As Rachel Corbett notes in ‘You Must Change Your Life,’ her biography of Rodin and his secretary, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, to Rodin’ punishment was the condition of the living’ as his vision of Dante’s hell ‘mirrored the realities of life in Paris at the fin de siècle‘ because its inhabitants were ‘living in a nightmare of their own earthly passions.’

Like Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens and G.F. Watts, Rodin had an expansive vision, style and personality whilst being acutely aware of the suffering around him. That was because, as Corbett well describes, leading up to the turn of the century, ‘the population of most European cities doubled, if not tripled.’ This led to ‘descriptions of rapid urbanisation in terms of disease’: ‘The smog-engulfed metropolis became a festering sore, oozing sewage into the rivers, sulfurising the air and breeding bacteria as residents piled on top of each other in apartment complexes.’

After his first work to become well-known, The Age of Bronze, because of the perfection of its realism became subject to accusations that he had made the cast directly from the subject’s body instead of sculpting the figure by hand, Rodin broke with the conventions of classical sculpture and idealised beauty. Instead, he created new images of the human body that reflected the ruptures, complexities, and uncertainties of the modern age through their emphasis on process, materiality, and creative accident rather than perfect finish.

During the making of The Gates of Hell, Rodin built up a collection of individually modelled heads, arms, and legs. Small hands, especially, filled drawer after drawer in his studio. Rodin liked to call them ‘abattis’ (giblets). Rilke wrote of the way the sculptor has ‘made hands, independent, small hands which without forming part of a body are still alive.’

For Rodin, the damaged state of ancient statues seemed to heighten their expressive power and so his work features fragments, assemblages, decapitations, truncations, dismemberments, and amputations. Violence has been done to the majority of the plaster works included in The Making of Rodin. These sculptures are in torment still.

Suffering was the making of Rodin. It was his empathetic depiction of suffering through fragmentation, assemblage and more that broke the rules of classical sculpture and irrevocably changed modern art.

The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, until 21 November 2021